A pair of European-built, NASA-backed research satellites set for launch Tuesday from California will extend 15 years of global gravity field measurements collected by the GRACE mission before it ended last year, supplying scientists with data to help track the melting of Earth’s ice sheets and chart the impacts of floods and droughts.

The two new satellites were built as a follow-up to the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, which used two similar spacecraft to measure the tug of gravity around the world from 2002 through 2017.

“GRACE and GRACE-Follow On are some of NASA’s most unique missions,” said Michael Watkins, GRACE-Follow On science lead and director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “What GRACE has done, and what GRACE-Follow On will do shortly after its launch, is map the Earth’s water in motion.

“What’s fascinating about GRACE is it does it not by looking the surface of Earth — not by looking at water or by bouncing a radar off the water — but by actually measuring the weight of the water,” Watkins said. “So it actually is able to tell how much water is in a given location on the Earth and how that’s changing over time.”

The GRACE-Follow On research craft will ride into orbit Tuesday from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, along with five Iridium communications satellites.

Liftoff from Space Launch Complex 4-East at Vandenberg, a military base around 140 miles (225 kilometers) northwest of Los Angeles, is scheduled for 12:47 p.m. PDT (3:47 p.m. EDT; 1947 GMT).

On Tuesday’s mission, the Falcon 9 rocket is set to deliver the Iridium and GRACE-Follow On payloads to two different orbits, utilizing two firings of the upper stage’s Merlin engine.

The GRACE-Follow On satellites will deploy first from the Falcon 9 rocket around 11 minutes after liftoff in an orbit around 304 miles (490 kilometers) above Earth inclined at an angle of 89 degrees to the equator, a track that will take the twin spacecraft almost directly over the poles on each lap around the planet.

A brief restart of the upper stage engine is planned approximately 57 seconds after liftoff to reach a slightly higher orbit around 373 miles (600 kilometers) in altitude, followed by release of the five Iridium Next satellites one-at-a-time.

The Iridium satellites will join the company’s network of voice and data relay stations. Iridium’s fleet is being replaced with new-generation satellites offering the company’s one million subscribers improved service, and the upgraded constellation will have 55 spacecraft in orbit with Tuesday’s launch, with 20 more satellites set to go into space in the next few months.

SpaceX’s launch team conducted a pre-launch hold-down firing of the Falcon 9 rocket Friday at Vandenberg, then returned the launcher to a nearby hangar, where ground crews mated the Iridium and GRACE-Follow On satellites.

SpaceX does not plan to recover the first stage booster on Tuesday’s mission, but the company could attempt to retrieve part of the Falcon 9’s payload shroud, which shields the satellites during liftoff, then is designed to descend back to Earth with the aid of a parafoil and steering thrusters.

SpaceX’s fast-moving boat fitted with a net to catch the fairing has been dispatched from the Port of Los Angeles, presumably toward the downrange zone where the fairing is projected to fall.

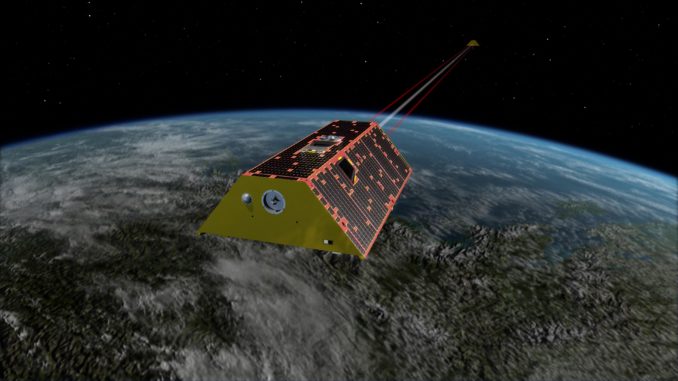

Built by Airbus Defense and Space, the identical GRACE-Follow On satellites carry microwave ranging instruments to measure the separation between the craft as they fly around 137 miles (220 kilometers) apart in orbit.

“Think of the actual satellite size as about the size of a sports car, one in Los Angeles and one in San Diego,” said Phil Morton, NASA’s GRACE-Follow On project manager at JPL. “That’s about how far apart they’re flying typically.”

The ranging sensors require exacting precision, with the capability of measuring distance changes between the formation-flying satellites as small as a few microns — about the width of a blood cell.

Changes in the range between the two GRACE-Follow On satellite will be caused by tiny variations in the pull of gravity from Earth below, telling scientists about the mass of water, rock and ice around the world.

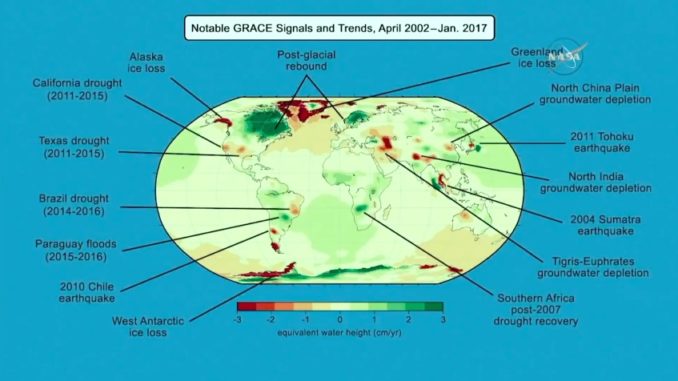

The 15-year GRACE mission ended last year, and both satellites have re-entered Earth’s atmosphere and burned up after outliving their originally planned five-year lifetimes. They provided the most detailed measurements of how much ice is melting in Greenland and Antarctica, and they monitored how extreme events like floods and droughts — and normal seasonal changes — affected the water table and aquifers on Earth’s land masses.

