Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s small Lunar Flashlight spacecraft, sent to the moon last year to search for water ice deposits at the lunar south pole, will not be able to complete its science mission after a problem with the probe’s propulsion system.

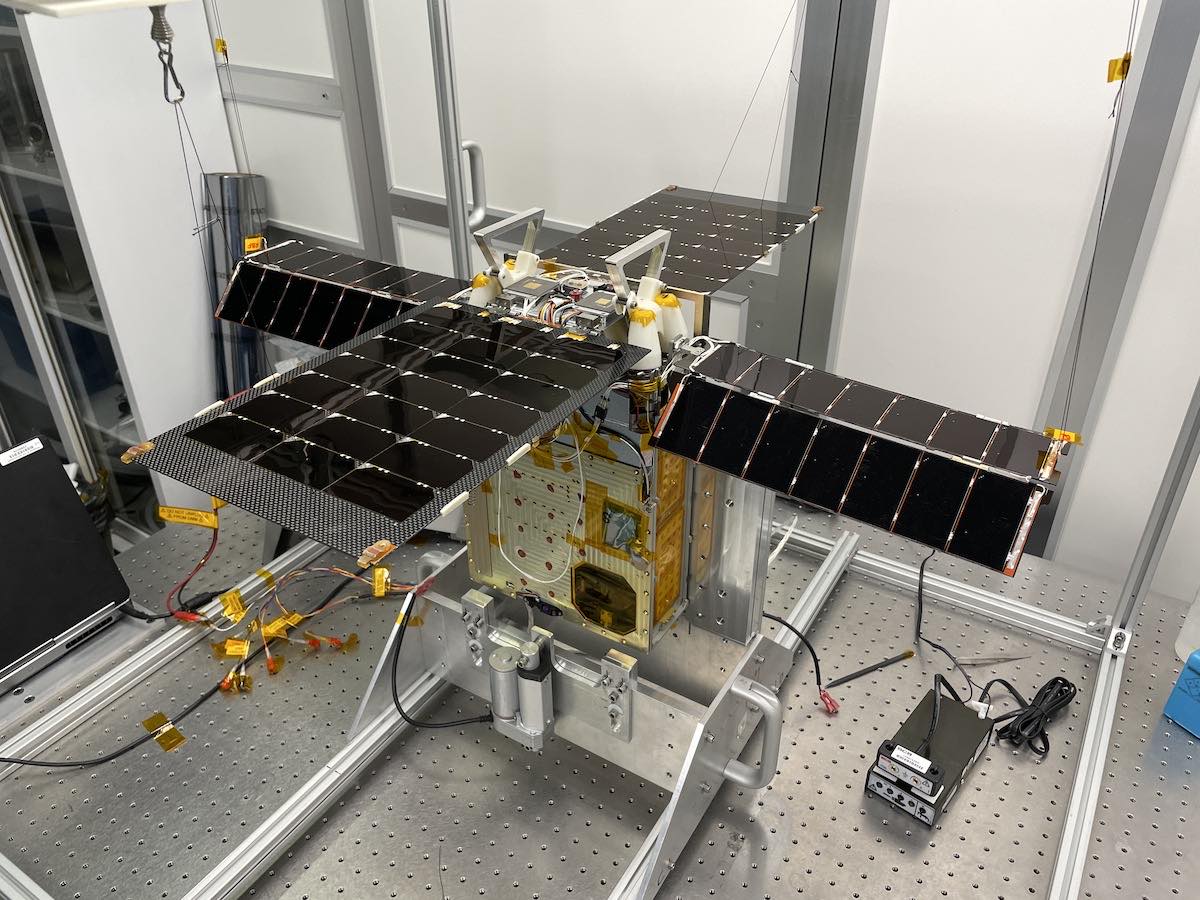

The briefcase-size spacecraft was developed partially as a technology demonstration mission. NASA said May 12 that a new low-power, radiation-hardened flight computer and an upgraded radio, with added precision navigation capability for deep space, performed well on the Lunar Flashlight spacecraft, retiring risk so the technology can be used on future small spacecraft missions.

But another novel technology on Lunar Flashlight ran into problems. The propulsion system, with four tiny thrusters, was unable to generate enough power to steer Lunar Flashlight into orbit around the moon, leaving the mission unable to accomplish its scientific objectives.

“There were a number of different technologies on there, which all worked except the thrusters,” said Jim Reuter, associate administrator of NASA’s space technology mission directorate.”

Engineers believe debris accumulated in the spacecraft’s fuel lines prevented its thrusters from generating consistent thrust. Ground controllers developed a way to get reliable thrust out of one of the thrusters by increasing fuel pump pressure far beyond the system’s operational limit, while opening and closing the system’s valves. But the same procedure failed to get consistent performance from the other three thrusters.

