Updated at 3 p.m. EDT on June 29.

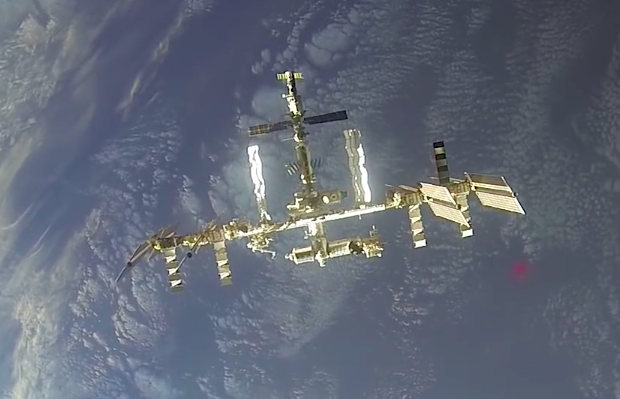

Managers in charge of International Space Station say the massive orbiting laboratory and its residents can keep going despite Sunday’s failure of a SpaceX resupply launch, which destroyed a new docking adapter critical to NASA’s commercial crew program, a spacesuit, and a part to repair the lab’s water purification system.

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket disintegrated minutes after liftoff from Cape Canaveral, marking the commercial launcher’s first failure in 19 missions and destroying more than 4,000 pounds of gear needed on the space station.

It was the third failure of a space station supply mission in eight months, extending a string of problems that contrasts with a nearly perfect launch record of flights to the complex from 1998 until 2014. All but one mission to assemble and resupply the space station reached the outpost in that time, a nearly 16-year period covering more than 150 launches.

“It’s a pretty important loss to us,” said Bill Gerstenmaier, head of NASA’s human spaceflight division. “I don’t want to minimize the loss to us, but, again, from a macro-level standpoint, the crew is in no danger.”

Sunday’s loss will still have consequences for the space station, likely delaying or changing NASA’s plan to ready the complex to receive U.S. crew spaceships, cutting into research aboard the outpost and adding to the importance of Russian and Japanese resupply missions due for launch in the next two months.

First up will be the launch of Russia’s Progress M-28M cargo craft Friday — the first flight of the venerable supply vessel since a Progress capsule spun out of control after a botched separation from its Soyuz rocket in April.

Investigators traced the failure to a peculiarity in the stiffness of the connection between the Soyuz third stage and the Progress spacecraft, a problem that Russia’s space agency said is limited to Progress launches on the modernized version of the Soyuz booster flown in April.

The Progress mission set for launch on an older Soyuz rocket configuration at 0455 GMT (12:55 a.m. EDT) Friday from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, and NASA officials said they expect no delay in response to Sunday’s Falcon 9 mishap. Russia’s space agency on Monday confirmed on Twitter that the launch remained scheduled for Friday.

Russian managers moved up the Progress launch from August to July 3 to quickly replace the supplies lost on the Progress freighter earlier this year.

The Aug. 16 launch date for a Japanese HTV supply ship could be shifted to give NASA time to add time-critical cargo to the mission, Suffredini said. No such decision has been made, but Suffredini told reporters Sunday to expect adjustments in upcoming logistics missions.

“This is a big loss — I don’t want to underplay that — but I do want everyone to know that, as a program, we’re managing this in a way to keep us healthy, and we’ll pick ourselves up and get on to the next flight, and continue to do research on-board ISS,” Suffredini said.

Since the retirement of Europe’s Automated Transfer Vehicle, space station managers have four ways to ship up supplies to the complex, and three of the cargo carriers are grounded, or are just coming back from failures.

The crash of an Orbital ATK Antares cargo rocket in October started the run of mishaps. Like SpaceX, the Virginia-based company has a contract with NASA to ferry supplies to the outpost aboard commercially-operated supply vehicles.

Orbital ATK’s Cygnus cargo freighter is supposed to launch before the end of the year on a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket. Company officials contracted with ULA for the Atlas 5 launch as engineers redesign the Antares rocket for a new engine to replace the powerplants blamed for last year’s crash.

The launch is set for December — currently the earliest opportunity in the Atlas 5’s busy manifest this year — but Orbital ATK says the Cygnus spacecraft could be ready for flight in October if a slot opens in ULA’s schedule.

Despite the supply shortfall, Suffredini said the space station has enough food and water to keep the crew going until late October, even if no more cargo arrives.

The station is currently staffed by a three-person crew, and another trio of residents is due for launch on a Soyuz ferry craft July 22. NASA and Russian authorities are sticking with that plan, pending a final review by U.S. engineers to ensure the crew capsule is not susceptible to the same problem that doomed the similar Progress spaceship in April, according to Suffredini.

