EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated Dec. 19, Dec. 21 and Dec. 22 for new target launch dates.

The demands of launching the first in an upgraded line of U.S. Air Force GPS navigation satellites, including a late load of extra fuel for the spacecraft and a military policy of reserving fuel to eliminate space junk, will keep SpaceX from recovering the first stage of its Falcon 9 rocket following liftoff Sunday from Cape Canaveral, according to mission managers.

The mission set for launch during a 26-minute window opening at 8:51 a.m. EST (1351 GMT) Sunday will mark the first time SpaceX has launched one of its new Falcon 9 “Block 5” boosters in an expendable configuration since the latest Falcon 9 variant debuted in May, with modifications aimed at making the first stage easier to recover and reuse.

But the Falcon 9’s landing capability will not be on display during Sunday’s mission, which is set to blast off from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad.

The rocket’s first stage will fly without the four landing legs and aerodynamic grid fins used to bring the booster back to Earth intact, according to Lee Rosen, SpaceX’s vice president of customer operations and integration. The mission will be the first by SpaceX to dispose of a Falcon 9’s first stage since June, and the first time one of the company’s new Block 5 boosters has ever been intentionally discarded.

SpaceX hoped to launch the Falcon 9 rocket Tuesday — when Vice President Mike Pence was visiting the Florida spaceport — but a bad sensor reading in the final minutes of the countdown forced mission managers to scrub the launch. Officials rescheduled the flight for Thursday, but stormy weather on Florida’s Space Coast kept the rocket grounded. Then upper level winds were a problem during a launch attempt Saturday.

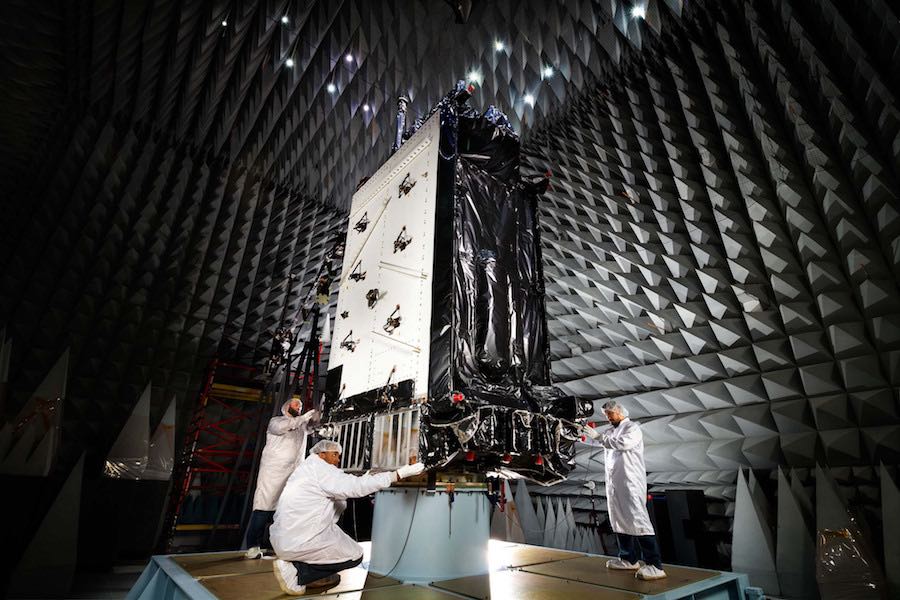

The Falcon 9 rocket is crowned with the Air Force’s first GPS 3-series satellite, the vanguard of a new block of up to 32 Lockheed Martin-built navigation stations with better accuracy and higher power than previous GPS spacecraft. The satellite, valued at more than a half-billion dollars, is heading to an orbit around 12,550 miles (20,200 kilometers) above Earth, with a ground track angled 55 degrees to the equator.

Instead of heading due east from Cape Canaveral, as the Falcon 9 rocket does with most of its commercial communications satellite payloads, the SpaceX launcher will fly to the northeast over the Atlantic Ocean, following a trajectory roughly parallel to the U.S. East Coast. Launching toward the northeast reduces the extra boost in speed a rocket naturally receives from Earth’s eastward rotation, meaning it needs to burn more propellant accelerate the GPS satellite into the proper orbit.

