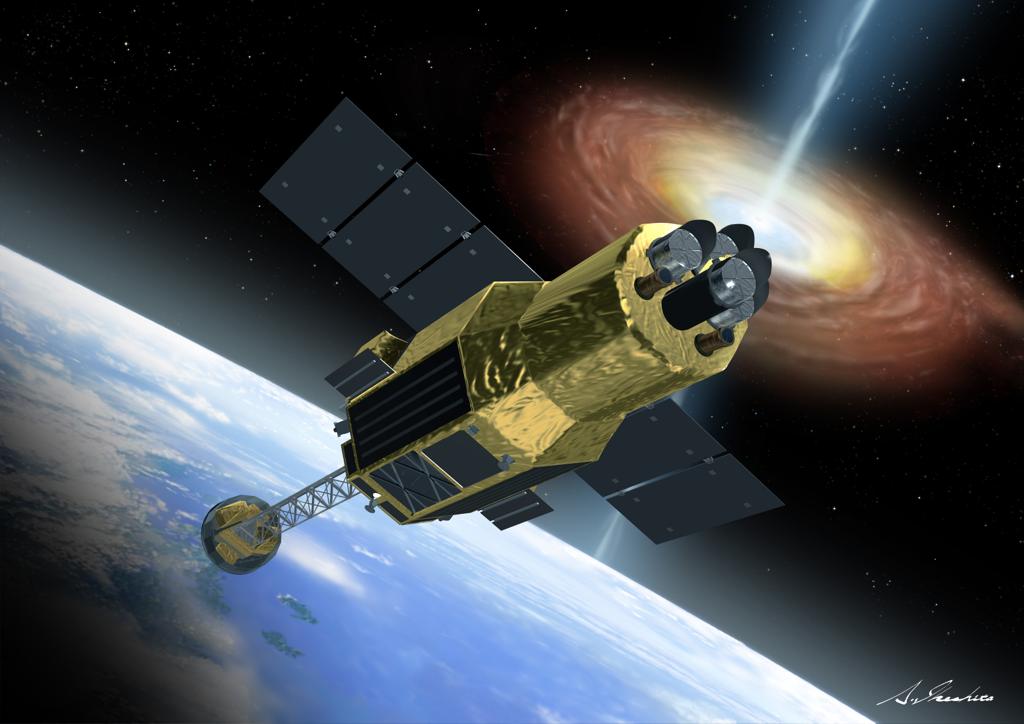

Japan’s Hitomi X-ray observatory was beset by a series of attitude control problems March 26 that caused the satellite to spin out of control and shed sizable chunks of its power-generating solar panels or deployable telescope, according to engineers analyzing fragments of telemetry data sent to Earth by the dying spacecraft.

Hitomi, also known as Astro-H, first showed signs of trouble March 26, and mission control last heard from the satellite March 28, less than six weeks after its Feb. 17 blastoff on a planned three-year mission.

The problem started when the satellite’s inertial reference unit detected Hitomi was rotating around its Z-axis at 21.7 degrees per hour. The spacecraft was actually stable at the time, mission managers from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency said Friday.

The satellite’s attitude control system commanded Hitomi’s reaction wheels, rapidly-spinning devices which control the pointing of the spacecraft with momentum, to counteract the spin. The action caused the satellite to rotate in the opposite direction as the faulty inertial reference unit indicated, officials said.

Momentum accumulated inside the reaction wheel system, and magnetic torquers aboard the satellite were unable to unload the building momentum, which neared the reaction wheels’ design limit.

Hitomi’s computers recognized the dangerous situation and put the satellite into safe hold a few hours later. The satellite tried to stabilize using the craft’s hydrazine-fueled rocket thrusters to aim its solar panels toward the sun.

But the trouble was not over, and the spacecraft’s solar sensor was unable to find the sun. Struggling to correct the growing spin rate, small rocket firings inadvertently caused Hitomi to rotate faster due to a bad setting in the thruster system, JAXA officials said.

Ground controllers updated Hitomi’s thruster control parameters Feb. 28 to adjust for the spacecraft’s new mass properties after deployment of the observatory’s extendable optical bench, a 6-meter (20-foot) structure that holds imagers to detect high-energy X-rays emitted by super-heated matter being sucked into black holes.

The new control parameters uplinked to Hitomi Feb. 28 were inadequate and did not properly account for the deployed telescope structure, JAXA said.

Hitomi was still in a functional testing phase when the anomaly occurred. Normal science observations were supposed to begin later this year.

The observatory was supposed to study X-rays emitted by hot plasma that hold clues about the inner workings of the mysterious black holes, the lives of galaxies, the structure of galactic clusters and where clumps of dark matter may reside in the universe.

