A novel NOAA climate observatory with a unique past arrived at Cape Canaveral on Thursday to begin two months of launch preparations, testing, and fueling before liftoff aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

The Deep Space Climate Observatory — known as DSCOVR — was transported by truck from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland to an Astrotech satellite processing facility in Titusville, Fla., just outside the gates of Kennedy Space Center.

The spacecraft arrived Thursday, and engineers planned to unpack the satellite inside a clean room to prepare DSCOVR for launch.

Workers will hand over the 1,256-pound (570-kilogram) satellite to SpaceX in January for attachment to the company’s Falcon 9 launcher at Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad. Liftoff is targeted for Jan. 23.

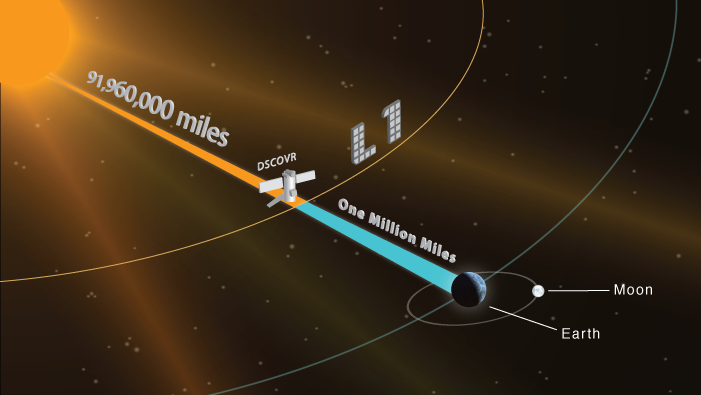

DSCOVR is a joint project between NOAA, NASA and the U.S. Air Force. The satellite will be positioned at the L1 libration point a million miles away from Earth, where its instruments will monitor space weather and the solar wind for a planned five-year mission.

A swarm of charged particles approaching Earth from the sun can interfere with transportation and electrical infrastructure. A report by the National Research Council in 2009 concluded a large solar storm impacting Earth could cost between $1 trillion and $2 trillion, and it could take up to a decade to recover from the event.

“We must always stay on top of developing solar storm activity and provide accurate, timely forecasts,” said Mike Simpson, the DSCOVR program manager at NOAA. “DSCOVR will extend our capability to do that.”

The spacecraft will serve as a sentinel to warn scientists on Earth of approaching solar storms, giving up to an hour of lead time to inform commercial airlines, electric utility operators, and communications and GPS users of a potential disruption.

NASA’s aging Advanced Composition Explorer — launched in 1997 and operating well beyond its design life — is currently the only spacecraft capable of supplying such warning to NOAA’s space weather forecast team.

“The instruments on DSCOVR will improve upon what we have with ACE, as they will continue to operate even during severe space weather storms. The DSCOVR data will also be used to drive the next generation of space weather models, allowing forecasters to specify where on Earth the storm conditions will be at their worst,” said Doug Biesecker, DSCOVR program scientist at NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center in Boulder, Colo.

The DSCOVR spacecraft was originally developed for launch in the late 1990s for the Triana mission, a NASA-led project to study Earth’s climate and how much solar energy was being absorbed and reflected by Earth. Named for the sailor who first spotted land on Columbus’s 1492 voyage to the Americas, the Triana mission had its genesis in an initiative backed by former Vice President Al Gore, who in 1998 proposed launching a satellite on the space shuttle to record live around-the-clock imagery of Earth from deep space.

NASA suspended work on the Triana mission in 2001, then canceled the project in 2005, citing the dwindling number of remaining shuttle flights and a lack of funding to refurbish and launch the satellite.

NOAA saw a use for the Triana spacecraft, which NASA kept under climate-controlled storage at Goddard for seven years, when scientists noticed a potential gap in solar storm warnings as the ACE satellite outlived its planned lifetime.

Engineers took the spacecraft out of storage and put it through testing and modifications for launch on unmanned rocket.

DSCOVR still hosts the Earth science instruments originally planned for the Triana mission, including a camera to capture true color images of the full disk of Earth every two hours and a sensor to measure how much solar energy affects the planet’s climate.

NOAA is in charge of the mission and operating DSCOVR after liftoff, and NASA is overseeing preparations on the spacecraft. The U.S. Air Force agreed to pay for a Falcon 9 rocket to launch the satellite.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.