A typhoon forecast to move near a ground station in Guam on Monday has forced officials to postpone the launch of a Japanese HTV cargo ship loaded with more than 13,000 pounds of supplies, experiments and a replacement set of batteries for the International Space Station.

Forecasters are monitoring Typhoon Mangkhut as it churns across the Pacific Ocean toward Guam and neighboring islands. A tracking station needed to receive data from the H-2B rocket carrying Japan’s HTV cargo ship into orbit is located in Guam, and officials announced Sunday that the mission would be postponed to wait for the storm to move away from the area.

The launch was scheduled for 6:32 p.m. EDT (2232 GMT) Monday, or 7:32 a.m. Japan Standard Time on Tuesday, and arrival at the space station was expected Friday. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency did not announce a new launch date for the mission — the seventh flight of a Japanese HTV cargo ship to the space station.

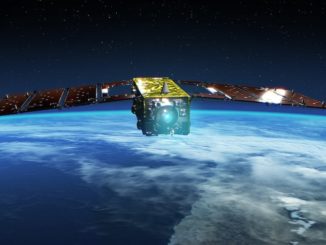

Nicknamed Kounotori 7 — the Japanese word for “white stork” — the spacecraft is mounted atop its H-2B launcher inside the vehicle assembly building at the Tanegashima Space Center. Rollout of the 186-foot-tall (56.6-meter) rocket to its launch pad is scheduled a half-day before liftoff.

JAXA uses HTV missions to pay its share of the space station’s annual operating budget, and it’s the largest of the orbiting research’s labs current fleet of cargo resupply vessels. The HTVs are built by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

The seventh HTV mission will deliver six new lithium-ion batteries to be installed on the space station’s solar power truss, replacing aging nickel-hydrogen batteries used since solar array modules were launched in the 2000s.

The space station has four huge solar power modules, each with solar wings spanning around 240 feet (73 meters) tip-to-tip. Each solar array section powers two electrical channels with 12 charging nickel-hydrogen batteries, and NASA is replacing the old batteries in power truss section with six lighter, more efficient lithium-ion batteries.

The first set of six new batteries launched on the most recent HTV mission in 2016, and two more HTV deliveries in the next few years will finish the battery refresh.

With the help of the station’s robotic handyman Dextre, astronauts will conduct two spacewalks in late September to install the fresh batteries launched in the Kounotori 7 spacecraft’s external payload bay.

Two refrigerator-size Express science racks for NASA are stowed inside the HTV’s pressurized cargo compartment, and an experimental European advanced closed-loop life support system is also riding to the station to demonstrate new air purification and oxygen-generation capabilities that could be used on future deep space missions.

The HTV is also set to carry a new research facility called the Life Sciences Glovebox to the space station. The sealed glovebox, built by JAXA in partnership with the Dutch firm Bradford Engineering, will allow astronauts to work with biological and human physiology experiment samples.

Three Japanese CubeSats are also riding on the HTV supply ship to the space station, where they will be deployed into orbit.

For the first time, Japan is launching a sample return capsule inside the HTV supply ship to test a new re-entry system that could bring back experiment small specimens and other materials from the space station. The test capsule will be released from the HTV at the end of its mission, after departing the station and firing its engines for a deorbit burn.

The HTV is designed to burn up in the atmosphere during re-entry, but the small sample return capsule carries a heat shield to survive the trip back to Earth. The re-entry vehicle is relatively small, measuring 33 inches (84 centimeters) in diameter and 26 inches (66 centimeters) in height, with a weight of less than 400 pounds (180 kilograms), excluding the sample carried inside.

JAXA says the the capsule has an internal volume of about 30 liters, and astronauts could load up to 44 pounds (20 kilograms) of specimens inside.

The re-entry craft will deploy a parachute and splash down in the ocean, where recovery teams will retrieve it and bring it back to Japan for analysis.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.