A series of achievements in China’s space program over the last 12 months have set the stage to start construction of the country’s first space station in 2019, a year later than previously scheduled, officials said Friday.

“Since 2016, we have successfully launched the Long March 7 carrier rocket, the Tiangong 2 space lab, the Shenzhou 11 manned spacecraft and the Tianzhou 1 cargo spacecraft,” said Wang Zhaoyao, director of the China Manned Space Agency. “The four flights achieved success in China’s manned space program, and laid a solid foundation for the building and long-term operation of a space station.”

The Long March 7 rocket is vital for launching supply ships, and eventually crews, to China’s future space station. It has now flown two times successfully.

The Tiangong 2 orbital module launched in September 2016, welcoming two Chinese astronauts on the Shenzhou 11 spacecraft in October for a one-month expedition, the country’s longest human spaceflight to date.

The heavy-lifting Long March 5 rocket — not mentioned by Wang — took off on its maiden flight in November. The powerful launcher is needed to place heavy space station modules into orbit.

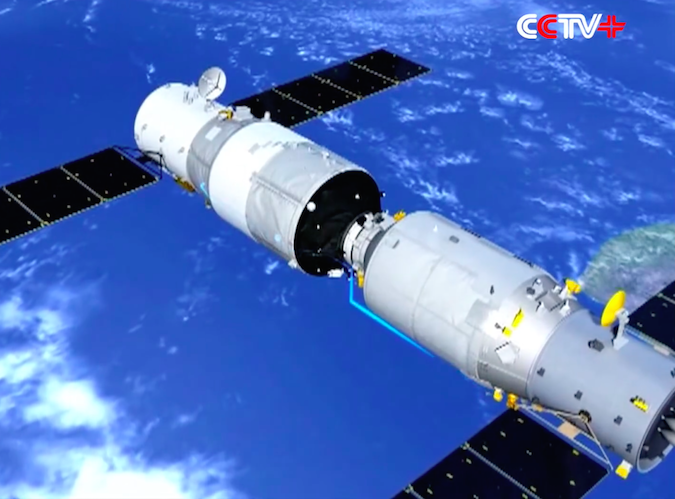

And the Tianzhou 1 robotic cargo craft launched on a Long March 7 rocket April 20, linked up with Tiangong 2 two days later, and accomplished China’s first in-space refueling test on Thursday.

The rapid-fire launch campaign has bolstered confidence that the key components needed for China’s space program will be ready when construction begins, officials said.

A core module, named Tianhe 1, is scheduled for launch in 2019 to begin assembly of the space station. Two support sections will launch by 2022 to complete construction of the space station, which officials said should be operational for at least 20 years.

Three-person crews will live on the space station for three-to-six months, officials said. The finished outpost will have a mass of more than 60 metric tons, about one-seventh that of the International Space Station, and comparable to the mass of NASA’s Skylab station in the 1970s.

With crew and cargo transport ships docked, the station’s mass will rise to around 90 metric tons, or 200,000 pounds.

“From June of last year to yesterday, four planned flight missions of the space lab phase were all completed,” Wang said in a press conference Friday. “In retrospect, we have taken note of many important achievements and successful experiences that are worth learning.”

China’s latest mission, Tianzhou 1, demonstrated the country’s ability to resupply and refuel the future space station. Weighing more than 28,460 pounds (12,910 kilograms) at liftoff, the robotic cargo craft was the largest and heaviest spacecraft ever launched by China.

Tianzhou 1 will remain docked with the Tiangong 2 space lab until around late June, then spend three months conducting standalone experiments before re-entering Earth’s atmosphere.

“In the next phase, the cargo spacecraft will remain docked with the space lab as they orbit together,” Wang said. “The cargo spacecraft will also undock and fly alone and try different approaches to improve in-orbit refueling technology. After that, the cargo spacecraft will land under control in a designated area in the South Pacific Ocean, while the space lab will remain in space for further exploration.”

The solar-powered Tianzhou 1 spacecraft will detach from Tiangong 2 and attempt a “fast rendezvous” profile on another approach to the space lab in the coming weeks, according to Wang. The rendezvous trajectory will mimic the path future cargo missions will take, allowing for delivery of supplies and fuel the same day of launch.

“The current rendezvous and docking process needs two days for preparation,” Wang said. “If the technology of autonomous fast rendezvous and docking technology succeeds, we only need six-and-a-half hours for rendezvous and docking between two spacecraft. It will greatly enhance our work efficiency.”

