NASA’s Orion spacecraft achieved all but two of 87 demo objectives on its first orbital flight last month, but details on the capsule’s performance will require dismantling the spaceship’s outer skin in a careful procedure designed to keep most of the Orion prototype intact for future testing.

Orion’s engineering and production teams are back at work this week at Kennedy Space Center after the spaceport’s annual holiday shutdown. Engineers from Lockheed Martin, Orion’s prime contractor, will collect data recorded during the craft’s Dec. 5 test flight and submit a final post-mission report to NASA by March 5, according to Jules Schneider, Lockheed Martin’s Orion operations manager at KSC.

Their first tasks will be draining the capsule of hazardous hydrazine propellant and ammonia coolant left over from the four-and-a-half hour test flight.

After launching from Cape Canaveral aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta 4-Heavy rocket, the spacecraft reached a peak altitude of 3,600 miles and flew twice around the world before splashing down in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Baja California.

The test flight was designed to prove the performance of Orion’s heat shield, computers, separation events and other systems.

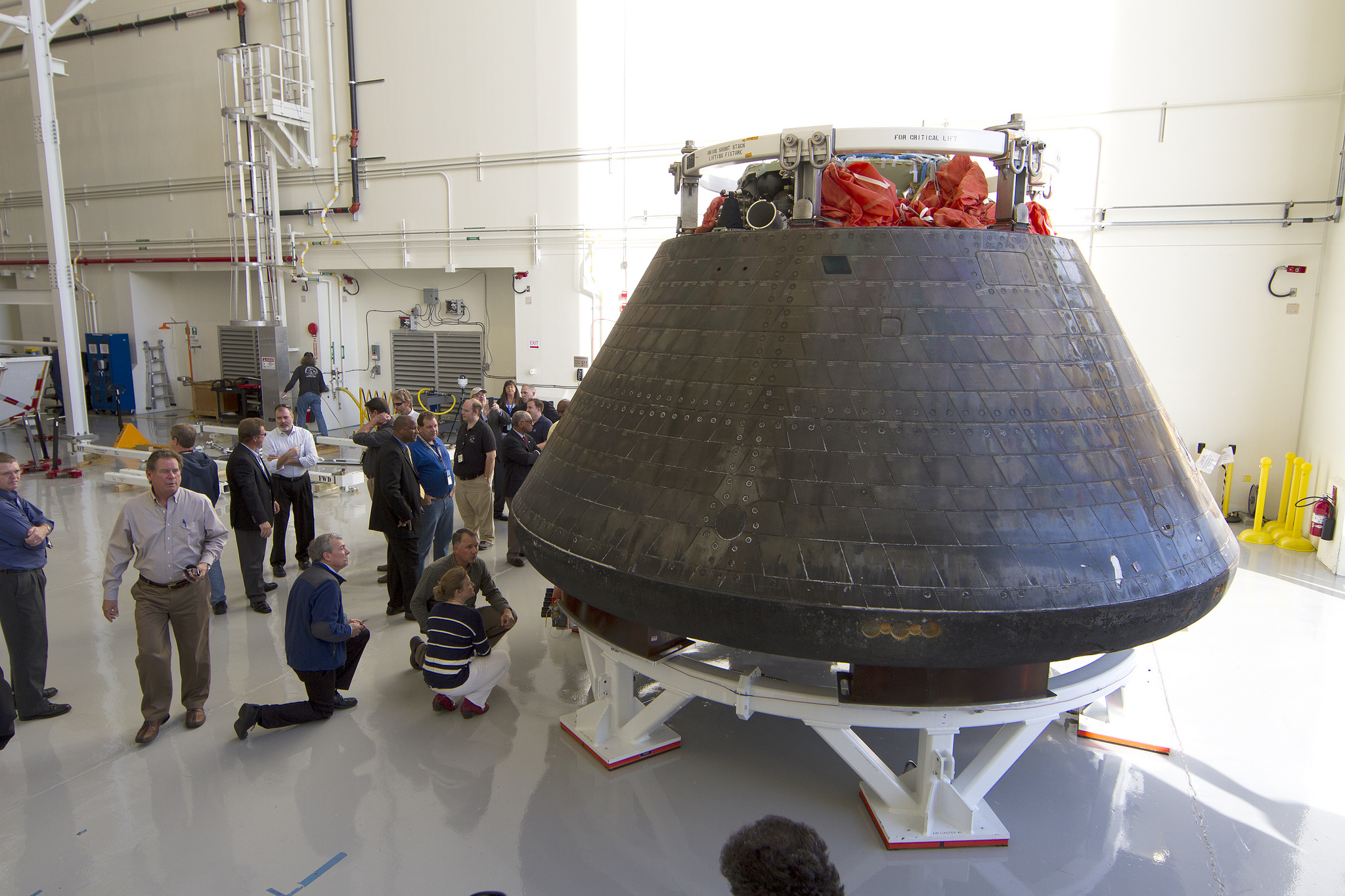

A team of U.S. Navy divers stationed on the USS Anchorage amphibious transport ship recovered the capsule from the Pacific for return to port at San Diego. Technicians packed the spacecraft in a shipping container for an eight-day road trip back to Kennedy Space Center, where it arrived Dec. 18.

Officials plan to move the Orion spacecraft between several KSC facilities in the next few months. It spent the holiday break inside the Launch Abort System Facility at KSC and will next move to the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility, where workers in hazmat suits will decontaminate the capsule after emptying its reservoirs of hydrazine and ammonia, Schneider said.

In the coming weeks, Lockheed Martin’s Orion team will remove panels covered in black ceramic tiles from the capsule’s backshell, exposing the spaceship’s olive-green aluminum- lithium metal structure, underlying wiring and plumbing, and avionics boxes for inspection.

The spacecraft’s blackened ablative 16.5-foot diameter heat shield is also slated for removal and analysis, Schneider said.

Engineers are wary of taking apart the innards of the capsule beyond the disassembly of the craft’s cocooning outer shell, Schneider told reporters in a briefing Dec. 19.

“There is a lot of debate right now as to how much of the vehicle we’re going to take apart,” Schneider said. “Because the vehicle performed so well, there are some people re-thinking how much we want to disassemble — and how much do they want to keep assembled — so we can use it going forward on the ground doing testing, etc.”

