It turns out Pluto’s distinct haze layer carries a bluish hue, and deposits of water ice poking out from the frozen world’s crust are covered in a red sheen, scientists said Thursday.

Armed with fresh insights each week, researchers probing Pluto’s mysteries are now applying data from the New Horizons spacecraft’s full instrument to answer key questions about the dwarf planet’s structure and geologic processes.

The haze ring around Pluto was first resolved in black and white by New Horizons’ telescopic high-resolution camera just after the probe passed by the icy world July 14. The latest view comes from the spacecraft’s Ralph color camera.

“That striking blue tint tells us about the size and composition of the haze particles,” said Carly Howett, New Horizons science team researcher from the Southwest Research Institute. “A blue sky often results from scattering of sunlight by very small particles. On Earth, those particles are very tiny nitrogen molecules. On Pluto they appear to be larger — but still relatively small — soot-like particles we call tholins.”

Close-up imagery of the haze revealed complex layering scientists are struggling to explain, but a leading theory is that nitrogen and methane particles sublimated and lofted from Pluto’s icy surface react with ultraviolet sunlight high in Pluto’s rarefied atmosphere, creating small, lightweight particles called tholins, which have the characteristics of soot.

The tholins settle back on Pluto’s surface, and the material gives off the reddish color widespread on Pluto’s crust. Some geologists also believe some tholins that escape from Pluto’s weak gravitational grasp are captured on the moon Charon, which has a large red feature near its frigid north pole.

The cycle gives rise to a tenuous weather cycle, with sublimation from one region and snowfall on another part of Pluto.

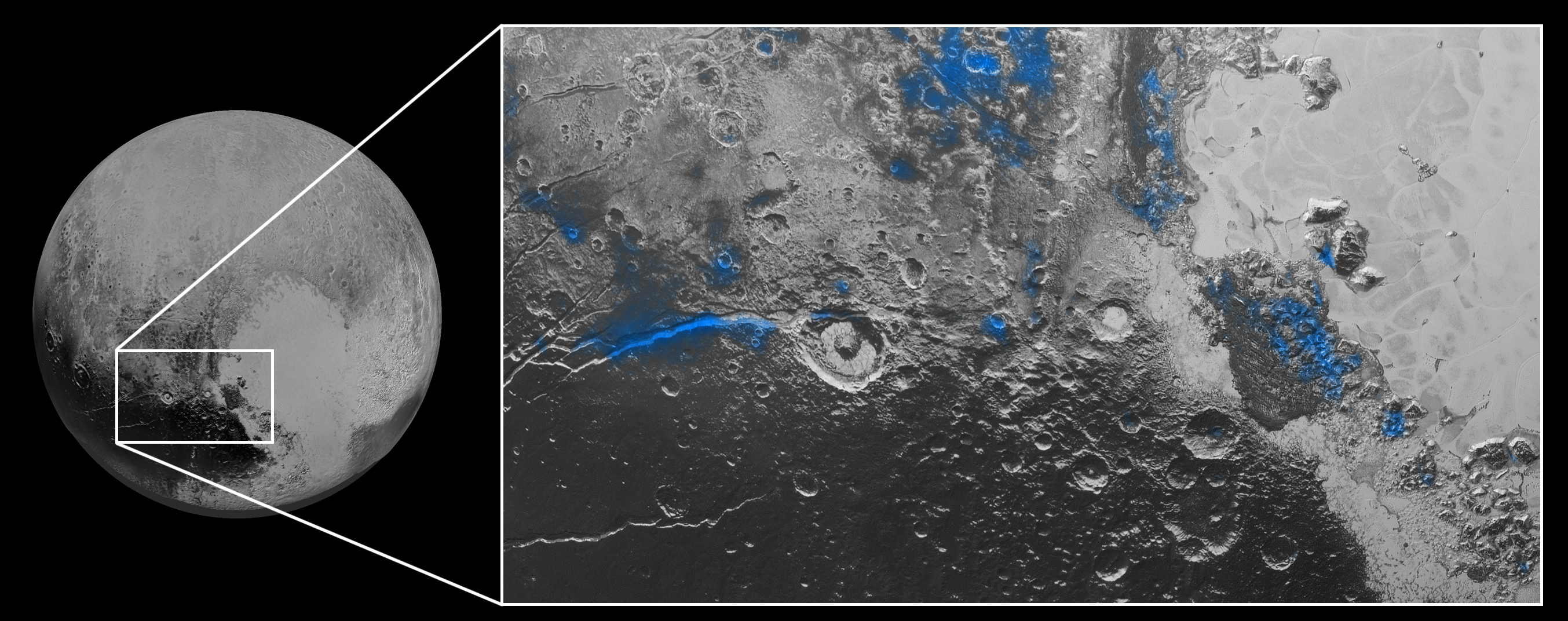

Spectral data recently returned from New Horizons gives scientists a taste for the composition of Pluto’s surface, revealing patches of water ice centered on highlands, mountain peaks, craters, valleys and other regions with rough topography. The smoother plains of Sputnik Planum, with its glacial-like flows, are likely made mostly of frozen nitrogen and methane.

“Large expanses of Pluto don’t show exposed water ice because it’s apparently masked by other, more volatile ices across most of the planet,” said James Cook, a New Horizons science team member from SWRI, in a NASA press release. “Understanding why water appears exactly where it does, and not in other places, is a challenge that we are digging into.”

Comparing the spectral data with images of Pluto shows the water ice locations match areas that appear primarily red in color.

“I’m surprised that this water ice is so red,” says Silvia Protopapa, a science team member from the University of Maryland, College Park. “We don’t yet understand the relationship between water ice and the reddish tholin colorants on Pluto’s surface.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.