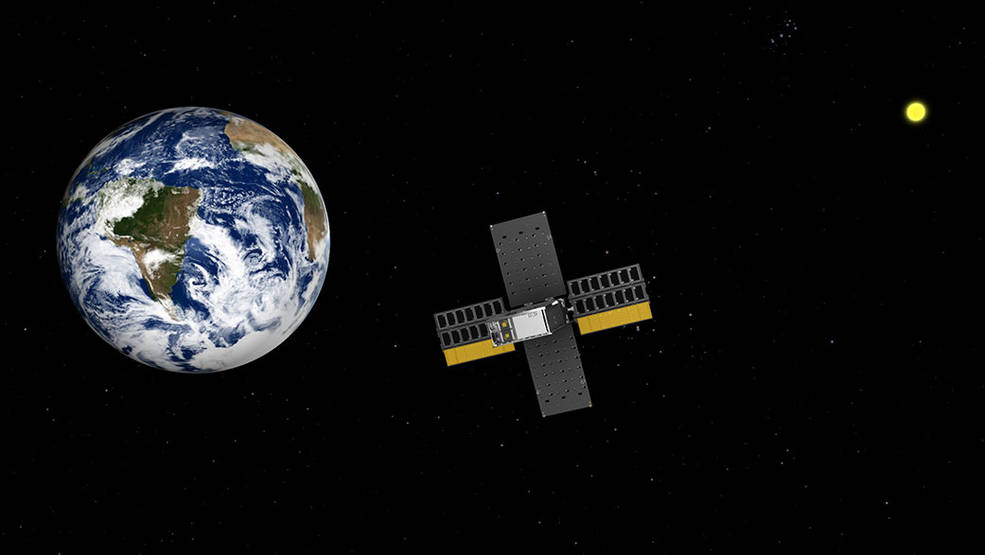

Ground teams needed to maneuver the Lunar Flashlight spacecraft last week to have a chance of getting the spacecraft on a trajectory to make close flybys of the moon’s south pole, where the craft would have shined lasers into permanently shadowed craters to measure the quantity and composition of water ice hidden on dark crater floors. Previous space missions have found evidence of subsurface ice, and hints of water ice deposits at the surface at the bottoms of craters.

“They made some progress, but they just didn’t have enough time, and the clock ran out,” Reuter said Tuesday in a presentation to the NASA Advisory Council’s technology, innovation, and engineering committee.

Lunar Flashlight, managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, would have attempted to confirm the presence of ice at the lunar surface, where water resources could be accessible to future astronauts to create drinking water and rocket propellant.

“It’s disappointing for the science team, and for the whole Lunar Flashlight team, that we won’t be able to use our laser reflectometer to make measurements at the moon,” said Barbara Cohen, the mission’s principal investigator at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “But like all the other systems, we collected a lot of in-flight performance data on the instrument that will be incredibly valuable to future iterations of this technique.”

Lunar Flashlight launched Dec. 11 from Cape Canaveral on top of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, riding as a piggyback payload on the same launcher as the privately-developed Hakuto-R lunar lander from the Japanese company ispace. The Hakuto-R lander crashed on the moon April 25 after running out of fuel in the final moments of descent, according to ispace.

The original flight plan for Lunar Flashlight called for the 31-pound (14-kilogram) spacecraft to enter an oval-shaped orbit around the moon in April that would have taken the spacecraft as close as 9 miles (15 kilometers) from the lunar surface once per week. With time running out, engineers developed a backup plan to steer Lunar Flashlight into a high orbit around the Earth that would take the spacecraft near the moon’s south pole with lower frequency.

In the end, without the propulsion system producing consistent thrust, Lunar Flashlight will leave the Earth-moon system and head into interplanetary space, ending the possibility of it achieving its scientific objectives.

“Technology demonstrations are, by their nature, higher risk and high reward, and they’re essential for NASA to test and learn,” said Christopher Baker, program executive for small spacecraft technology at NASA Headquarters in Washington, in a press release. “Lunar Flashlight was highly successful from the standpoint of being a testbed for new systems that had never flown in space before. Those systems, and the lessons Lunar Flashlight taught us, will be used for future missions.”

Lunar Flashlight was previously assigned to launch on the first flight of NASA’s huge Space Launch System moon rocket. NASA selected 13 CubeSat missions, including Lunar Flashlight, to ride on the first SLS flight, known as Artemis 1.

A NASA spokesperson said in 2021 that issues with the original propulsion system for the Lunar Flashlight spacecraft, a solar sail, forced managers to switch to an alternative design using non-toxic “green” propellant. That slowed development of the mission, and coupled with effects from the COVID-19 pandemic, prevented the spacecraft from being ready for integration with the Artemis 1 rocket.

The propulsion system on Lunar Flashlight was supplied by California-based VACCO Industries, with an ionic liquid-based fuel blend based on the oxidizer ammonium dinitramide, produced by Eurenco Bofors in Sweden. The thrusters were manufactured by the Swedish company Bradford ECAPS.

After missing its ride on Artemis 1, Lunar Flashlight was assigned to launch on a SpaceX rocket with a commercial moon lander owned by Houston-based Intuitive Machines. That launch has been delayed to 2023 due to delays in developing Intuitive Machines’ lander, so NASA was able to switch Lunar Flashlight to the Hakuto-R mission for liftoff in December.

NASA is studying the possibility of a replacement for Lunar Flashlight to pursue the mission’s original science goals, according to Reuter.

“We’ll be looking at what it would take to repeat the mission because we really want to send that message, when there’s something that doesn’t go right, let’s figure out a way to update it next time,” Reuter said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.