Air Force and SpaceX officials cited those factors, along with the weight of the first GPS 3-series satellite — designated GPS 3 SV01 — and “uncertainty” in the Falcon 9’s performance to such an orbit, as reasons for deciding to forego a landing of the Falcon 9 booster on Sunday’s mission.

The Air Force also has to comply with a government policy instituted in recent years to avoid leaving spent rocket stages in orbit, and the Falcon 9’s upper stage will reignite after releasing the GPS 3 SV01 satellite to target a controlled destructive re-entry back into Earth’s atmosphere a few hours later. Mission designers had to set aside some of the rocket’s fuel for the de-orbit burn to satisfy the Air Force requirement, which is aimed at preventing space junk.

“For this first launch for GPS, we’re given particular parameters in terms of where we have to put them into orbit, as well as what we have in terms of how much weight does the spacecraft have,” said Walter Lauderdale, the GPS 3 SV01 mission director from the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center Launch Enterprise Systems Directorate. “And in doing that mission design to include a re-entry to dispose of the second stage, all those taken together levy performance requirements on the Falcon 9 launch vehicle, (and) as it went through mission design, there simply was not enough performance reserve to meet our requirements and allow them — for this mission — to bring the first stage back, as they’ve been doing quite successfully.”

The first GPS 3-series satellite also weighs more than initially planned after managers opted to load extra fuel into the spacecraft, a move that will give the mission added “resiliency,” said Col. Steve Whitney, director of the Global Positioning Systems Directorate at the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center.

The additional fuel load gives the GPS 3 SV01 spacecraft a launch weight of around 9,700 pounds, or 4,400 kilograms, according to Whitney. That’s more than a half-ton above the satellite’s originally expected weight.

“We added some additional fuel for some mission capabilities to make sure that the system is going to perform,” Whitney said.

The mix of launcher and satellite parameters are the key inputs to designing a rocket mission, and once the Air Force and SpaceX see how the Falcon 9 performs Sunday, engineers could determine if future Falcon 9 launches with GPS satellites will be able to hold enough of a propellant reserve in the booster for a propulsive landing. The Falcon 9’s landing legs and grid fins also add weight to the rocket, reducing the payload it can haul into orbit.

The launch of the GPS 3 SV01 spacecraft is SpaceX’s first national security space mission, a class of U.S. military and intelligence-gathering payloads that include GPS navigation satellites, secure communications satellites, early warning sentinels, and top secret surveillance spacecraft.

SpaceX has launched a handful of missions for U.S. national security customers, including a classified payload for the National Reconnaissance Office and an Air Force X-37B space plane in 2017, but those launches were booked separately from the Air Force’s Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle, or EELV, program. SpaceX’s Falcon rocket family and the Atlas and Delta rocket fleets operated by rival United Launch Alliance are currently certified by the Air Force to compete for EELV-class missions, which include the military’s most costly and highest-priority satellites.

While landing and refurbishing rockets cut costs for future missions, Air Force officials said their concern about the GPS spacecraft outweighed any other considerations.

“Frankly, the rocket is here to make sure we deliver this capability safely and accurately on orbit,” Lauderdale said. “We’ll continue to work with all of our partners to see, as we look at the uncertainty and reduce it, looking for what opportunities are available in the future.”

After getting the Falcon 9 rocket certified for national security launches in 2015, SpaceX won its first GPS 3 launch contract in 2016, an agreement the Air Force said then was valued at $82.7 million. The Air Force has since awarded SpaceX contracts for four additional GPS 3-series satellite launches in head-to-head competitions with ULA, which was the sole company certified to compete for EELV-class launches for a decade.

SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket was certified by the Air Force earlier this year, in the wake of the heavy-lifter’s first test flight in February. The Air Force has already awarded one national security launch contract to the Falcon Heavy since it became eligible for such missions.

“We don’t want to commit to a particular mission,” Lauderdale said in response to a question on whether booster landings could be feasible on future Falcon 9/GPS launches. “Just fundamentally, we need to work through the uncertainty (and) finalize performance. Also, keep in mind, we have Block 5 just introduced this year in May. We’re getting flight experience, together with SpaceX, and that removes uncertainty. That gives us more confidence in what performance the vehicle can deliver, and we’ll continue to work as partners to see what’s possible in the future.”

Lauderdale called the GPS 3 SV01 spacecraft set for launch Sunday “precious cargo.”

“We’re going through and making sure we are taking care of the spacecraft, making sure we meet all of its requirements,” Lauderdale said. “Everything we do, we are making sure that we treat it safely.

