Rocket Lab said Saturday that the company received final approval from NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration to launch their first mission from the United States on Sunday, clearing final regulatory and technical hurdles with a new autonomous range safety destruct unit that delayed the launch more than two years.

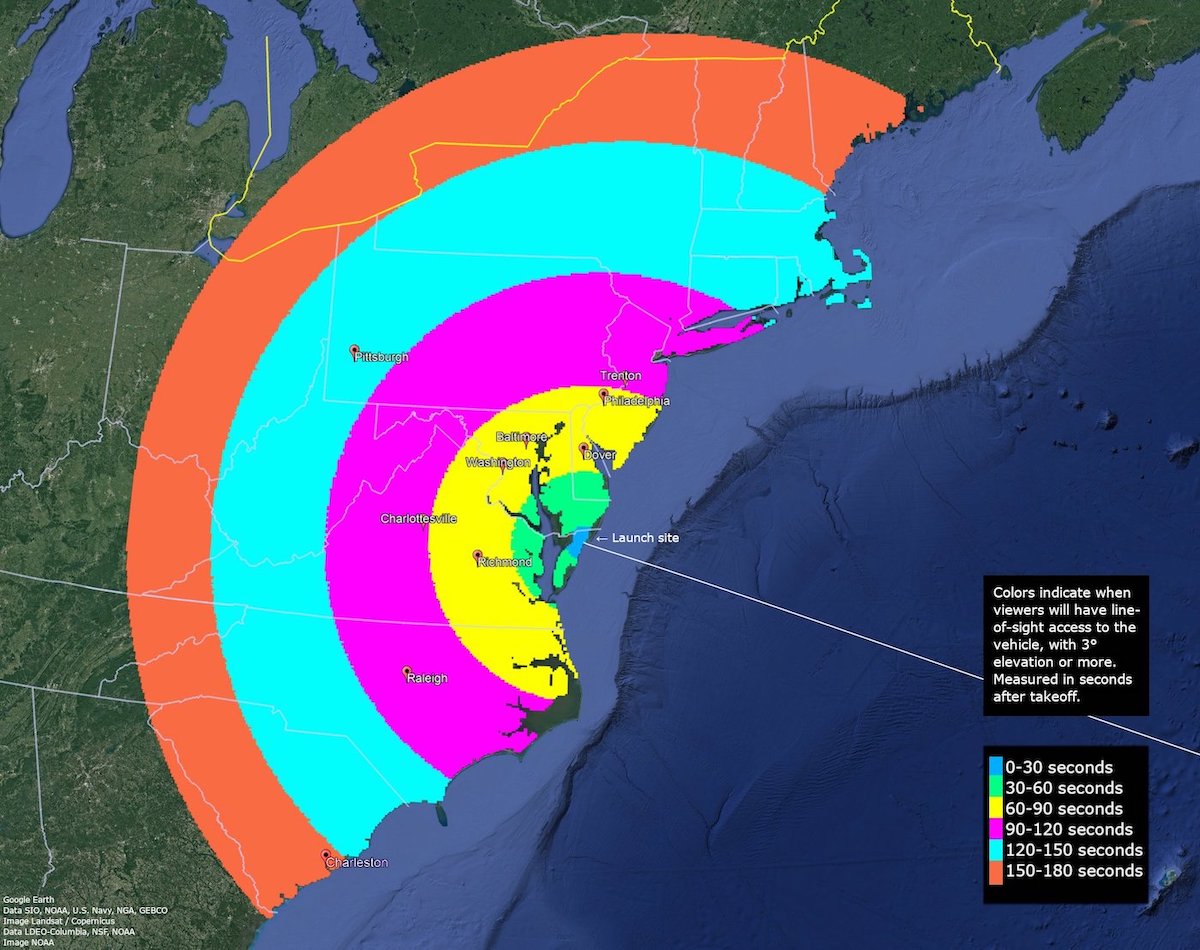

There is a two-hour launch window Sunday, opening at 6 p.m. EST (2300 GMT), for liftoff of Rocket Lab’s Electron booster from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport on Wallops Island, Virginia. Forecasters at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility predict a 90% chance of favorable weather for launch Sunday, with only a slight concern for thick clouds.

Rocket Lab and NASA range teams will monitor high-altitude winds during Sunday’s countdown to ensure conditions in the upper atmosphere will permit the Electron rocket to safely climb into space with three small satellites for HawkEye 360, a U.S. company building a satellite constellation to detect and locate the source of terrestrial radio signals.

Rocket Lab has its corporate headquarters in Southern California, and operates two rocket factories in California and in New Zealand. The company’s Electron rocket has flown 32 times since 2017 from a privately-owned spaceport on the North Island of New Zealand, delivering 152 satellites to orbit on 29 successful missions.

“The final licensing paperwork for launch is complete and we are 100% go for launch tomorrow,” tweeted Peter Beck, Rocket Lab’s founder and CEO, on Saturday evening. “Huge thanks to NASA Wallops and the FAA. Time to fly, this time from the northern hemisphere.”

Rocket Lab says the Electron launcher and its three commercial satellite payloads are ready for blastoff. The launch was delayed from Friday to wait for final certification of the rocket’s autonomous flight termination system software. The Rocket Lab mission from Virginia will be the first space launch to use a NASA-developed customizable flight safety system designed to provide autonomous flight termination capability to a range of different commercial launch vehicles.

Other companies, like SpaceX, have developed proprietary autonomous flight termination systems for use on their own rockets. The NASA Autonomous Flight Termination Unit, or NAFTU, can be adopted by multiple launch service providers.

