Engineers are studying a malfunction with the main imaging instrument on NOAA’s GOES-17 weather satellite, launched March 1, that could limit the observatory’s ability to monitor storms, winds and other weather phenomena at night, officials said Wednesday.

A cooling system aboard the satellite is unable to chill infrared detectors inside the Advanced Baseline Imager on GOES-17 to proper temperatures, degrading the camera’s performance.

The imager is designed to be sensitive to light in 16 channels, including 13 infrared and near-infrared wavelengths, and three colors in the visible spectrum. The thermal control anomaly currently under investigation affects the 13 infrared and near-infrared channels, according to Steve Volz, assistant administrator for NOAA’s satellite and information service.

“This is a serious problem,” Volz said Wednesday in a conference call with reporters. “This is the premier Earth-pointing instrument on the GOES platform, and 16 channels, of which 13 are infrared or near-infrared, are important elements of our observing requirements, and if they are not functioning fully, it is a loss. It is a performance issue we have to address.”

Detectors for the infrared channels must be cooled to around 60 Kelvin (minus 351 degrees Fahrenheit) to make them fully sensitive to infrared light coming from Earth’s atmosphere. For about 12 hours each day, the cooler inside the Advanced Baseline Imager, or ABI, is unable to chill the detectors to such cold temperatures, officials said.

Infrared images from weather satellites are used to monitor storms at night, when darkness renders visible imagery unavailable. The three visible channels from the ABI are not affected by the cooling problem.

“The other wavelengths, the near-infrared and infrared wavelengths — the other 13 — need to be cooled to some extent beyond the capability of the system at present,” said Tim Walsh, NOAA’s program manager for the GOES-R weather satellite series. “There’s a portion of the day centered around satellite local midnight where the data is not usable, and that’s what we’re addressing.”

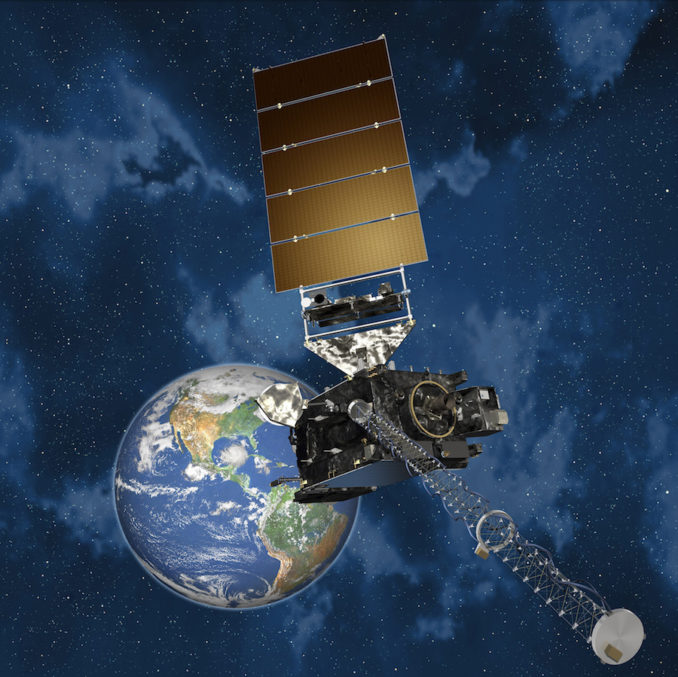

GOES-17 is parked in geostationary orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator, where the satellite circles Earth at the same rate of the planet’s rotation, giving its instruments a fixed field-of-view. Since its launch March 1 from Cape Canaveral atop an Atlas 5 rocket, GOES-17 has activated its other sensors, including a lightning detector and space weather payloads, without any problems to begin a planned six-month test campaign.

But the ABI is the centerpiece instrument on GOES-17.

Designed and built by Harris Corp. in Fort Wayne, Indiana, the imager is intended to provide satellite imagery of clouds, cyclones, storm fronts, fog, wildfires and other phenomena for use by forecasters. It’s the same imagery that is regularly broadcast on television weather reports.

