A new space weather observatory launched in February has completed a four-month journey to an operating post a million miles from Earth, NOAA announced Monday.

The $340 million mission will look for bursts of particles coming from the sun in the solar wind, giving forecasters warning of solar storms that could disrupt radio communications, electrical grids, satellite operations and air travel.

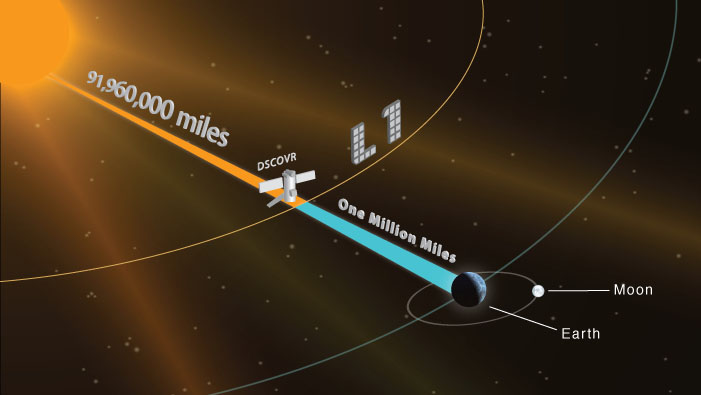

The Deep Space Climate Observatory blasted off Feb. 11 on top of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, beginning a journey to the L1 Lagrange point, a gravitationally-stable location a million miles from Earth in line with the sun.

Since its launch from Cape Canaveral, DSCOVR has deployed its power-generating solar panels and extended a mechanical boom holding the spacecraft’s primary solar wind detector.

DSCOVR arrived Sunday and entered a looping halo orbit around L1, where it will complete final instrument checks before entering service as soon as July. Once operational, DSCOVR will be the first U.S. weather satellite in deep space.

NOAA expects the mission to last at least two years, and DSCOVR carries enough fuel to function for five years.

The observatory’s instruments will monitor the constant stream of the solar wind, providing notice of activity that could generate solar storms.

“DSCOVR will trigger early warnings whenever it detects a surge of energy that could cause a geomagnetic storm that could bring possible damaging impacts for Earth,” said Stephen Volz, assistant administrator for NOAA’s satellite and information service, in a statement.

The mission had to wait nearly two decades since its inception after the project became tied up in political wrangling in Washington.

First proposed by then-Vice President Al Gore in 1998, the mission was supposed to broadcast live views of Earth from a distant vista a million miles away for live streaming on the Internet. Gore believed the mission — which Gore named Triana after one of the sailors on Columbus’s 1492 voyage to the new world — would raise awareness of environmental issues, and scientists developed instruments to collect data on the planet’s climate.

But Republican lawmakers decried the mission as Gore’s pet project, and Congress ordered NASA to stop work on Triana in late 1999. The space agency transferred the nearly-complete satellite into storage in November 2001 after President George W. Bush took office.

NASA formally canceled the mission in 2005 after renaming Triana as DSCOVR. The space agency said the spacecraft, which was originally designed to launch on the space shuttle, could not fit on one of the shuttle’s remaining missions.

NOAA took charge of the mission to replace NASA’s aging Advanced Composition Explorer, which launched in 1997 and is operating well beyond its design life. ACE supplies early warning data on brewing solar storms.

The U.S. Air Force also signed on to the project, agreeing to pay $97 million for DSCOVR’s launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. The Air Force will use the space weather data for military purposes.

“DSCOVR will serve as our tsunami buoy in space, if you will, giving forecasters up to an hour’s warning of these huge magnetic eruptions from the sun that occasionally occur, called Coronal Mass Ejections, or CMEs,” said Tom Berger, director of NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center in Boulder, Colorado, before the mission’s Feb. 11 launch.

Berger’s team will use DSCOVR data to produce space weather forecasts to better predict which areas of Earth could be impacted by a solar storm.

DSCOVR was already fitted with the instruments to detect fluctuations in the intensity, direction, velocity and temperature of the solar wind. The satellite still has the camera and radiometer to take pictures of Earth and track the planet’s energy budget.

Scientists hope the Earth science payload, which is operated by NASA and is now considered a secondary objective behind DSCOVR’s solar wind detection role, will help sort out how much of the sun’s energy is reflected back into space. The data point could help researchers determine how much humans contribute to Earth’s changing climate.

The door to DSCOVR’s Earth-viewing camera was expected to open some time after the satellite’s arrival at L1. Its first views of Earth should be released in the coming weeks.

The imager will take a full-color picture of the sunlit side of Earth every four-to-six hours, and NASA plans to post the imagery on a public website.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.