Astronauts will not fly to the International Space Station on SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spaceship until at least May 2018, NASA said this week, missing a previous target launch date at the end of next year.

The delay was expected after Boeing, which is also developing a commercial crew capsule, announced earlier this year its spaceship would not be ready for crew ferry missions until at least mid-2018, and after a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket exploded during a ground test on a Cape Canaveral launch pad in September.

In an emailed statement, SpaceX said its Crew Dragon development program has stayed on track this year despite the suspension of Falcon 9 launches in the wake of the explosion, but the company said it needs more time to process the outcome of the mishap investigation.

“We are finalizing the investigation of our Sept. 1 anomaly and are working to complete the final steps necessary to safely and reliably return to flight,” SpaceX said. “As this investigation has been conducted, our commercial crew team has continued to work closely with NASA and is completing all planned milestones for this period.

“We are carefully assessing our designs, systems, and processes taking into account the lessons learned and corrective actions identified,” SpaceX said. “Our schedule reflects the additional time needed for this assessment and implementation.”

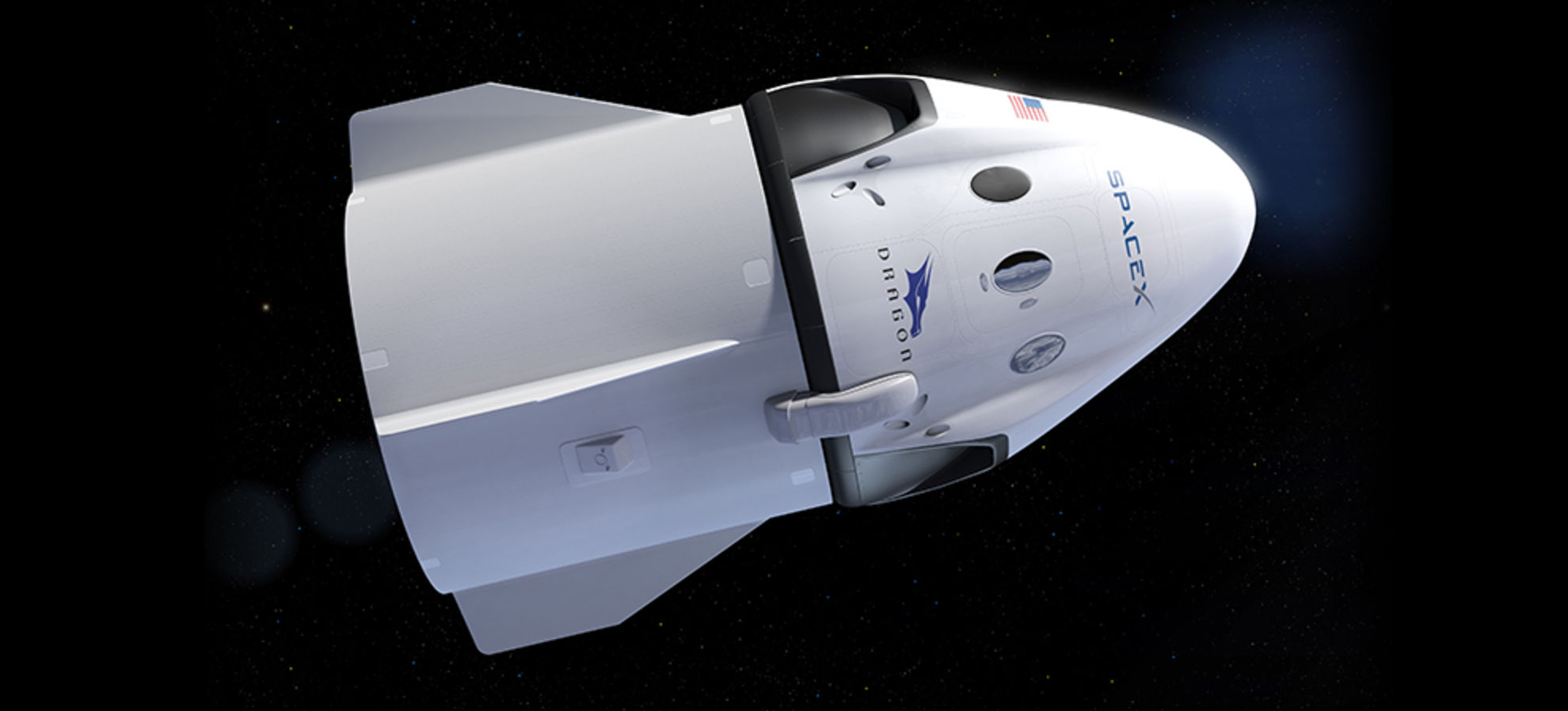

An unpiloted test of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule in Earth orbit is now set for November 2017, followed by a demo mission to the space station with two astronauts in May 2018, according to NASA’s schedule update.

SpaceX already flies cargo-carrying Dragon spacecraft to the space station, but the Crew Dragon is a new development.

“To meet NASA’s requirements, the commercial providers must demonstrate that their systems are ready to begin regular flights to the space station,” the agency said in a statement. “Two of those demonstrations are uncrewed flight tests, known as Orbital Flight Test for Boeing, and Demonstration Mission 1 for SpaceX. After the uncrewed flight tests, both companies will execute a flight test with crew prior to being certified by NASA for crew rotation mission.”

SpaceX has a $2.6 billion contract from NASA’s commercial crew program to complete development of the Crew Dragon spacecraft and fly at least two crew rotation missions to the space station. Boeing has a $4.2 billion contract to finish testing of its CST-100 Starliner capsule and also execute a minimum of two crew rotation sorties.