An identical satellite named GOES-16 launched in November 2016, and it entered service late last year after a thorough checkout. GOES-16, known as GOES-R before launch, was the first if four modernized weather satellites developed in an $11 billion program by NOAA.

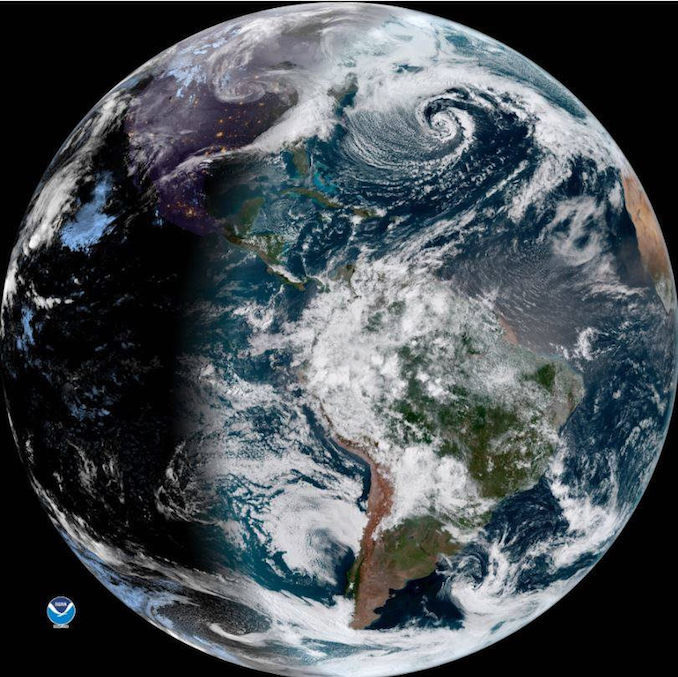

GOES-16 covers the eastern United States, the Atlantic Ocean and South America, with coverage extending to West Africa to track low pressure systems that could form tropical storms and hurricanes. The launch of GOES-17, previously named GOES-S, followed in March, and NOAA said the new satellite would begin observations by the end of the year to provide coverage over the western United States, including Alaska and Hawaii, and the Pacific Ocean extending to New Zealand.

Joe Pica, director of operations at NOAA’s National Weather Service, said meteorologists also feed infrared data from GOES satellites into numerical weather prediction models, providing upper level and mid-level wind inputs and water vapor measurements to help improve the accuracy of forecasters. Those infrared observations are required not just at night, but all day.

“If efforts to restore the cooling system are not successful, we are looking at alternative concepts and different modes to maximize the operational utility of this ABI for NOAA’s National Weather Service and other customers going forward,” Volz said.

NOAA’s GOES-15 weather satellite, launched in 2010, is currently operating in the “GOES-West” location where GOES-17 was destined. The weather agency also has a backup spacecraft, the nearly nine-year-old GOES-14 satellite, in standby mode, ready to take over if one of the operational observatories fails.

“We have two spacecraft that we could use to augment whatever we do in the GOES-West area,” Walsh said.

“Our delivery of services is not impacted,” Volz said. “It’s our future capability that we would have enhanced by the extra performance of GOES-17 to be delivered in the coming year that is on the table right now for discussion.”

The Advanced Baseline Imager carried on NOAA’s new generation of GOES weather satellites can capture more vivid views of storms than cameras aboard older weather craft, and record images quicker.

The ABI can return scans of an entire hemisphere once every 15 minutes, half the time needed by one of NOAA’s earlier geostationary spacecraft. The imager can scan the continental United States once every 5 minutes.

The new ABI-equipped satellites can return pictures of hotspots like hurricanes at a cadence of once every 30 seconds, an improvement from the five-minute rapid scans available today. The imager can simultaneously scan the broader hemisphere in its field-of-view and capture close-up views of individual storm systems, giving forecasters refreshed views of hurricanes and tornado outbreaks.

