STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS “SPACE PLACE” & USED WITH PERMISSION

NASA is gearing up for a milestone unmanned test flight Thursday, the first launch of the agency’s Orion deep space exploration spacecraft intended to one day carry astronauts on missions beyond low-Earth orbit to the vicinity of the moon, one or more nearby asteroids and, eventually, Mars.

Liftoff atop a United Launch Alliance Delta 4 heavy-lift booster from launch complex 37 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station is targeted for 7:05 a.m. EST (GMT-5) Thursday, the opening of a two-hour 39-minute window. Forecasters are predicting a 60 percent chance of favorable weather.

The $370 million mission “is absolutely the biggest thing that this agency’s going to do this year,” said William Hill, deputy associate administrator for Exploration Systems Development. “This is really our first step in our journey to Mars.”

While that might seem a stretch considering no one expects astronauts to visit the red planet before the 2030s, Mike Hawes, Lockheed Martin’s Orion program manager, said the new spacecraft represents a major milestone in NASA’s post-shuttle evolution and its plans to fly astronauts beyond low-Earth orbit for the first time since the Apollo moon landings.

“There’s always a danger of over hype, but we have now built a spacecraft that is human rated for the first time in 42 years,” he said in an interview with CBS News. “And so from that standpoint, I think it’s really significant.

“Granted, it’s a stepping stone in the early cadence, it takes longer than most of us would want, but (it gets) people to think about the fact that you have to design a different spacecraft to go out beyond the space station than what we have been doing in low-Earth orbit for so long. So that’s where I think it is, maybe, worthy of the hype.”

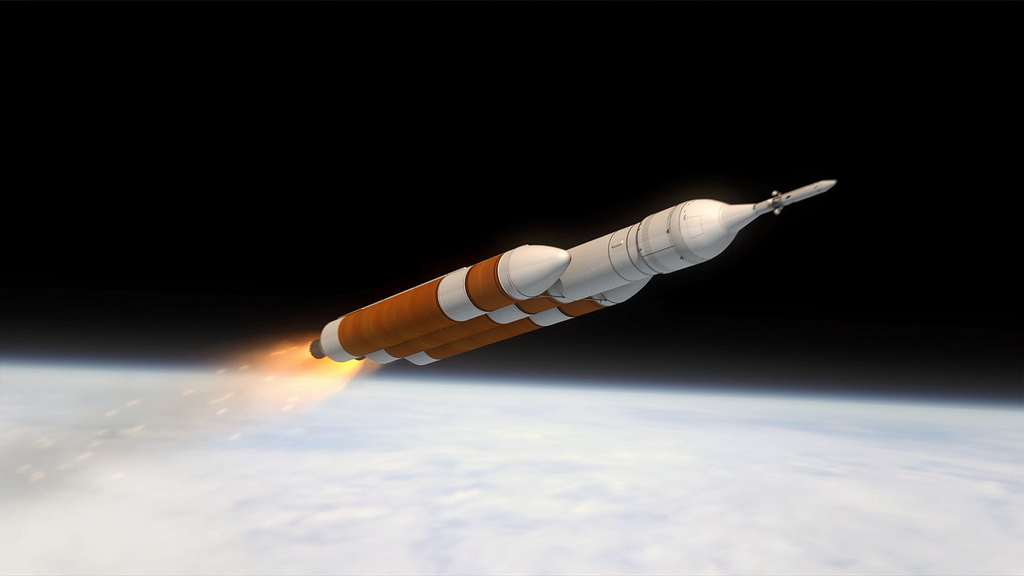

If all goes well, the Delta 4, generating a ground-shaking 2 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, will boost the 19,000-pound Orion capsule into an initial orbit with a low point of 115 miles and a point around 550 miles. Then the second stage will fire again to raise the apogee of the second orbit to around 3,600 miles three hours after launch. That’s nearly 14 times higher than the International Space Station’s orbit.

After separating from the Delta 4’s second stage, the heavily instrumented Orion capsule will plunge back to Earth, slamming into the discernible atmosphere at a velocity of nearly 20,000 mph and enduring peak re-entry temperatures of some 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit before a parachute descent to splashdown 600 miles west of Baja California.

The re-entry velocity and heating, the most extreme that can be achieved with a Delta 4, will be about 84 percent of what an Orion capsule would experience coming home from the moon.

The primary goals of Exploration Flight Test 1 — EFT-1 — are to test Orion’s 16.5-foot-wide heat shield, its computer hardware, software and navigation systems and to verify the high-tech electronics can endure the higher radiation levels found outside the protection of the Van Allen belts that shield space station astronauts.

“That’s a big issue for the computers,” said Mark Geyer, NASA’s Orion program manager. “With these processors that now are so small, they’re great for speed and size but they’re more susceptible to radiation.”

The flight also will give engineers a chance to test a variety of critical pyrotechnic systems needed to jettison structural panels, the capsule’s launch fairing and dummy abort motor, to separate the spacecraft from the booster and to deploy the huge parachutes needed for a safe descent.

And while the Orion used for EFT-1 is not equipped with seats, cockpit displays or a European Space Agency-supplied service module housing propulsion, life support and solar power systems, “you could fly people in this primary structure, you could fly people with this heat shield and with these parachutes,” Geyer said.

“This is real hardware that we intend to fly people on, and we are flying it now in space and we will update as needed for things we learn,” he said.

