Running a day late, a United Launch Alliance heavy-lift Delta 4 rocket thundered away from Cape Canaveral early Sunday, boosting NASA’s $1.5 billion Parker Solar Probe into space on a daring seven-year mission to “touch the sun” with repeated trips through the star’s blazing outer atmosphere.

Passing within 3.8 million miles of the sun’s visible surface — well within the shimmering halo of the outer atmosphere, or corona — the spacecraft’s heat shield will endure 2,500-degree heating while whipping past the star at a record 430,000 mph, fast enough to fly from New York to Tokyo in less than a minute.

The goal is to help scientists figure out what makes the corona hotter than the sun’s visible surface and what accelerates charged particles to enormous velocities, producing the solar wind that streams away from the corona in all directions.

And the mystery is profound. The visible surface of the sun has a temperature of about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit. But just above it, in the corona, the temperature shoots up to several million degrees.

Even though it will repeatedly fly through the corona, Parker will not experience such extreme temperatures because the ionized gas making up the outer atmosphere is so tenuous. But the probe’s heat shield will still get hotter than lava while its instruments study the hellish environment in unprecedented detail.

Scientists have two theories about what heats up the corona. It could be due to interactions between electrically charged particles and the sun’s powerful magnetic field, or it could be the result of countless “nanoflares” governed by another mechanism. Or maybe, both.

“Until you actually go there and touch the sun, you really can’t answer these questions,” said Project Scientist Nicola Fox. “Why is the corona hotter than the surface of the sun? That defies the laws of nature. It’s like water flowing uphill, it shouldn’t happen.

“Why in this region does the solar atmosphere suddenly get so energized that it escapes from the (gravitational) hold of the sun and bathes all of the planets? We have not been able to answer these questions.”

Learning more about the solar wind also will help scientists better predict the effects of solar storms and the impact of the solar wind on Earth’s magnetic field, wreaking havoc with communications, power grids and navigation.

“This space weather has direct influence, not always positive, on our technology in space, our spacecraft, it disrupts our communications, it creates a hazardous environment for astronauts and in the most extreme cases can actually affect our power grids here on the Earth,” said Alex Young, associate director of NASA’s heliophysics program.

“So it’s of fundamental importance for us to be able to predict this space weather much like we predict weather here on Earth.”

To reach its target, the Delta 4 Heavy and a solid-propellant upper stage had to supply enough energy to counteract Earth’s 18-mile-per-second orbital velocity around the sun, allowing the spacecraft to fall into the inner solar system.

Running 24 hours late because of a last-minute countdown glitch Saturday, the trek began at 3:31 a.m. EDT (GMT-4) Sunday when the 233-foot-tall Delta’s three hydrogen-fueled Aerojet-Rocketdyne RS-68A main engines ignited with a rush of brilliant orange flame and quickly throttled up to 2.1 million pounds of thrust.

Looking on at launch was Eugene Parker, the University of Chicago astrophysicist who first theorized the existence of the solar wind in 1958. Now 91, Parker, the first living scientist to have a space probe named in his honor, flew to Cape Canaveral to witness his first rocket launch.

The Delta 4 Heavy did not disappoint.

“I really have to turn from biting my nails and getting it launched to thinking about all the interesting things, which I don’t know yet, and which will be made clear, I assume, over the next five or six or seven years,” Parker said in a NASA interview.

“It’s a whole new phase, and it’s going to be fascinating throughout. … All I can say is wow, here we go. We’re in for some learning over the next several years.”

Trailing a plume of fiery exhaust visible for scores of miles around, the huge 1.6-million-pound rocket majestically climbed away from launch complex 37B at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, arcing away on an easterly trajectory over the Atlantic Ocean.

The rocket smoothly accelerated as it consumed propellant and lost weight, powering out of the thick lower atmosphere in spectacular fashion. The two side boosters shut down and fell away as expected a bit less than four minutes after liftoff.

The central core booster continued firing for another minute and a half before it, too, shut down and fell away from the fast-moving second stage. A few seconds after that, the upper stage’s single hydrogen-fueled Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10B-2 engine ignited to continue the climb to space.

Finally, after two firings of the second-stage engine, the Parker Solar Probe and its Northrup Grumman solid-fuel upper stage were released from the Delta 4. The upper stage then ignited for a short burn, supplying more than half of the probe’s final velocity.

Forty-three minutes after launch, the spacecraft jettisoned the spent upper stage and began flying on its own.

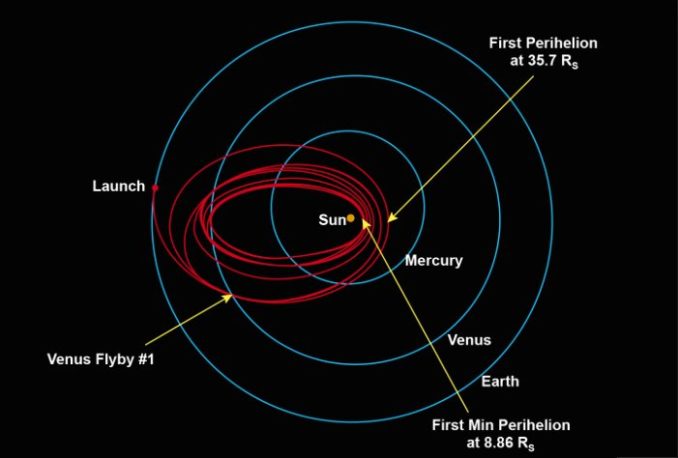

If all goes well, the Parker Solar Probe will swing by Venus in about six weeks for a gravitational encounter that will help the spacecraft slow down still more. Seven Venus flybys are planned over the seven-year mission to fine-tune the trajectory, setting up the close-in aim points.

The first pass by the sun, at a distance of about 15 million miles — three times closer than any previous spacecraft — is expected in November.

“So we’re already in a region of very, very interesting coronal area,” Fox said. “In fact, one of the key things about our early orbits is we’re actually just at this sort of sweet spot … over the same area of the sun for many, many days, allowing us to do some really incredible science on our very first flyby.”