“We’re going to see what we actually observed in all the (launch) environments, through all the insertions and the performance of the Falcon 9,” he continued. “We’re going to come back together as a team to refine our analysis and look for opportunities — while we uncompromisingly deliver the spacecraft where it needs to go — and look at if we can get performance back that would enable SpaceX to recover their booster. So it’s an ongoing process.”

ULA’s Delta 4 rocket is slated to launch the second GPS 3-series spacecraft next summer, an Air Force spokesperson said Monday. That is a few months later than the previously-planned launch date in April, a slip industry sources said is due to the Air Force’s preference to complete testing of GPS 3 SV01 in space before committing to launching the second GPS 3 model.

The Delta 4 is an expendable launcher by design, and the launch of the GPS 3 SV02 satellite next year will mark the final flight of the Delta 4’s basic “single stick” configuration. ULA is retiring the smaller variants of the Delta 4 — but keeping the triple-body Delta 4-Heavy in service — and focusing flights in the next few years on the less expensive Atlas 5 rocket, while developing the next-generation Vulcan launcher with reusable Blue Origin BE-4 engines, which could eventually be retrieved and refurbished.

The third GPS 3-series spacecraft is assigned to fly on a Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral in December 2019, the Air Force said. Subsequent GPS launches are planned at intervals of as short as four-and-a-half months, but officials will decide on a launch schedule based on the needs and health of the overall GPS network, according to an Air Force spokesperson.

In total, SpaceX has won contracts to launch five of the first six GPS 3-series satellites on Falcon 9 rockets. Lockheed Martin is under contract to build up to 32 GPS 3 satellites, beginning with a block of 10 spacecraft planned for launch through the early-to-mid-2020s, and followed by a batch of up to 22 follow-on GPS 3F satellites scheduled to launch beginning in 2026.

Air Force officials said some of the GPS satellites could launch on Falcon 9 rockets with previously-flown boosters.

“We absolutely intend to be able to certify previously-flown launch vehicles,” said Col. Robert Bongiovi, director of the Launch Enterprise Systems Directorate at the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center. “We are working with SpaceX to go through and understand what’s different, and what’s better, and what do we have to watch out for when you start going with previously-flown hardware. You’ve got all the return, the checkout and all that stuff. SpaceX has a lot of experience doing this. We learned a lot with them, and we’re trying to put together a plan to actually help us learn as well on doing that, but it’s a process. We’re going to go through and do this in a very deliberate way to make sure the satellite makes orbit on every launch vehicle we procure.”

SpaceX has launched recycled rockets on orbital missions 18 times, all successfully, a tally that includes a pair of previously-flown boosters on the inaugural launch of the Falcon Heavy rocket in February.

GPS launch pushes Falcon 9 to its limits

Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability, told reporters earlier this month that the upcoming GPS launch is a “demanding” mission for the Falcon 9.

Generally, there’s less fuel left over in the Falcon 9 rocket for landing burns on missions aiming for higher orbits, such as geostationary transfer orbit often used for commercial communications satellite launches, or the higher-inclination orbit used by GPS satellites.

On a launch due east from Cape Canaveral into a geostationary transfer orbit stretching more than 22,000 miles above Earth, the Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket — which introduced an uptick in performance in addition to reusability improvements — can loft a payload of more than 14,330 pounds (6,500 kilograms) if SpaceX bypasses a landing opportunity and devotes all of the launcher’s propellant to the payload, Koenigsmann said during an October presentation at the International Astronautical Congress in Bremen, Germany.

Committing some of the Falcon 9’s propellants to landing the first stage on a drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean reduces the rocket’s capacity to the same orbit to roughly 12,125 pounds (5,500 kilograms), Koenigsmann said. The maneuvers required to return the first stage to landing back at Cape Canaveral trim the Falcon 9’s geostationary transfer orbit lift capability to around 7,716 pounds (3,500 kilograms), he said.

While the GPS satellites fly at an altitude below geostationary orbit, their orbits are tilted at a higher angle to the equator, reducing the speed boost offered by Earth’s spin. Factor in the Air Force’s requirement to de-orbit the second stage after the mission, and the GPS launch pushes the Falcon 9 closer to its limits than most flights.

