Two days after launching a Falcon 9 rocket from Florida, SpaceX sent another mission into orbit Sunday from California’s Central Coast with 10 new satellites for Iridium’s voice and data relay network.

Like Friday’s flight from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the Falcon 9’s first stage plunged back through the atmosphere and made a propulsive vertical landing on a barge stationed several hundred miles downrange from the launch site.

The back-to-back launchings and landings set a record for the shortest turnaround between two SpaceX flights from different launch sites, a milestone the company could repeat as it reactivates a damaged launch pad at Cape Canaveral later this year and begins service from a Texas spaceport as soon as next year.

The last time two orbital-class U.S. rockets of similar type lifted off two days apart was in March 1995, when a Lockheed Martin Atlas 2AS rocket and a similar Atlas-E launcher flew separate missions from Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg Air Force Base, delivering an Intelsat broadcast satellite and an Air Force weather satellite to space.

Russian Soyuz rockets, on the other hand, have flown the same day from different launch pads, most recently in March 2015, when Soyuz boosters took off two hours apart from the Baikonur Cosmodome in Kazakhstan with a three-man space station crew and from the European-run space base in French Guiana with two Galileo navigation payloads.

A four-day delay in SpaceX’s previous launch from Florida, which carried a Bulgarian-owned communications satellite to orbit on a previously-flown, reused Falcon 9 booster, set up the weekend doubleheader.

Sunday’s mission began at 1:25:14 p.m. PDT (4:25:14 p.m. EDT; 2025:14 GMT), the instant when the Falcon 9 rocket could dispatch its 10 satellite passengers directly into one of the six orbital pathways populated by more than 60 Iridium communications spacecraft.

The 229-foot-tall (70-meter) Falcon launcher lifted off from Space Launch Complex 4-East at Vandenberg, the primary launch site on the U.S. West Coast. After climbing through a soupy fog bank enshrouding the hillside launch pad, the Falcon 9 steered through clear skies on a southerly trajectory with its nine Merlin 1D main engines producing 1.7 million pounds of thrust, chugging a super-chilled combination of RP-1 kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants.

After consuming most of its propellant, the first stage dropped away from the Falcon 9’s upper stage to begin a descent toward a SpaceX barge in the Pacific Ocean.

Four upgraded titanium grid fins, flying of the first time Sunday, extended from the top of the 14-story first stage and helped steer the rocket on its glide back to Earth. The booster ignited a subset of its Merlin engines twice, first to slow down for re-entry through the atmosphere, then to brake for landing.

A four-legged landing gear opened at the base of the booster just before touchdown, and the rocket braved high winds and challenging seas as it dropped through a low cloud deck onto the football field-sized drone ship, dubbed “Just Read the Instructions,” around eight minutes after blastoff.

The rocket will return to port in Southern California in a few days for inspections and possible reuse.

Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and chief executive, said the new, larger grid fin design is more robust than the Falcon 9’s previous aluminum fins, which had to be shielded against the extreme heat during re-entry, then replaced before the first stage could fly again.

The new fins are cast in a single piece of titanium and cut to form their shape, Musk tweeted. He said the titanium fins are “slightly heavier” than the shielded aluminum fins, but the upgrade offers more control authority for stabilization and steering as the pencil-like 14-story booster glides back to Earth.

The Falcon 9 rocket can land in heavier winds with the upgraded fins, Musk said.

“New titanium grid fins worked even better than expected,” Musk tweeted after Sunday’s landing. “Should be capable of an indefinite number of flights with no service.”

The billionaire entrepreneur also gave a brief update on SpaceX’s efforts to recover pieces of the Falcon 9 rocket’s payload fairings, the nose cone that protects satellites during the first few minutes of each launch. SpaceX intends to guide the fairing parts, which jettison from the rocket like a clamshell, with tiny thrusters and gently land them in the ocean with a parafoil.

“Getting closer to fairing recovery and reuse,” he tweeted. “Had some problems with the steerable parachute. Should have it sorted out by end of year.”

While the first stage made its daring descent, the second stage of the Falcon 9 rocket fired its single vacuum-rated Merlin engine into a preliminary parking orbit. After sailing over Antarctica, the upper stage reignited the Merlin engine for three seconds to reach a targeted 388-mile-high (625-kilometer) orbit to begin releasing the 10 Iridium satellites.

Fastened to a two-tier dispenser specially designed and built by SpaceX, the 1,896-pound (860-kilogram) satellites separated one-by-one at intervals of approximately 90 seconds. The deployments were complete by T+plus 1 hour, 12 minutes.

SpaceX and Iridium officials declared the launch a success, and ground controllers established radio contact with all 10 of the new satellites to verify they survived the trip into orbit.

“Ten for ten, it’s a clean sweep,” said Falcon 9 product manager John Insprucker, who provided commentary on SpaceX’s live webcast of the mission. “We can tie a broom to the Falcon 9.”