The EFT-1 mission is being carried out under a commercial contract with Lockheed Martin, which bought Delta 4 launch services from ULA and has overall responsibility for the flight. NASA managers will participate in the launch decision and flight controllers at the Johnson Space Center in Houston will monitor Orion’s systems from launch through landing.

“It is truly a commercial endeavor,” Hill said. “The launch and entry are both FAA licensed with ULA having license for the launch and Lockheed Martin for the entry. Our mission operations folks and our ground systems folks are basically subcontractors to Lockheed Martin, both doing the mission ops and the flight ops as well as the actual recovery.”

Lockheed Martin designed and built the Orion spacecraft and still owns the hardware. But follow-on vehicles eventually will be turned over to NASA after government contract requirements are met.

“EFT-1 is basically a compilation of the riskiest events we’re going to see when we fly people,” said Geyer. “So this test flight is a great opportunity for us to fly those and to actually see them in operation. Some of these events are very difficult or even impossible to test on the ground. So it’s important to fly them. EFT-1 gives us a chance to put all those together in a test flight.”

Bryan Austin, a former NASA flight director who serves as Lockheed Martin’s EFT-1 mission manager, said the test flight will help make production capsules “as safe as we possibly can.”

“Critical to that is the thermal protection system and demonstrating its performance in a high-energy entry return similar to what we would see coming back from deep space and beyond the moon,” he said. “We’re building a very safe and reliable spacecraft and looking forward to taking it beyond Earth orbit, beyond the moon, exploring deep space and then soon, taking us to Mars.”

The Orion spacecraft is the only major element of the Bush administration’s Constellation moon program that is still in development. As originally envisioned, Orion would have carried four astronauts at a time to low-Earth orbit where the spacecraft would link up with a lander for the flight to the moon. Orion then would carry the returning astronauts back to Earth.

The Obama administration, citing high costs, cancelled Constellation and opted instead for a two-tiered “flexible path” approach to manned spaceflight. Boeing and SpaceX ultimately won contracts to build commercial crew capsules to ferry astronauts to and from the space station.

NASA retained Lockheed Martin’s Orion capsule to serve as the centerpiece of a new government-operated deep space exploration program, relying on a new mega rocket, the Space Launch System booster, to propel astronauts beyond low-Earth orbit. NASA spent $5.8 billion on the Orion project when it was part of the Constellation program and another $3.3 billion since 2012, pushing the price tag to $9.1 billion to date.

Following the EFT-1 mission, NASA plans to launch another uncrewed Orion capsule atop the SLS rocket for the booster’s maiden flight — Exploration Mission 1, or EM-1 — in 2018. That flight will feature an operational ESA-supplied service module.

The first piloted Orion mission, EM-2, is targeted for launch in 2021. A variety of potential mission scenarios are under study, including a looping flight around the moon.

While Orion/SLS development proceeds, NASA plans to build a robotic spacecraft to capture a small asteroid, or a piece of one, and tow it back to the vicinity of the moon. Agency managers plan to meet Dec. 16 to decide on a specific mission architecture, setting the stage for initial spacecraft design work next year.

After EM-2, NASA hopes to launch two astronauts aboard an Orion capsule to rendezvous with the captured rock, collect samples and return them to Earth for detailed laboratory analysis. The long-range goal is to launch at least one Orion/SLS flight per year to carry out a variety of missions leading to an eventual flight to Mars.

But it will not be easy. NASA’s budget must pay for International Space Station operations through 2024, fund development of the new Boeing and SpaceX commercial crew ferry craft, pay for development of the huge SLS rocket, continue development of Orion and fund the agency’s myriad unmanned science probes, Earth observation missions and aeronautics.

The asteroid redirect mission, or ARM, has failed to garner widespread support in the science community and faces challenges in Congress from lawmakers who believe it makes more sense to test hardware and procedures on the moon before venturing into deeper space.

But NASA managers say the asteroid redirect project is crucial to the agency’s long-range plans.

First, they say, expanded observations leading to an asteroid retrieval mission will help scientists identify threatening asteroids and comets and provide valuable hands-on experience needed for development of techniques to divert a body on a collision course with Earth.

Second, the flights will serve as valuable shakedown cruises to perfect the systems and procedures needed for the much longer voyages to Mars and its two moons using Orion and a yet-to-be-designed habitation module.

“We’ll do a series of missions, one of which is the asteroid retrieval mission, that will sequentially start buying down risk of what we need to do to go to Mars,” Hill said.

“We are taking a look at after EM-2, trying to do a mission every year. We’ll see if the budget supports that, we believe it does right now. Obviously, we’re going to have to figure out a way to reduce costs for operations and we’re addressing those now. And then we’ll have to build kind of a funding wedge to develop other things like a habitation module.”

NASA is counting on international participation to help offset U.S. costs. The European Space Agency already is supplying the service module directly below Orion that will house the capsule’s main propulsion system, life support equipment, solar arrays, radiators and other critical components.

Regardless of how the politics plays out and where NASA might ultimately be directed to go, Hawes said Orion will be up to the task. Since development began in 2006, the capsule “has been considered as a space station resupply vehicle, it’s been considered in a lunar architecture, it’s been considered in Lagrange point architectures, deep retrograde orbits,” he said.

“When you look at that, you see the design has been pretty robust in that it hasn’t taken big, major changes to go from one of those to another. … I think we’ve got a sound vehicle we can (use to) really get started on this mission.”