STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

Vice President Mike Pence, chairing a revived National Space Council, said Thursday the United States will once again send astronauts to the moon, using Earth’s satellite as a critical stepping stone for eventual flights to Mars, and vowing to beef up national security space assets to counter rapidly escalating threats from adversaries.

In the human spaceflight arena, Pence said the Trump administration’s space policy calls for sending missions to the moon to test new technologies, to establish infrastructure far beyond low-Earth orbit and to serve as a staging base on the surface, or a gateway in lunar orbit, for robotic and human flights to Mars.

Experts told the panel NASA could return astronauts to the moon within five years using the agency’s huge Space Launch System rocket and Orion crew capsule — and possibly a Saturn 5-class rocket envisioned by SpaceX — to lay the groundwork for landings on the lunar surface or developing an orbital outpost.

“The president has charged us with laying the foundation for America to maintain a constant commercial human presence in low-Earth orbit,” Pence said, standing in front of the space shuttle Discovery at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center.

“From there, we will turn our attention back toward our celestial neighbors. We will return American astronauts to the moon, not only to leave behind footprints and flags but to build the foundation we need to send Americans to Mars and beyond.”‘

He said the moon would serve “as a stepping stone, a training ground, a venue to strengthen our commercial and international partnerships as we refocus America’s space program toward human space exploration. And under President Trump, this council will spur the development of space technology to protect America’s national security.”

Pence said Russia and China are pursuing “a full range of anti-satellite technology to reduce U.S. military effectiveness, and they’re increasingly considering attacks against satellite systems as part of their future warfare doctrine.”

“Our adversaries are aggressively developing jamming, hacking and other technologies intended to cripple military surveillance, navigation, communications systems,” he said. “In the face of these actions, Americans must be as dominant in space as we are here on Earth.”

Former NASA Administrator Mike Griffin agreed, telling the panel the nation needs to quickly improve its ability to identify realtime threats in space, to protect current national security space assets and to clearly state a policy that considers attacks on critical space infrastructure an attack on the United States.

“Our space infrastructure has been, is being and will continue to be targeted by those who seek to alter the global order while blunting our opposition to that,” Griffin told the space council. “Our adversaries can already, and are increasing, their ability to project their power into space.

“While we must develop defenses against such actions, defense by itself will always be insufficient,” he said. “Defense must succeed every time, the adversary must succeed only once. Accordingly, we must develop our own capabilities to project power in space. We must be able to hold adversaries’ space capabilities at risk even as they seek to do so to ours.”

In an op-ed piece in Thursday’s Wall Street Journal, Pence said the long-dormant National Space Council, re-activated by President Trump, will establish a “Users’ Advisory Group” drawn from the private sector to leverage new technologies and innovation.

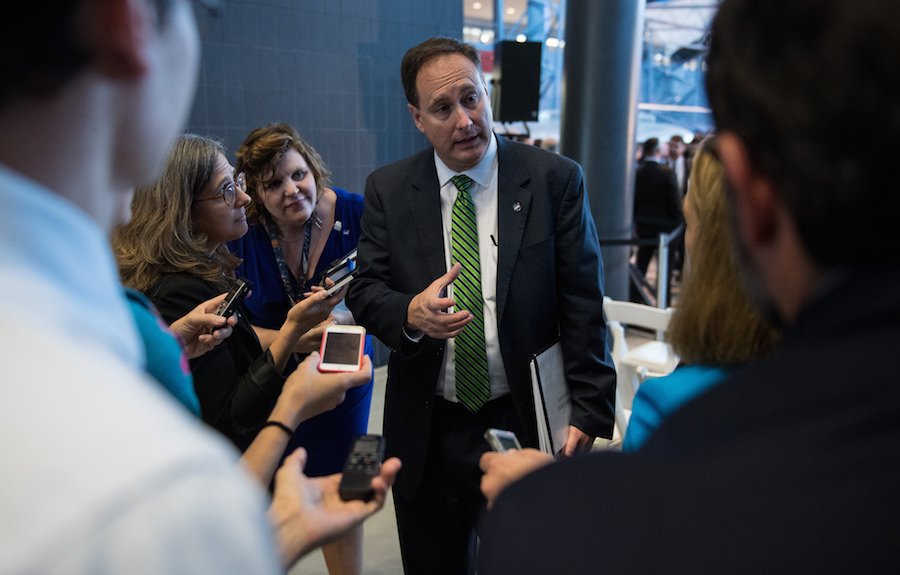

Pence was joined Thursday by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, acting NASA Administrator Robert Lightfoot and other senior administration officials including Office of Management and Budget Director Mike Mulvaney and National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster.

Three panels of experts were invited to discuss civil space policy, commercial space and national security.

Representing civil space were Lockheed Martin President and CEO Marilyn Hewson, Dennis Muilenburg, president and CEO of Boeing, and David Thompson, president and CEO of Orbital ATK. All three agreed Americans could return to the moon within five years given funding and political support. And all three said steady, long-term funding was essential.

“From a policy standpoint, if we look at the national budget, year-to-year stability and alternatives to the budget cap approach that we have in place today, sequestration, we need an alternative,” Muilenburg said. “That’s good for the U.S. government, it’s good for the economy, it’s good for industry so we can do long-term planning together.

“Without that long-term view and long-term stability in funding, it’s difficult to build a supply chain, it’s difficult to make the investments for long-term space infrastructure. I think that’s one of the most important things we can do as a country.”

Hewson agreed, saying “that is a message to you as a space council, that we really do need to make sure we have stable funding, that we have aspirational programs we’re investing in so we can continue to be a leader in space.”