Formed by the powerful supernova explosions of old stars, black holes give off X-rays as they ingest matter, sending beams through the universe that can only be detected by telescopes with sensors like those aboard Hitomi.

While engineers hope the Hitomi satellite could slow its rotation rate in the coming days and weeks, one senior official said scientists might have to give up on the mission.

“We haven’t given up hope for recovery, but we may have to think about the worst-case scenario,” said Saku Tsuneta, vice president of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, in a press conference last week, according to a report by Kyodo News.

Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said the chances of resuming Hitomi’s science mission are low.

“The chance of recovery is not zero, but seems pretty slim,” said McDowell, who is not directly affiliated with the Hitomi mission but closely tracks global space activity.

Japanese space officials said April 8 that the spacecraft shed multiple pieces early March 26, Japanese time, with the largest about a meter, or 3 feet, in size. The U.S. military’s Joint Space Operations Center, or JSpOC, said it detected 10 pieces come off the main body of the Hitomi spacecraft.

JAXA says the largest of the 11 objects attributed to the Hitomi satellite measures up to 10 meters (33 feet) in diameter, and engineers are sure that piece is the spacecraft’s primary structure.

The Japanese-run Subaru Telescope in Hawaii imaged Hitomi to study its condition, officials said.

The spacecraft’s largest remaining fragment is spinning once every 5.2 seconds, too fast to sustain a charge on the satellite’s battery with its solar panels.

“One of (the) possible causes to result in such high rate spin is (an) anomaly of the attitude control system,” said Azusa Yabe, a spokesperson for JAXA’s Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, which manages the Hitomi mission. “If the satellite spins rapidly, solar paddles, the extended optical bench (EOB), and so on, could break out from the satellite because they are structurally weak.”

Yabe told Spaceflight Now that ground controllers are still attempting to contact the satellite.

Smaller objects shed by Hitomi could re-enter Earth’s atmosphere as soon as May, according to estimates by satellite observers.

The main body of the satellite will likely remain in orbit until at least the mid-2020s, when solar activity picks up and generates more atmospheric drag in Earth’s upper atmosphere, hastening the craft’s uncontrolled re-entry, McDowell said.

Astronomers billed Hitomi as the most important X-ray mission of the decade.

Hitomi’s X-ray sensors were designed to see cosmic phenomena invisible to the human eye, seeing through veils of gas and dust that obscure observations with conventional telescopes.

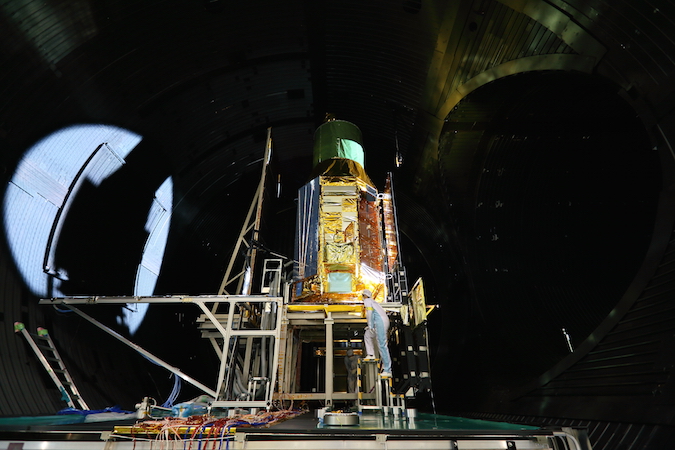

Japan spent 31 billion yen, or about $280 million, on the Astro-H project, including financing most of the mission’s instruments, satellite bus and H-2A launch vehicle.

NASA helped develop an advanced “microcalorimeter” aboard Hitomi designed to register X-ray photons and measure their energy with high sensitivity, collecting data that will tell astronomers about the composition and velocity of the super-heated matter that produced the light.

The U.S. space agency contributed $54.9 million to hardware development for the Soft X-ray Spectrometer on the Hitomi mission, according to Felicia Chou, a NASA spokesperson. NASA planned to spend a total of $130 million on the project, a figure which included on-orbit support, science activities, and the hardware development costs, she said.

No such instrument has ever returned data from space before, and scientists were eager for its results, which were to reveal information about the environment around black holes.

First developed in the 1980s, the microcalorimeter technology was supposed to fly aboard a NASA observatory that eventually became Chandra, which launched in 1999, but cost concerns kept the sensor off the mission.

Earlier versions of the Soft X-ray Spectrometer launched on two Japanese X-ray missions in 2000 and 2005, but the first was destroyed in a launch failure, and the second ran into trouble weeks after liftoff and ran out of liquid helium coolant before observations began, rendering the instrument useless.

Scientists hoped for a better outcome this time.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.