Targeting a resumption of Antares cargo launches to the International Space Station as soon as July, Orbital ATK plans to roll out an upgraded Antares rocket to a launch pad in Virginia this week for a 30-second firing of the booster’s new engines.

Technicians working at the Antares launch site on Virginia’s Eastern Shore are finishing up preparations for a series of tests and dress rehearsals for the rocket’s return-to-flight.

The first Antares launch in nearly two years is set for early July, perhaps as soon as July 6, with a Cygnus supply ship carrying logistics, provisions and experiments to the space station and its six-person crew.

Before the cargo mission, dubbed OA-5 in Orbital ATK’s flight sequence, is cleared for blastoff, engineers have several more major tests in store for the upgraded Antares rocket.

The next step is scheduled as soon as this week with the rollout of an Antares first stage booster to pad 0A at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia, according to Blake Larson, Orbital ATK’s chief operating officer.

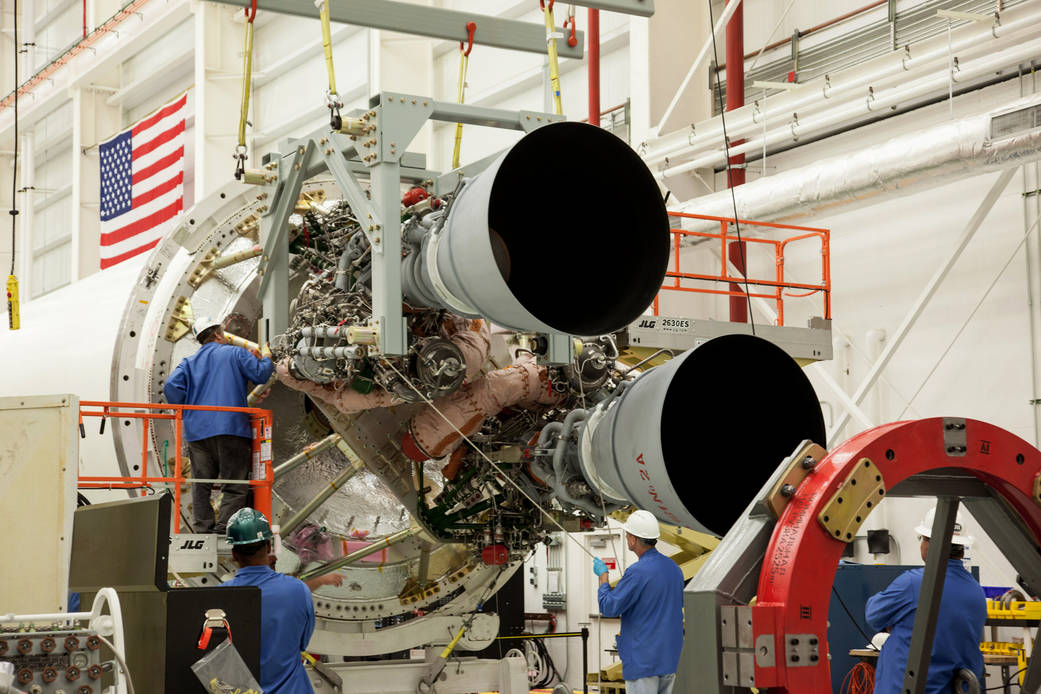

Fitted with two newly-built RD-181 engines from Russia, the Antares first stage will roll out of its Horizontal Integration Facility at Wallops for the one-mile trip south to the launch pad, where it be hoisted vertical for several weeks of tests.

One of the first tests will be a wet dress rehearsal, in which the Antares launch team will load kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants into the booster.

“We’ll basically run the pre-launch sequence and go right up to the point of firing the engines. We’ll load all the commodities. We’ll load all the pressurant gases. We’ll apply all the purges. We’ll get everything ready and see everything work properly between the vehicle and the pad systems, and then we’ll stop the test right before engine ignition,” said Kurt Eberly, Orbital ATK’s Antares deputy program manager.

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Kurt Eberly. Become a member today and support our coverage.

“We’ll detank and look at all that data. If that all looks good, roughly a week or so later, we’ll re-initialize the sequence, load the tanks, and go for the hotfire test.

The 30-second test firing of the twin-engine first stage is scheduled for late May.

The engines will be programmed to ramp up to full power — equivalent to more than 800,000 pounds of combined thrust — and go through a steering check as the control computers throttle the engines to different thrust levels they will see in flight.

“We want to see steady-state operation at each of the operating points in flight,” Eberly said. “Once we hit those points, we have some mixture ratio excursions that we will command, and then we’ll also be vectoring the nozzles during the test with varying frequency content looking to excite any adverse modes and interactions between the components.”

Orbital ATK ordered RD-181 engines from Russia’s NPO Energomash, the builder of the Atlas 5 rocket’s RD-180 engine, in the wake of a catastrophic launch failure moments after a liftoff from Virginia in October 2014. The Antares rocket crashed near the Antares launch pad, toppling two of the facility’s lightning protection towers and carving a huge crater just northeast of pad 0A’s elevated launch mount.

A commercial Cygnus cargo freighter en route to the International Space Station with supplies was destroyed in the failure.

Investigators from Orbital ATK and NASA concluded the fiery mishap started about 15 seconds after liftoff inside a liquid oxygen turbopump on one of the rocket’s first stage AJ26 engines.