“We have (consumables) well into October, probably late October if nothing else flew,” Suffredini said. “We have plenty of opportunities for resources to come to ISS to keep the crew going. Therefore, we should continue because without the crew, we can’t get our logistics vehicles there. With a limited crew, we have a very difficult time doing some of the repairs we have to do to keep the systems going so we can do the research.

“We are not in a position today to stand down on crew flights,” Suffredini said. “In fact, we’re quite healthy on orbit, but we’re always in a safe position — if the time comes — that if we decide we don’t have the logistics to support the crew, we always have a vehicle there that can bring them home safely, and we would certainly do that. But we’re not even close to that kind of conversation today given the logistics we have on-board.”

NASA has little cargo aboard the Progress flight preparing for launch Friday, and Suffredini said there were no immediate plans to rush any equipment to the Kazakh launch base to replace items destroyed on SpaceX’s Falcon 9.

But officials are likely to reshuffle the cargo manifest for the Japanese HTV mission in August.

One data point requiring close attention by space station ground controllers is the lab’s water filtration system. Filters in the water purification system are close to being saturated.

New filtration beds were aboard the Dragon capsule lost Sunday. Another set of filters went down with Orbital ATK’s Antares rocket last year.

“The multi-filtration beds we have in the water processor today are starting to get full, as indicated by the measurements we’ve been taking lately,” Suffredini said. “When it starts to get full, we take water samples and bring them home to understand specifically what the constituents are. The constituents in the water are not a risk to the crew at the levels that we see today.”

If the contaminants in the water reach unsafe levels, engineers could elect to switch off the filtration system and direct the crew to consume fresh water shipped up from Earth or water already pre-filtered and stored in the space station’s tanks.

The space station’s environmental system recycles bathwater, urine, sweat and humidity in the lab’s atmosphere, passes it through a series of purification devices, and adds it back to the potable water supply for drinking by the astronauts.

“We are reaching the limit where we’d say we would stop using the water processor,” Suffredini said. “I expect that we have some flexibility in that number.”

Water bags are slated to fly to the station on the Progress launch Friday and next month’s Japanese supply delivery.

“Unfortunately for us, this was the second set of multi-filtration beds that we lost, and we just don’t have that fast of a pipeline, so the team is off building the next set of multi-filtration beds,” Suffredini said. “I doubt very seriously we’ll have them ready in time for the August flight of the HTV.”

A docking adapter outfitted to receive the next generation of human-rated spaceships, plus a radio to communicate with the approaching spacecraft, was another victim of Sunday’s rocket failure.

The Boeing-manufactured docking mechanism was one of two adapters built to attach to the space station’s space shuttle-era docking ports. The adapters use a new, lighter design to receive commercial crew spacecraft expected to begin flying to the complex in 2017.

In the wake of the shuttle’s retirement, NASA turned to the private sector to route cargo and crews to the space station and end the agency’s reliance on Russia for transport services to low Earth orbit.

The resupply mission cut short Sunday was SpaceX’s seventh full-up cargo flight to the space station. Orbital ATK conducted two missions to delivery equipment to the station before its failure last year. SpaceX and Orbital ATK have multibillion-dollar contracts for 15 and eight resupply missions, respectively.

Language in NASA’s contract with SpaceX does not require the California-based rocket company to refly Sunday’s doomed mission. However, the contractor will not receive a final post-flight payment owed by the government after a successful mission, according to Suffredini.

NASA does purchase insurance for its missions.

The space agency planned for the commercial cargo transport services to lead to new U.S. crew vehicles. The space agency in September 2014 selected Boeing and SpaceX to develop the CST-100 capsule and a highly-modified version of the Dragon spacecraft to host astronauts on the trip between Earth and the space station.

The CST-100 and Crew Dragon vehicles are designed to mate with the two new docking receptors.

The docking system, a centerpiece of a more than $100 million project to rejig the space station for new astronaut transport spacecraft, was packed inside the Dragon supply craft’s unpressurized trunk section. An identical adapter was supposed to fly to the research complex in December, giving the space station two ports equipped to receive U.S. crew capsules.

It is not clear when the next docking system could fly to the station while SpaceX looks into the cause of Sunday’s failure.

“The good news is we have a second docking adapter, and ultimately the radio system has two radios, so we only flew one each on this flight,” Suffredini said. “Those are available, so we will be able to continue to press towards (having) the docking system on-board ISS to support the commercial crew program when they come online.”

Parts exist on the ground to assemble a third docking adapter if required, according to Suffredini.

A spacesuit stowed inside the Dragon’s internal cabin, eight small CubeSats designed to image the Earth for San Francisco-based startup Planet Labs, an IMAX camera, computers, and an array of experiments also went down with Sunday’s failure.