The 16-channel ABI can yield deeper insights into moisture levels and cloud types unavailable with previous weather satellite images. Earlier GOES satellites had imagers sensitive to five different parts of the light spectrum.

The upgrade allows meteorologists to distinguish between snow, fog, clouds, volcanic ash, and other particles suspended in the atmosphere.

Engineers continue investigating the cause of the cooling system malfunction inside GOES-17’s imager, and officials remained hopeful Wednesday that the problem could be corrected, or at least mitigated.

“We’re treating this very seriously with a multi-agency and contractor technical team to try and undertand the anomaly and find ways to start the engine, if you will, of the cooling system to function properly,” Volz said. “Doing this remotely from 22,000 miles below, only looking at the on-orbit data, is a challenge,” Volz said.

“What we’re seeing on (GOES) 17 is that we can only achieve that (60 Kelvin) operating temperature about half of the day … Over the couse of the orbit, we see different thermal conditions, different sun conditions that change how hot the instrument gets,” said Pam Sullivan, GOES-R flight project manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “During the hot part of the orbit, the thermal load increases to the point that we’re not able to cool the detectors down.”

The instrument is hottest while the satellite is over the night side of Earth because the sun is positioned off the limb of the planet, and shining in the camera’s aperture.

The cooler is supposed to transfer heat from the instrument and discharge it to space via a heat pipe and a radiator. The thermal system works by cycling a fluid named propylene between the ABI instrument and the radiator. Engineers think they have narrowed the problem to the heat pipe/radiator system.

“The problem is that the cryocooler, the mechanical cooler, is overheating because the heat pipes that transport heat from the cryocooler to the external radiator, that heat pipe/radiator system does not seem to be working as intended right now,” Sullivan said.

Investigators are examining the performance from the identical imager on GOES-16, as well as similar imagers on Japan’s Himawari 8 and 9 weather satellites, which were also built by Harris and are working normally.

“It is deflating when you want see just exactly the same thing we saw before, given the dramatic success that GOES-16 was, as well as Himawari 8 and 9,” Volz said. “We expected the same performance, and we still hope for that, but it is a little bit upsetting to see this happen.”

“People have dug in, we’re not even close to out of ideas,” Sullivan said. “There are lots of lines of inquiry of things that could be the problem and lots of ideas about things to try to address those, and also a lot of work about what can we do to improve the situation, even if the thermal performance doesn’t improve.”

Even if engineers are unable to get the cooling system to full functionality, Volz said GOES-17’s imager would still be “partially usable.”

“The worst-case scenario does not mean we don’t have any channels in infrared,” Volz said. “We are getting degraded performance on the infrared and near-infrared channels, not zero performance but degraded.”

“We’re trying to assess what exactly the performance is, and the visible (channels) are working quite well,” he said. “We still have a highly capable functioning spacecraft and mission, even under the current operating conditions that we’re seeing in the initial test period.”

But reduced performance could prevent forecasters from relying on the satellite as the primary weather sentinel over a broad segment of the United States and neighboring waters.

“Whether we fix it completely or we do not fix it completely, how do we maximize the mission? I think that’s where the team is focusing right now,” Walsh said.

NOAA has two more GOES satellites — GOES-T and GOES-U — set for launch in the coming years. They will host the same type of Advanced Baseline Imager as GOES-17.

Volz said it was too early to say whether NOAA could move up the GOES-T launch date to replace the observing capacity that GOES-17 was expected to fill.

GOES-T is set for launch in May 2020, followed by GOES-U in 2024. NASA, which oversees the launch of NOAA weather satellites, has not selected launch provider for either mission, but United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 rocket and SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launcher are expected to compete for the contracts.

The four new-generation GOES spacecraft are manufactured by Lockheed Martin.

“The first thing we need to understand the anomaly and whether or not it affects the other elements, the GOES-T and U spacecraft and missions, because those ABIs are complete and are in our hands,” Volz said.

“We have not defined new launch dates. There are some things you can’t move up too much. We have prepared GOES-T for a 2020 launch, and at this point it’s premature to say where or how we would change that launch date.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.