The engines were built more than 40 years ago by the Soviet Union’s Kuznetsov Design Bureau for the N1 moon rocket. When the Soviet moon program was canceled, officials put the engines — called NK-33s in Russia — in long-term storage before Aerojet Rocketdyne imported the powerplants to the United States in the 1990s.

Aerojet Rocketdyne modified the engines for use on U.S. launchers, qualifying the NK-33s for U.S. propellants and adding mechanisms for in-flight steering. The company renamed the upgraded engines as AJ26s.

Orbital ATK intended to move away from the AJ26 engine before the 2014 launch failure, but the accident accelerated the company’s plans. Officials announced two months after the rocket crash that NPO Energomash would provide newly-built RD-181 engines for future Antares launches.

Since the first two RD-181 engines arrived from Russia last year, ground crews at Wallops have mated the powerplants to the Antares rocket’s Ukrainian-made first stage structure. The booster and RD-181 engines set for the hotfire test later this month are assigned to fly on the OA-7 launch scheduled at the end of 2016.

The RD-181 engine generates 13 percent more thrust than the AJ26 and burns its mix of kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants more efficiently, Eberly said in an interview with Spaceflight Now.

“The combination of those two (improvements) give us a good 20 to 25 percent performance improvement to the orbit that we’re flying to in low Earth orbit to inject the Cygnus for these cargo runs,” Eberly said.

The single-chamber RD-181 is similar to the dual-nozzle RD-180 engine flown on United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5, producing about the thrust of its larger cousin. NPO Energomash produces a nearly identical engine named the RD-191 for Russia’s Angara rocket family.

The new version of the rocket is known as the Antares 230 configuration, according to Orbital ATK.

Eberly said the new engines required a new type of thrust adapter, a structural component that mechanically connects the RD-181s to the first stage. Orbital ATK also built avionics systems for the engines, developing the new controllers in-house to replace the AJ26 controller sourced from an external supplier, Eberly said.

“It’s about the same physical size as the AJ26,” Eberly said. “It uses the same propellants. The combustion cycle (is the same), which means that the mixture ratio between the two propellants — between the kerosene and the liquid oxygen — is very close.”

Each engine is individually steered to guide the Antares rocket in flight, and designers positioned the RD-181 engine nozzles in the same place as the AJ26 engine cones, minimizing changes to the launch pad and ground support equipment.

“The new components were the engines, obviously, the new thrust adapter, and then feedlines, which are the pipes that connect the core tanks to the engines, and then some new avionics and software to control it all,” Eberly said. “That was really what changed. Everything forward of the first stage is identical.”

Orbital ATK builds the solid-fueled Castor 30XL second stage for the Antares rocket. It is unchanged from the upper stage on previous Antares models.

The higher-performing RD-181 engines will alter the Antares rocket’s launch profile, Eberly said. Because the new engines will consume fuel from the same first stage tanks first designed for the AJ26, they will drain the propellant supply faster.

“Whereas with the AJ26, we were on the order of 235 seconds of first stage burn, we’ll be down around 214 seconds for these RD-181s,” Eberly said. “They will just consume the propellants that much faster.”

The Italian-built cargo module for the next Cygnus mission arrived at the Wallops launch site earlier this year. The service module, containing power and propulsion for the supply ship, will be transported from Orbital ATK’s headquarters and factory in Dulles, Virginia, to Wallops in mid-May, officials said.

The company’s commercial Cygnus cargo freighter continued flying while Orbital ATK readied the Antares for flights with the new engines. Orbital ATK ordered two Atlas 5 rocket launches in December 2015 and in March to continue executing on its more than $2 billion contract with NASA to deliver cargo to the space station.

The commercial cargo contract, initially signed in 2008 for eight missions, now has provisions for at least 11 resupply flights. NASA extended the agreement twice — for two additional flights last year, then again earlier this year for one more cargo launch.

SpaceX is NASA’s other commercial provider for cargo transportation services. Its agreement originally covered 12 missions but has been extended like Orbital ATK’s. SpaceX now has 20 logistics flights under contract with its Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon capsule.

SpaceX and Orbital ATK have flown 13 of the 31 cargo missions — eight and five launches respectively — with each company suffering one launch failure. The cargo providers are not required to re-fly missions that fail.

NASA announced in January winners of follow-on commercial cargo contracts to cover the space station’s logistics needs from 2019 through 2024. SpaceX, Orbital ATK and Sierra Nevada Corp., a newcomer to the cargo delivery service, won that competition, with each firm guaranteed at least six missions in the six-year period.

With the latest contract extension, Orbital ATK has 12 or more missions on the manifest for the Antares rocket through the early 2020s. Some future Cygnus cargo missions may blast off on ULA’s Atlas 5 rocket, but most will fly on the Antares, officials said.

“Beyond this year, with the new extension mission added (and) with the the new CRS-2 contract coming online, the base level of demand really throughout the middle of the next decade for Antares should run at two or three launches per year,” said David Thompson, Orbital ATK’s president and CEO. “That gives us a solid foundation on which we can increase market reach of the vehicle and flight rates as well.”

Once the Antares rocket resumes flights, Orbital ATK hopes to lure more customers to fly satellites on the booster, which can place medium-sized spacecraft into low-altitude orbits favored by Earth observation platforms.

Thompson said Orbital ATK designed to Antares to offer the company solid profit margins at modest launch rates. Engineers working on the Antares program also contribute to other projects within Orbital ATK’s portfolio, and the launcher uses the same systems flying on other company products, he said.

“As we go from two or three launches per year to up to six launches per year, there’s a lot of operating leverage in that,” Thompson said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.