The Air Force has implemented the policy to bring upper stages back into the atmosphere on several recent launches with ULA, resulting in the need to outfit rockets with extra solid rocket boosters, or to place payloads into lower orbits to accommodate the change. Falcon 9 rockets do not carry strap-on boosters, so officials had to make adjustments elsewhere.

A mission timeline released by SpaceX on Monday shows the Falcon 9’s upper stage, powered by a single Merlin engine, will fire two times to inject the GPS 3 SV01 spacecraft into an elliptical transfer orbit, with a high point near the altitude of the GPS satellite fleet more than 12,000 miles above Earth.

Whitney, the Air Force’s GPS directorate director, declined to publicly disclose the exact parameters for the orbit targeted on Sunday’s launch, a break from the service’s policy on previous GPS satellite deployments. SpaceX also has not released the altitude of the target insertion orbit for the GPS 3 SV01 spacecraft. That is consistent with the company’s typical practice, but a departure from the disclosure policies followed by SpaceX’s main competitors.

Separation of the GPS 3 SV01 spacecraft from the Falcon 9 rocket is scheduled at T+plus 1 hour, 56 minutes.

The GPS 3 SV01 spacecraft is set to reach a circular orbit at the GPS fleet’s altitude around 10 days after launch, Whitney said. Seven firings by the satellite’s liquid-fueled main engine are planned to circularize the craft’s orbit.

New GPS satellite will replace 21-year-old navigation craft

Once it joins the rest of the GPS constellation, the new satellite will undergo six-to-nine months of checkouts to verify the health of key spacecraft systems, and test the functionality of its navigation instrumentation provided by Harris Corp. Another testing phase to validate the new GPS satellite’s compatibility with the rest of the navigation network will take an additional six-to-nine months, Whitney said.

When GPS 3 SV01 is ready for operational service, it will replace SVN 43 in Plane F, Slot 6, of the GPS fleet. The Air Force currently operates 31 GPS satellites, including spares, spread among six orbital planes to ensure the network provides uninterrupted global positioning, navigation and timing services to military and civilian users.

SVN 43 has outlived its seven-and-a-half-year design lifetime since its launch as the GPS 2R-2 satellite aboard a Delta 2 rocket in July 1997. The GPS 3 SV01 satellite will be known to GPS users as SVN 74 when it becomes operational, Whitney said.

The Air Force has nicknamed the GPS SV01 satellite “Vespucci” after the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci.

“These GPS 3 satellites will introduce modernized capabilities and signals that are three times more accurate and up to eight times more powerful than previous generations,” Whitney said. “They also broadcast a signal compatible with other global navigation satellite systems, allowing users around the globe the ability ro receive and use the signals from multiple constellations, thus maximizing availability and accuracy of navigation signals worldwide.”

The GPS network currently providers users with position estimates with an accuracy of around 50 centimeters, or about 20 inches, Whitney said, assuming receivers are not contending with terrain, trees, or buildings.

GPS 3’s first launch is four years behind schedule

The Air Force hoped to launch the first GPS 3-series satellite in 2014 when the Pentagon approved full development of the multibillion-dollar program in 2008, according to a Government Accountability Office report.

Officials blamed technical issues with the satellites’ navigation payloads for much of the four-year delay. The navigation payloads consist of ultra-precise rubidium atomic clocks, radiation-hardened processors and powerful L-band transmitters, according to Harris Corp.

The new features on the GPS 3-series satellites include the addition of a fourth civilian L-band signal — known as L1C — designed to be interoperable with other global navigation satellite fleets. Europe’s Galileo, China’s Beidou, and Japan’s QZSS navigation satellite networks provide a similar signal, allowing users to combine navigation fixes with satellites from different fleets, generating a more accurate position estimate.

Just as more satellites give users more accurate position estimates, the stacking of signals at different frequencies allow receivers to sort out distortions caused as the radio waves pass through the upper atmosphere, further refining the accuracy of GPS navigation.

The last satellite in the previous series of Boeing-made GPS spacecraft launched in 2016, and Whitney said the GPS fleet “remains healthy, stable and robust.”

Contributors to the GPS 3 delays included issues with failed and damaged capacitors, components which store and release electrical charges in the satellites’ navigation payloads, according to a GAO report last year.

“According to program officials, each satellite has over 500 capacitors of the same design that experienced failures,” the GAO wrote in a May 2017 report to Congress.