The Orion spacecraft that flew Dec. 5 is not expected to fly on another space mission, but NASA and Lockheed Martin plan to use the vehicle for an ascent abort test in 2018. The capsule will launch on a modified rocket motor from a Peacekeeper missile before initiating an abort sequence to validate Orion’s ability to escape from a failed launch.

The only technical failures on the Dec. 5 test flight were with the spacecraft’s inflatable airbags, which would flip the capsule upright if it splashed down upside down.

Four of the spaceship’s five airbags pressurized, but two of the bags quickly lost air, leaving two of the orange spheres inflated.

“Those were the only objectives on the entire flight that were not met,” Schneider said.

“Everybody is incredibly pleased with the performance of the vehicle,” Schneider said. “I think you can tell it came through the trial by fire pretty well.”

Schneider said the metallic skeleton of the next space-rated Orion spacecraft is due to arrive at KSC from a welding facility in New Orleans in November 2015. It will be outfitted with computers, a European-built propulsion and power module and other gear ahead of its launch scheduled for 2018.

Like Orion’s Dec. 5 flight test, the 2018 mission will not carry astronauts but will blast off aboard NASA’s new heavy-lifting Space Launch System mega-rocket on a flight around the moon. A crewed Orion mission will follow around 2021.

While observers often focus on when the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System will be ready for the next flight, managers in charge of preparing ground systems at KSC say they are also racing the clock.

“The long road ahead is kind of a two-edged sword,” said Phil Weber, senior technical integration manager for KSC’s Ground Systems Development and Operations program, which oversees KSC’s upgrades to support SLS and Orion missions.

“We got the baseline configuration of what SLS and Orion are going to look like in 2011, so about three years ago,” Weber said. “We’ve got about three more years to go until EM-1 (Exploration Mission-1 in 2018) … We’re at hump day right now.”

Major work to be completed before the 2018 launch includes modifications to the mobile launch platform originally built for the canceled Ares 1 rocket. NASA and contractor teams are also upgrading cranes inside the huge Vehicle Assembly Building and installing new platforms inside the high bay where the SLS and Orion will be stacked for launch.

“We have a tremendous amount to complete in the next three years, so although we want to do the launch as soon as we possibly can, we’ve got to get all of the ground systems put in, validated, ready to receive the flight hardware and then do the processing for the launch,” Weber said. “You can look at it both ways. We want to launch soon, but we’ve got to have the time to get it ready.

“It’s scary to me that we’ve got three years to do all this work,” Weber said.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.