The experiments were needed to support more than 35 research investigations on the space station over the next few months. The gear was designed to look at meteors streaking through Earth’s atmosphere, track how the human body responds to prolonged exposure to microgravity, study combustion and fire propagation in space, and demonstrate holographic technology in orbit, among other fields.

Suffredini said the Dragon’s unique capacity to return major hardware and research specimens to Earth would not be missed by the grounding of the SpaceX cargo ship while engineers probe Sunday’s mishap.

SpaceX’s last cargo flight, which returned to Earth in May, nearly emptied the space station’s storage freezers, he said.

Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and chief operating officer, declined to predict how long it would take to find the cause of the Falcon 9’s high-altitude anomaly, which occurred about 2 minutes, 19 seconds, after liftoff from Cape Canaveral.

“I don’t have a timeline for that right now,” she said. “It certainly isn’t going to be a year. I imagine a number of months or so, but, again, I don’t want to speculate.”

The early focus of the investigation, which is led by Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of mission assurance and chief engineer, is on an over-pressurization event noted in telemetry data from the Falcon 9’s second stage.

NASA released a full listing of the cargo aboard the failed mission:

- Crew Supplies — 690 kilograms (1,521 pounds)

- 92 Food BOBs, 2 Bonus Food Kits, 2 Fresh Food Kits

- Crew Provisions, Crew Care, ODF

- Utilization — 573 kilograms (1,263 pounds)

- Canadian Space Agency: Vascular Echo Exercise Band

- European Space Agency: Circadian Rhythms, KUBIK EBOXes, Interface Plate, EPO Peake, BioLab, Spheroids, EMCS RBLSS, Airway Mon., LiOH Cartridge

- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency: Atomization, Biological Rhythms, Multi-omics, Cell Mechanosensing 3, Plant Gravity Sensing 3, SAIBO L&M, Space Pup, Stem Cells, MSPR LM, Group Combustion Camera

- US: 2 Polars, 6 DCBs and Ice Bricks, 1 MERLIN, FCF/HRF Resupply, HRP Resupply [Kits, MCT, Microbiome, Twin Studies], IMAX Camera, Meteor, Micro-9, MSG Resupply, NanoRacks Modules & 0.5 NRCSD #7, Universal Battery Charger, Veg-03, Microbial Observatory-1, Microchannel Diffusion Experiment, Wetlab RNA Smartcycler, SCK, Story Time, MELFI TDR Batteries

- Computer Resources — 36 kilograms (79 pounds)

- Projector Screen, Sidekick, OCT Laptop & Power Supply, 32GB MicroSD Cards, Generic USB Cables, Power Modules and Card Readers, Preloaded T61p Hard Drives, CD Stowage Container, Network Attached Storage Devices, XF305 Camcorders, RS-422 Adapter Cables

- Vehicle Hardware — 462 kilograms (1,018 pounds)

- CHECS CMS: HRM Watches, Bench Lock Studs, Glenn Harness for Kelly, Kopra and Peake

- CHECS EHS: CO2 Monitoring Assemblies, Filter Assemblies, CSA-CP/CDM Battery Assemblies, SIECE Cartridge Assemblies, Water Kit, Petri Dish Packets

- CHECS HMS: IMAKs, Oral Med Packs

- C&T: C2V2 Communications Unit (and HTV-5 Unit Data Converter)

- ECLSS: 3 Pretreat Tanks, Filter Inserts, 9 KTOs, UPA FCPA, CDRS ASV, IMV Valve, Wring Collector, Water Sampling Kits, OGS ACTEX Filter, ARFTA Brine Filter Assemblies, O2/N2 Pressure Sensor, NORS O2 Tank, 3 PBA Assemblies, 2 MF Beds, 2 Urine Receptacles, Toilet Paper Packages, H2 Sensor, Ammonia Cartridge Bag, PTU XFER Hose

- EPS: 2 Avionics Restart Cables

- Makita Drill, PWD Filter, N3 Bulkhead Connectors, Yellow/Red Adapters, IWIS Plates, 6.0 & 4.0 Waste Xfer Bags, BEAM Ground Straps, JEM Stowage Wire Kit

- EVA Hardware — 167 kilograms (368 pounds)

- SEMU, REBA, EMU Ion Filters (4), Equipment Tethers, Gas Grap, EMU Mirrors, Crew Lock Bags, SEMU arms/legs

- Lindgren/Yui ECOKs & CCAs, Lindgren LCVG

- Kelly LCVG, Padalka EMU Gloves

- Russian Cargo

- Russian Segment Torque Wrench

- Unpressurized Cargo — 526 kilograms (1,159 pounds)

- IDA #1

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.