Officials discovered that the subcontractor which supplied the capacitors did not qualify the components for use in the GPS satellites. Engineers then invalidated the results of reliability testing of the parts before the capacitors were finally declared fit for the GPS satellites.

But GPS 3 SV01 is still fitted with the suspect capacitors, according to the GAO.

“The Air Force decided to assume the risk of capacitor failure and proceed with the first satellite as-is, fitted with capacitors mostly from the questionable lot,” the GAO wrote last year. “The program replaced the suspect capacitors in the second and third satellites, the only other satellites that had the suspect parts.”

GPS 3 brings upgrades to global navigation fleet

The GPS 3-series satellites are built to operate at least 15 years, and their higher-power transmitters make their navigation signals less susceptible to jamming.

“The big things here we’re going to see with GPS 3, we’re going to see an increase in power,” Whitney said. “We’ve put a requirement on there to produce stronger signals to try to fight through some of that jamming that we see, particularly on our military signals. We’ve also put on a requirement for increased accuracy. So the user will eventually see that when it comes online. We’ve added some additional civil signals.”

Like the previous line of GPS 2F satellites, the GPS 3-series spacecraft will broadcast a dedicated L5 signal geared to support air navigation. The GPS 3 satellites also continue beaming an encrypted military-grade navigation signal known as M-code.

“GPS 3 satellites will also bring the full capability to use M-code and increase the anti-jam resilience in support of our warfighters and allies,” Whitney said.

The M-code is intended to give U.S. and allied forces an advantage on the battlefield, allowing GPS satellites to beam higher-power, jam-resistant signals to specific regions. It could also give the military the ability to disrupt or jam civilian signals in a particular region without degrading the M-code signals, giving friendly forces an advantage.

“A long time ago, there used to be a capability for what we called then selective availability, where we could degrade, or not put out as accurate of a civil signal,” he said. “That capability no longer exists within the system, but we have gone to this new M-code signal for our military users, which is the same frequency but spectrally separated a little bit. That allows us to do special things for them.”

Even with the first GPS 3 satellite’s launch, all of the upgrades coming in the new generation of navigation satellites will not be available to military and civilian users until developers finish work on a modernized ground control system to make use of the improvements.

Raytheon is charged with developing the Next Generation Operational Control Segment. Better known as OCX, the command and control system is projected to cost up to $6 billion — $2 billion or more over budget — and is at least five years behind schedule. The full version of OCX, known as Block 1, likely won’t be ready until 2021 or 2022, and only then will the full potential of the GPS 3 satellites be realized, Whitney told reporters Dec. 14.

The GAO found that “poor acquisition decisions and a slow recognition of development problems” caused the delays in the new GPS ground command and control system, which is backward-compatible with older GPS satellites and is needed to process the M-code military signal and the new interoperable L1C civilian signal. The Air Force has an initial version of the OCX command and control system — named Block 0 — ready for handle the launch and in-orbit checkout of the GPS 3 satellites, and Whitney said the Air Force is working on an interim upgrade to the existing GPS control system to allow the M-code signal to begin testing with military units in 2020, 15 years after the launch of the first satellite with M-code.

Lawmakers and the GAO have also raised concerns about the readiness of user receivers outfitted to handle the M-code signal, and each new GPS capability will only have global reach when it is deployed on 24 satellites.

“Full M-code capability — which includes both the ability to broadcast a signal via satellites and a ground system and user equipment to receive the signal — will take at least a decade once the services are able to deploy MGUE (military GPS user equipment) receivers in sufficient numbers,” the GAO wrote in a review of the GPS 3 program last year.

Despite the delays and technical hurdles, more users than ever rely on GPS satellites, and the network’s reach extends around the world, infiltrating numerous facets of society and billions of lives, with applications ranging from banking to online dating.

“For the civilian user, GPS has become a pallet on which to create and innovate,” said Johnathon Caldwell, Lockheed Martin’s Vice President of navigation systems. “I don’t think five years ago people thought you’d have your ride-hailing apps, or you’d be able to grab a scooter and get around some of the big cities differently. You wouldn’t see the productivity in America’s heartland without the innovations in farming that have come about.

“The world is changing rapidly,” Caldwell said. “We’re talking about autonomous cars. How can we be more fuel-efficient with airplanes, with automobiles? How can we be better stewards of our environment? GPS, and these new advanced capabilities, give people an opportunity to do creative things and be innovative.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.