“Water takes many different forms,” Watkins said. “Sometimes it’s in the form of ground water deep underground, sometimes it’s in the form of polar ice gaps, sometimes it can be in the form of ocean water moving around.

“GRACE observed all of that complete water cycle of the Earth, and how it changes over time … We have 15 years of GRACE data, and what GRACE has shown is there are significant changes in each part of the world, and how much water is stored in each part of the world.”

Frank Webb, GRACE-Follow On project scientist at JPL, said the GRACE mission showed Greenland has been losing 281 gigatons of ice per year. A gigaton is roughly equivalent to a cubic kilometer of water, Webb said.

In Antarctica, ice is melting at an overall average rate of about 120 gigatons per year, with some parts of the continent losing more ice and other regions adding ice.

From the ice loss in Greenland and Antarctica alone, sea levels are rising by about a millimeter per year, Webb said. Other drivers cause the mean sea level to rise more.

“I think the rate at which the polar caps were losing mass was something that was a little surpring to folks,” Watkins said. “When we launched GRACE (in 2002), it wasn’t clear how fast the polar sheets were changing. I think GRACE gave the first clear picture of what’s going on, and that’s been followed up with other more precise measurements for local areas like with radar or the upcoming ICESat 2 mission.”

The GRACE-Follow On satellites each weigh around 1,300 pounds, or 600 kilograms, and are sized and shaped the same as the original GRACE spacecraft, ensuring they collect the same types of data.

But engineers added upgrades to the new satellites, including laser ranging devices that the GRACE-Follow On mission will demonstrate in space. The lasers could be capable of measuring the distance between the satellites with a precision 10 times better than the baseline microwave instrument, according to Frank Flechtner, GRACE-Follow On project manager at GFZ in Potsdam, Germany.

The GRACE-Follow On satellites also carry instruments to signals from GPS navigation satellites that pass through the atmosphere on Earth’s horizon — as seen from orbit. Scientists can analyze how atmospheric particles altered the GPS radio signal, and use that information to derive estimates of atmospheric temperature and humidity at high altitudes.

But the $520 million mission’s prime research objective is focused on gravity measurements and Earth’s water cycle.

“The satellites are sensitive to all mass change around the globe,” Webb said. “We make measurements every 30 days, so we see atmospheric, ocean tides, solid earth changes, water ice moving around.”

Like their predecessors, the new GRACE satellites are designed for five-year lifetimes, but they could last much longer. The additional data will help scientists “understand if these trends are just short-term variability, or longer trends related to our evolving climate,” Webb said.

For example, the original GRACE satellites detected a depletion of water from an aquifer under California during a long-term drought.

“At the end of the GRACE time series, we had a large rainstorm, and there was some recovery in the amount of mass — the amount of water in the ground,” Webb said Monday. “And it remains to be seen, since GRACE ended in 2017, how that recovery goes forward. Once GRACE (Follow-On) launches tomorrow, we’ll start getting data, and we’ll have about a one-year gap, and we’ll be able to see how much of that water that fell in precipitation in California actually stayed in the ground and went into storage, and how much actually ran off and went into the ocean.”

Information about the health and capacity of aquifers will help policymakers, farmers and environmental scientists work together to better manage resources, Webb said.

The GRACE-Follow On satellites were supposed to launch on a Dnepr rocket from Russia last year, but the Russian government decided to discontinue the Dnepr program — managed by a Russian-Ukrainian company called Kosmotras — after relations deteriorated with Ukraine, where the launcher was manufactured.

The selection of a rocket was the responsibility of GRACE-Follow On’s German team, and GFZ arranged for another launch opportunity with Iridium and SpaceX when it was clear the original Dnepr launch contract would not be fulfilled.

Iridium already had a contract with SpaceX for seven Falcon 9 flights, each with 10 Iridium satellites on-board, to build out the company’s new-generation telecom network. Iridium agreed to reserve an eighth launch in a rideshare arrangement with GFZ, carrying just five Iridium satellites to account for the extra capacity needed by the two GRACE Foll0w-On spacecraft.

Iridium also had planned two launch its first two new-generation satellites on a Dnepr rocket, but like in GRACE Follow-On’s case, that agreement was blocked by the cancellation of the Dnepr program.

“We were thinking we’d use the Dnepr rocket for two, and when that wasn’t going to work out because the Russians weren’t going to fly it, we still wanted to launch a few more satellites,” said Matt Desch, Iridium’s CEO, in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “Talking to SpaceX and asking what they would recommend … they pointed us initially toward GRACE because GRACE also had been looking for a ride.

“So we took the lead on it,” Desch said. “We thought that this would make a lot of sense. We reached out to GRACE directly, we started talking to people at JPL, GFZ, and started talking about the details of it. We contracted with SpaceX, and then we kind of subcontracted with GRACE to use half the payload capacity, and started working out the technical details well over a year ago.”

The marriage of the Iridium satellites, built by a partnership of Thales Alenia Space and Orbital ATK, and the Airbus-based GRACE Follow-On satellites, with a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket was a good example of global cooperation between parties which are sometimes competitors, Desch said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.