The commercial space panel included Gwynne Shotwell, president and chief operating officer of SpaceX, Bob Smith, CEO of Blue Origin, founded by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, and Fatih Ozmen, CEO of Sierra Nevada.

Shotwell and Smith agreed that reusable rockets are key to making space exploration affordable. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rockets already are partially reusable and Blue Origin plans a family of reusable boosters as well.

All three commercial space representatives agreed human flights to the moon can be mounted in the near term with sustained government support. Shotwell said SpaceX’s “BFR” super rocket, a design unveiled last week by company founder Elon Musk, could eventually carry hundreds of people into orbit, to the moon and eventually, Mars.

Shotwell called for expanded, more efficient public-private partnerships to speed development of new systems and modernization of rules to reduce red tape and speed launch approval in an era of reusable rockets. Pence said he hopes to have suggestions for regulation revision ready for review the next time the space council meets.

Joining Griffin on the national security panel were retired Adm. James Ellis, former commander of U.S. Strategic Command, and former shuttle commander Pamela Melroy, deputy director of the Tactical Technology Office at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

All three said space assets are critical to both the national economy and defense and that adversaries were rapidly developing threats to that infrastructure that must be quickly countered.

“Civil, commercial and national security space are all inextricably linked together,” said Melroy. “When you stop and think about the number of ATM transactions that go through comercial geo satellites today and ask yourself about critical infrastructure, you begin to see it’s not just a launch pad or other types of capabilities that are in that critical path.”

Griffin said if that infrastructure was lost or seriously damaged, “our national security communications would be greatly reduced.”

“I don’t think the general public realizes the extent to which the (Global Positioning System’s) timing signal is critical for these ATM transactions and every other point-of-sale transaction conducted in the United States and most of the world.

“I have to ask the question, to what extent do we believe we have defended ourselves if an adversary can bring our economic system near collapse? We may not lose a single piece of hardware, but we’re not functioning as a nation.”

Griffin said the United States must “make it clear that we will protect our space assets, that we do not allow our adversaries an unfettered field of force application in space, that we choose not to be the first, but we will assuredly be the last.”

A return to the moon would mark the third major shift in U.S. national policy governing human exploration since the turn of the century.

At the time of the Columbia disaster in February 2003, NASA was planning to fly the shuttle through 2020 in support of the International Space Station. But the presidential commission that investigated the mishap recommended that NASA carry out a detailed — and costly — engineering review if the agency wanted to operate the shuttle past 2010.

The following January, the Bush administration ordered a radical change of course. NASA was directed to finish the International Space Station and retire the shuttle by the end of the decade and to focus instead on building new rockets and spacecraft for a return to the moon in the early 2020s. Antarctica-style moon bases were envisioned as both a science initiative and as stepping stones to eventual flights to Mars.

To carry out that directive, NASA, under Griffin’s leadership, came up with the Constellation program and began designing a new Saturn 5-class rocket to boost lunar modules and habitats to the moon, along with a smaller rocket to carry astronauts to and from low-Earth orbit.

The crew capsule was called Orion and the plan was to link up with the lunar lander/habitat in Earth orbit and then head for the moon. The astronauts would descend to the surface in a lander/habitat, stay for several weeks or months and then blast off to rendezvous with Orion, which would carry the crew back to Earth.

During the initial development of the Constellation program, NASA pressed Congress for the funding to get the new rockets flying as soon as possible to minimize the gap between the end of shuttle operations and the debut of a new spacecraft.

NASA originally thought that gap would be about two years, during which the agency would have to pay Russia to ferry U.S. astronauts to and from the space station. As it has turned out, that gap will now extend into 2018 and possibly longer.

During the 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama generally supported Constellation but after the election, he ordered a review. A presidential panel ultimately concluded Constellation was over budget and unsustainable, suggesting instead that NASA adopt a “flexible path” architecture, bypassing the moon in favor of a manned flight to an asteroid and an eventual flight to orbit Mars.

The Obama administration ultimately approved a two-tiered approach to human spaceflight. It retained the Constellation program’s Orion capsule, built by Lockheed Martin, and ordered NASA to build a single large rocket, what became the Space Launch System, for deep space exploration.

The long-range goals called for visiting an asteroid in the mid 2020s and a flight to at least orbit Mars in the mid 2030s.

The Obama administration later specified an asteroid retrieval mission to robotically haul a small asteroid, or part of one, back to the vicinity of the moon for hands-on exploration by astronauts aboard an Orion spacecraft. Such missions would set the stage for an Orion, attached to a habitation module of some sort, to make an eventual flight to orbit Mars or its moons.

The asteroid capture mission never generated widespread support and the Trump administration canceled funding in its proposed budget.

But the administration supports the continued development of commercially provided crewed spacecraft to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station, thus ending NASA’s reliance on the Russians.

On Sept. 16, 2014, NASA announced that Boeing and SpaceX would share $6.8 billion to develop independent space taxis, the first new U.S. crewed spacecraft since the shuttle.

SpaceX, under a $2.6 billion contract, is building a crewed version of its Dragon cargo ship that would ride into orbit atop the company’s Falcon 9 rocket. Boeing is designing its own capsule under a $4.2 billion contract that would launch atop United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rockets.

Both spacecraft will carry four-person crews to the space station and both companies also are exploring possible non-station commercial use.

The commercial crew ships are scheduled for initial unpiloted and piloted space flights next year, although agency insiders say some or al of the flights could slip into 2019. First flight of the Space Launch System rocket, an unpiloted test flight, is planned for 2019. The first flight of the SLS with astronauts on board is expected in the 2022 timeframe.