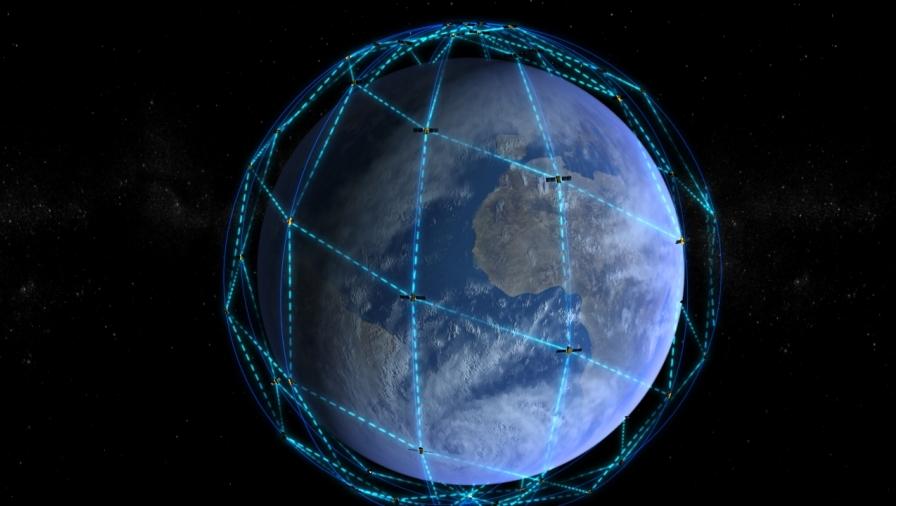

Sunday’s launch targeted Plane 3 of the Iridium constellation, which is designed to have 66 satellites spread out evenly in six orbital planes around Earth. One of of the satellites will fill a hole in Plane 3 where one of Iridium’s aging communications platforms failed last year.

It was the second of at least eight Falcon 9 flights to deliver 75 next-generation satellites to replace Iridium’s network with upgraded services and new spacecraft designed to operate for the next 15 years. Twenty of the satellites are now in space with the conclusion of Sunday’s mission.

Iridium ordered 81 of the new-generation “Iridium Next” satellites in 2010 from Thales Alenia Space, a French aerospace contractor. Thales partnered with Orbital ATK to build the spacecraft in an assembly line fashion in Orbital’s factory near Phoenix.

“Right now, it’s two down with six more launches to go,” said Matt Desch, chief executive officer of Iridium, in a post-launch press release. “Our operations team is eagerly awaiting this new batch of satellites and is ready to begin the testing and validation process. After several weeks of fine-tuning, the next set of ‘slot swaps’ will begin, bringing more Iridium Next satellites into operational service, and bringing us closer to an exciting new era for our network, company, and partners.”

“Specifically for this launch, five satellites … will go into mission in Plane 3, replacing existing satellites, or in one case, filling a hole in our network we’ve had for the last year or so,” Desch said in a pre-launch conference call with reporters. “Four satellites will be sent drifting down to Plane 2, where three of those satellites are expected to go into mission and one will be positioned as a spare.”

One more satellite launched Sunday will drift to Plane 4 and go into operation there next year. It takes 10 or 11 months to reposition an Iridium satellite to another orbital plane.

The satellites will boost themselves to a higher altitude — around 485 miles (780 kilometers) above Earth — in the coming weeks and months, rendezvousing with the older spacecraft each is intended to replace.

Desch said the satellites launched Sunday will replace aging members of the Iridium fleet that lifted off on a Russian Proton rocket from Kazakhstan in September 1997, and on two Boeing Delta 2 rockets from Vandenberg in March 1998 and February 2002.

The first-generation satellites were designed to last eight years, but most of them are still providing service, more than 20 years after the first batch of Iridium spacecraft reached orbit.

“Iridium Next features the same unique interconnected satellite architecture as the original constellation, which is the key feature that distinguishes Iridium from all other commercial satellite operators,” Desch said. “Cross-links, as we refer to them, allow our satellites to bounce data and voice calls around the world nearly instantaneously, creating a true web of coverage around the entire planet, the key advantage of our network and one of the biggest reasons for our growth and success.”

Improved service for Iridium’s nearly 900,000 subscribers will also come with the new satellites.

Besides faster connections on voice calls and data relays, the modern satellites are the cornerstone of Iridium Certus, which the company says will link customers on-the-go via an L-band network that is not as susceptible to interference from poor weather and other factors.

Desch said the Certus initiative will provide Iridium customers with up to 1.4 megabits per second of L-band connectivity, up from 128 kilobits per second available with the existing satellites.

“Certus is an L-band service built for reliability, coverage, mobility and able to be certified for safety services to ships and the cockpits of aircraft,” he said, adding that Certus will go to market in early 2018.

Iridium’s clients include the U.S. military, oil and gas companies, aviation and maritime operators, and mining and construction contractors.