Both companies have contract options for up to six operational crew ferry flights to and from the space station. NASA has already decided to approve SpaceX and Boeing for two “post-certification” missions each.

Boeing’s schedule calls for an automated orbital test flight of the CST-100 Starliner in June 2018, followed by a demonstration with two crew members in August 2018.

Boeing attributed its delay to problems in production and qualification testing of spacecraft components, and and the redesign of the CST-100’s aerodynamic shape to fix an aero-acoustic launch issue uncovered in wind tunnel testing.

The Crew Dragon missions will blast off on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket from launch pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, the former launch site for the space shuttle and Apollo moon missions. Nearby Complex 41 is being outfitted for CST-100 Starliner launches on United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 boosters.

The latest delays for NASA’s commercial crew program partners leave little room for further slips without forcing NASA officials to seek another contract extension with Russia’s space agency — Roscosmos — to keep U.S. astronauts flying to the space station aboard Soyuz spaceships past 2018.

NASA’s latest Soyuz seat purchase covers opportunities to launch U.S., European, Japanese and Canadian astronauts through the end of 2018, with landing reservations secured through mid-2019.

One top NASA manager, human spaceflight chief Bill Gerstenmaier, has said it may be too late to buy more Soyuz seats from Russia. Kirk Shireman, NASA’s space station program manager at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, said the space agency faced a deadline by the end of the year to extend its crew transportation contract with Roscosmos.

Officials have said Russia needs at least two years of notice to manufacture enough Soyuz capsules to meet NASA’s needs.

The U.S. space agency is paying Russia $82 million per astronaut seat on Soyuz launches in 2018, and a year’s worth of seats in 2019 would likely cost more than $500 million.

Once SpaceX and Boeing begin service to the orbiting research complex, NASA and Russia plan to begin an “in-kind” agreement in which a U.S. astronaut will fly on each Soyuz mission and a Russian cosmonaut will launch on each Crew Dragon or CST-100 spacecraft with no funds exchanged.

The arrangement is necessary to keep at least one Russian and one U.S. crew member on the space station to operate each section of the outpost if Russian, SpaceX, or Boeing capsules are grounded due to technical problems.

One point of contention between SpaceX and NASA safety advisors has been the company’s plan to strap in Crew Dragon passengers on the launch pad before fueling of the Falcon 9 rocket with super-chilled densified liquid oxygen and kerosene propellants.

Under SpaceX’s proposed timeline, ground teams would close the hatch to the Crew Dragon once the astronauts were inside, then evacuate the pad for filling of the Falcon 9 propellant tanks, a concept known as “load and go.”

The Sept. 1 explosion on SpaceX’s Florida launch pad occurred during the final phase of fueling, and SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk said last month the mishap most likely occurred when the liquid oxygen — chilled to near its freezing temperature — froze on the outside of a high-pressure helium tank inside the Falcon 9’s second stage.

Thomas Stafford, a retired U.S. Air Force general and former astronaut, chairs NASA’s International Space Station Advisory Committee. He has aired his concerns about SpaceX’s fueling plan in public meetings and in a letter to Gerstenmaier, the space agency’s top human spaceflight manager.

“There is a unanimous, and strong, feeling by the committee that scheduling the crew to be on board the Dragon spacecraft prior to loading oxidizer into the rocket is contrary to booster safety criteria that has been in place for over 50 years, both in this country and internationally,” Stafford wrote in a letter to Gerstenmaier before SpaceX’s Sept. 1 explosion. “Historically, neither the crew nor any other personnel have ever been allowed in or near the booster during fueling. Only after the booster is fully fueled and stabilized are the few essential people allowed near it.”

SpaceX said the Crew Dragon’s pusher escape system would be armed and ready to propel the capsule away from the rocket in the event of a major problem during fueling.

“Over the last year and a half, NASA and SpaceX have performed a detailed safety analysis of all potential hazards with this process,” SpaceX said.

NASA’s Safety Technical Review Board approved a “hazard report” documenting SpaceX’s safety controls in July, two months before the launch pad mishap.

“As with all hazard analyses across the entire system and operations, controls against those hazards have been identified, and will be verified prior to certification,” SpaceX said. “These analyses and controls will be carefully evaluated in light of all data and corrective actions resulting from the anomaly investigation. As needed, any additional controls will be put in place to ensure crew safety, from the moment the astronauts reach the pad, through fueling, launch, and spaceflight, and until they are brought safely home.”

A SpaceX spokesperson said representatives from the company recently met with Stafford and the ISS Advisory Committee to answer their questions on the matter.

Production of the first space-rated Crew Dragon spaceship, destined to fly on the unpiloted demo mission in late 2017, is “well underway,” SpaceX said.

The California-based company completed its final major Crew Dragon design review earlier this year.

Other Crew Dragon milestones accomplished in 2016 include the completion of qualification testing of the capsule’s docking system and spacesuits, testing of the ship’s environmental control and life support system, multiple parachute tests, and key steps in the development of the craft’s propulsion system, according to SpaceX.

The initial Crew Dragon missions will splash down in the ocean suspended under four main parachutes. SpaceX aims to certify the capsule for helicopter-like propulsive landings in the future.

“Next year’s primary focus will be wrapping up final testing of the propulsion and parachute systems, completing the build of the Demo 1 vehicle, and completing the Demo 1 mission,” SpaceX said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.