Russian Progress supply ships and Soyuz crew ferry craft often dock with the International Space Station around six hours after liftoff.

Chinese officials say the Tianzhou resupply missions will carry up to 14,300 pounds — 6.5 metric tons — of cargo to the planned orbital complex. The fuel transfer system will deliver up to 4,600 pounds — 2.1 metric tons — of liquid propellant to the station’s propulsion system.

“The payload ratio and the amount of propellant refueling are on a par with current international standards for space cargo transportation systems, if not being ahead of them,” Wang said.

The Tianzhou cargo carrier is bigger than the International Space Station’s current visiting vehicles, capable of ferrying more equipment than Russia’s Progress, the U.S.-built commercial Cygnus and Dragon, and the Japanese HTV spaceships.

“As the last (test) mission before the space station is built, the mission is significant in serving as a link between past and future,” Wang said.

Tianzhou means “heavenly vessel” in Chinese.

The simulated cargo aboard Tianzhou 1 represents the equipment a three-person crew would need for one month in space, officials said. The payloads include crew provisions, water tanks and oxygen and nitrogen vessels designed to replenish the space lab’s breathable atmosphere.

While no crews will be present during Tianzhou 1’s mission, the freighter carries several experiments, including one on “non-Newtonian” gravity, according to Chinese media reports.

Zhao Guangheng, chief designer of the space lab’s utilization system, said the non-Newtonian gravitational experiment will verify the performance of a high-precision electrostatic suspension accelerometer.

“The accelerometer performance index has reached the international advanced level, which will provide important technical support for our country to carry out research of basic space physics, weak force measurement and gravity gradient measurements,” Zhao said Friday.

Other research investigations will study the proliferation and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into germ cells to gather data on the possibility of human reproduction in space, China’s state-run Xinhua news agency reported.

The stem cells and embryos of mice are also on-board Tianzhou for an experiment into how animals and humans could regrow lost tissues and organs, Xinhua said. Researchers also sent up an experiment to test out a new medicine for osteoporosis.

Wang told reporters Friday that Tianzhou 1 will also deploy an experimental CubeSat later in its mission and test other technologies.

“An advanced navigation, guidance and control device and new domestic-made components will be tested in orbit,” Wang said. “An active vibration isolation technology will also be tested. Those tests will be carried out one-by-one.”

Future Tianzhou spacecraft could carry replacements for large station components, like a solar array wing, service other satellites in orbit, and be repurposed as a deep space tug for missions to the moon, according to Yang Baohua, vice president of the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corp., the Chinese spacecraft’s lead contractor.

Asked whether Tianzhou supply ships could fly to the International Space Station, Yang replied that China’s exclusion from the program — a policy enshrined in U.S. law — means the spacecraft is not technically compatible with the ISS docking mechanisms.

“Because of this, the technological standards, such as the interfaces, are yet to be unified, and that is why the docking cannot be fulfilled in the short term,” Yang said. “However, the aerospace staff in China is willing to work on behalf of the International Space Station, because space exploration, the manned endeavor, should be a cause shared by the entire human race in peace.”

Wang Zhaoyao from China’s human spaceflight agency said the country’s engineers plan to make their spacecraft fit with a variety of possible destinations.

“China is enabled by both of its technologies and competence to transport freight to the International Space Station,” Wang said. However … we need, specifically, to take a step further to solve problems with different interfaces, which has drawn considerable concern from the international community. In the past few years, the country has been engaged in standardizing the interfaces of its spacecraft, especially in regard to manned spaceflights. It’s like the diversity of cell phones which cannot be recharged because of unmatched outlets.”

Since China’s first astronaut flight in 2003, crews have performed automated and manual docking maneuvers and conducted a spacewalk.

Wang said the modules for China’s space station are undergoing preliminary testing, and officials have signed cooperation agreements with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs to provide experiment opportunities for scientists from all nations, including developing countries.

Zhao, who is responsible for experiments on the space station, said the orbiting research complex will host science and engineering investigations across a range of disciplines.

He identified life science, biotechnology, microgravity fluid dynamics, combustion science, materials science, basic physics, astronomy and astrophysics, space environment monitoring, Earth observation and technological demonstrations as key areas for experiments on the Chinese space station.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.