Piggyback payloads on the Iridium satellites orbited Sunday will help commercial companies track and stay in contact with airplanes and ships outside the reach of land-based radars.

All of the Iridium Next satellites host radio receivers for Aireon, an affiliate of Iridium established in partnership with air traffic control authorities in Canada, Ireland, Italy and Denmark.

“Aireon technology is hosted by us on every Iridium Next satellite and is poised to change how the world views the skies,” Desch said. “The only way to really provide 100 percent global aircraft tracking and surveillance in realtime is through the Iridium network and our unique cross-link functionality that’s provided by our satellites.”

Don Thoma, Aireon’s CEO, told reporters his company’s service will help usher air traffic control into the modern era, making for more efficient use of airspace over oceans, where ground-based radars cannot see aircraft on intercontinental flights.

“When aircraft leave terrestrial airspace, they fly very rigid formations, typically conga lines or highways in the sky, along fixed routes to ensure that the aircraft maintain safe separation distances from one another, and make sure the air traffic system is as safe as it is,” Thoma said.

“That’s all in the process of being changed,” he said. “There’s a major upgrade by the world’s air traffic control organizations to move from a radar-based technology to a new GPS-based technology called Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast, or ADS-B.”

While ADS-B signals were originally meant to be received by ground stations and other aircraft, the Aireon payload on each Iridium Next satellite can detect them from space.

“ADS-B will provide realtime, very accurate, frequent updates on aircraft location to air traffic control,” Thoma said. “What Aireon represents is the ability to provide that not just over land-based areas, but over the entire world.”

Touting financial and environmental benefits in fuel costs and pollution reductions, Thoma said Aireon’s position data will help ensure airplanes are not lost over remote oceans, like the case of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370, a Boeing 777 that went missing with 239 passengers and crew in March 2014.

“We’ll be able to pick up those (position) signals and provide them in realtime to air traffic controllers,” Thoma said. “This will truly be a revolutionary aspect of air traffic control, not only supporting the surveillance across remote areas like the oceans, but also providing a backup capability and additional gap-filling surveillance over significant parts of land masses around the world.”

The first eight Aireon payloads aboard Iridium Next satellites launched in January are already receiving ADS-B position signals, he said.

Nine of the 10 Iridium Next satellites launched Saturday also have antennas to monitor maritime traffic for exactEarth, a Canadian company, and Harris Corp. of Melbourne, Florida, according to Nicole Schill, an exactEarth spokesperson.

Like all eight of Iridium’s launches booked with SpaceX, Sunday’s flight used a brand new Falcon 9 first stage.

SpaceX has racked up two successful launches with recycled Falcon 9 boosters, including Friday’s mission from Florida, which coincidentally was powered by the first stage that sent the first 10 Iridium Next craft to space in January from California.

“I believe previously-flown boosters are fantastic,” Desch said. “I think it’s revolutionizing the industry. I think it’s fantastic, in the future, for the availability and cost of launches.”

Desch said he was inclined, for now, to continue launching Iridium satellites on newly-built Falcon 9s.

“Our using them or not using them is not a statement around the quality or capability of those boosters,” he said.

Instead, Desch would like to see a steeper discount for flying on a reused Falcon 9 booster than SpaceX currently offers. Perhaps most importantly, he said, is determining whether a switch to a previously-flown Falcon 9 rocket will get Iridium’s satellites up sooner.

Iridium’s first 10 satellites were supposed to launch last September, but the flight was grounded until January in the wake of a Falcon 9 rocket explosion in Florida. A manufacturing bottleneck at SpaceX’s headquarters near Los Angeles delayed the second Iridium Next flight from April to June.

“When would they be available, and would they improve the current launch plan we have with brand new rockets that I basically contracted for a number of years ago, and have budgeted for and have paid for?” Desch said. “That’s the first thing. Will they improve my schedule because schedule, to me, is very, very important.”

“Secondly is the cost, and really the cost and risk are kind of aligned,” he said. “I believe the risk is pretty low right now, but it’s not zero because it’s a new thing.”

He said the reduced cost of a reused Falcon 9 is “minor right now, at least in our perception of it.”

“If that changes as there are additional launches, I’ll reconsider that, but right now I think we’ve made the right decision.”

“While we are currently flying first-flown launches, I’m open to previously-flown launches, particularly for maybe the second half of our launch schedule — maybe in 2018 — but I really want to see the answers to all those questions before we’d ever make that kind of decision,” Desch said.

The next Falcon 9 flight is set for takeoff from Kennedy Space Center’s launch pad 39A some time next month. It will send an Intelsat high-throughput communications satellite toward its perch in geostationary orbit more than 22,000 miles (35,000 kilometers) over the equator.

Vandenberg is set to host its next Falcon 9 launch in late August, when it will loft a long-delayed Taiwanese Earth observation satellite, according to Taiwanese news reports.

Then 10 more Iridium satellites are set to go up on another Falcon 9 from Vandenberg some time in early fall.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.