But software problems with the NAFTU system delayed the debut of Rocket Lab in Virginia more than two years.

“I have to say it feels great to be at this point,” Beck said Dec. 14 in a pre-launch press briefing. “Obviously, it’s been a long road. We built the launch site around about three years ago. It was a super-quick build, but … there have been lots of challenges along the way with AFTS (Autonomous Flight Termination System) and COVID, and all the rest of it, but I’m very pleased to say that today we’re all done, which is great. The rocket is ready, it’s on the pad. The team is ready, and it’s time to fly.

“This flight just doesn’t just symbolize another launch pad for Rocket Lab,” Beck said. “It’s the standing up a new capability for the nation. It’s a new AFTS system being brought online for the industry, and it’s a new rocket to Virginia and to the Wallops Flight Facility.”

NASA developed the NAFTU system in partnership with the U.S. military and the FAA. It’s designed to help streamline rocket operations from Wallops and other launch ranges around the country.

David Pierce, director of NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility, said the rocket-agnostic autonomous flight termination system will help enable “responsible launch capability for the United States.”

“It’s been nothing short of a herculean effort to get us to this point, which I view as a turning in launch range operations, not just at Wallops but across the United States,” Pierce said. Eighteen companies have requested access to the NAFTU software code to merge it with their launch vehicles.

Rocket Lab uses the NAFTU software in a flight termination system system it calls Pegasus. Pierce said NASA has verified Rocket Lab meets all of the agency’s range safety criteria to launch from Wallops, located on Virginia’s Eastern Shore.

NASA hoped to have the NAFTU software ready for Rocket Lab to launch its first mission from Virginia in mid-2020. But Pierce said engineers “discovered of a number of errors in the software code” during validation testing. NASA partnered with the Space Force and FAA to fix the software.

“The certification process painfully took well over a year to develop the test procedures and all of the script that you would need to go with that software to ensure that it was safe to operate,” Pierce said. “In 2022, we were in a process where we began independent certification testing.”

Engineers finished independent testing of the NAFTU software over the summer, then completed independent certification of the system in October, according to Pierce. That allowed NASA to hand over the software code to Rocket Lab, which modified it for integration onto the Electron launch vehicle.

According to Pierce, the FAA asked NASA to complete a risk assessment report before giving final approval for the launch. “NASA is fully confident in Rocket Lab’s and NASA’s safety plans,” Pierce said.

A flight termination system is a standard part of all space launches from U.S. spaceports, ensuring that a rocket can be destroyed if it veers off course and threatens populated areas after liftoff. With autonomous flight termination systems, range safety teams no longer need to be on standby to send a manual destruct command to the rocket.

Pierce said the automated system lowers the cost of launch operations. Range teams at Cape Canaveral have said the introduction of autonomous flight termination systems by SpaceX allows for rapid turnaround between launches, reducing the previous two-day stand-down between rocket missions to less than an hour. The Space Force range team in Florida was ready to support two back-to-back launches of Falcon 9 rockets Friday just 33 minutes apart, but SpaceX delayed one of the missions to prioritize the other.

The NAFTU works by tracking the rocket’s location using GPS signals, and then issuing a destruct command if it determines the rocket is outside of a predetermined safety corridor. Rocket Lab has used a similar automated flight termination system for most of its launches from New Zealand.

“The NAFTU system is going to enable launch companies, venture class smaller launch companies, to come at Wallops and be able to launch at an increased cadence, but also enable lower cost launch operations,” Pierce said. “We estimate that this could reduce launch range costs by as much as 30% at our range.”

The Space Force is requiring all rockets launching from military ranges in Florida and California to use autonomous flight termination systems beginning in 2025. United Launch Alliance still uses human-in-the-loop destruct systems, but will transition to automated flight safety technology on the company’s new Vulcan rocket.

Rocket Lab’s launch pad in Virginia, called Launch Complex 2, will give the company three active launch pads, including two facilities at Rocket Lab’s New Zealand spaceport and one at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport.

The new Electron launch pad in Virginia is designed to support up to 12 launches per year, including “rapid call-up” missions, giving the military a quick-response launch option, Rocket Lab said when construction was completed at the new launch complex in 2019.

The Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport is run by the Virginia Commercial Space Flight Authority, or Virginia Space, an organization created by the Virginia legislature to promote commercial space activity within the commonwealth. The spaceport on Wallops Island now has three orbital-class launch facilities, one for Rocket Lab, one for Northrop Grumman’s Antares rocket, and another used to launch solid-fueled Minotaur boosters.

Rocket Lab’s pad sits next to the Antares launch site on Wallops Island.

Beck said the next Rocket Lab mission from Wallops is scheduled for early 2023. The rocket for that flight is scheduled for delivery to the launch site by the end of this year.

Rocket Lab’s hangar at Wallops is designed to accommodate up to three Electron rockets at a time. With its new Virginia launch site online, Rocket Lab says it will have flexibility to move missions between different launch ranges. And some U.S. government customers prefer to launch their payloads from the United States.

Rocket Lab also plans to launch its larger next-generation reusable rocket, called Neutron, from a new launch pad on Wallops Island. The company is building a factory and integration and test facilities for the Neutron program in Virginia, combining manufacturing and operations capabilities at the spaceport on the Eastern Shore.

With the two-and-a-half year delay in beginning launches from Virginia, Rocket Lab had to move the launch of the U.S. military payload originally slated for the first Electron flight from Wallops to the company’s New Zealand spaceport.

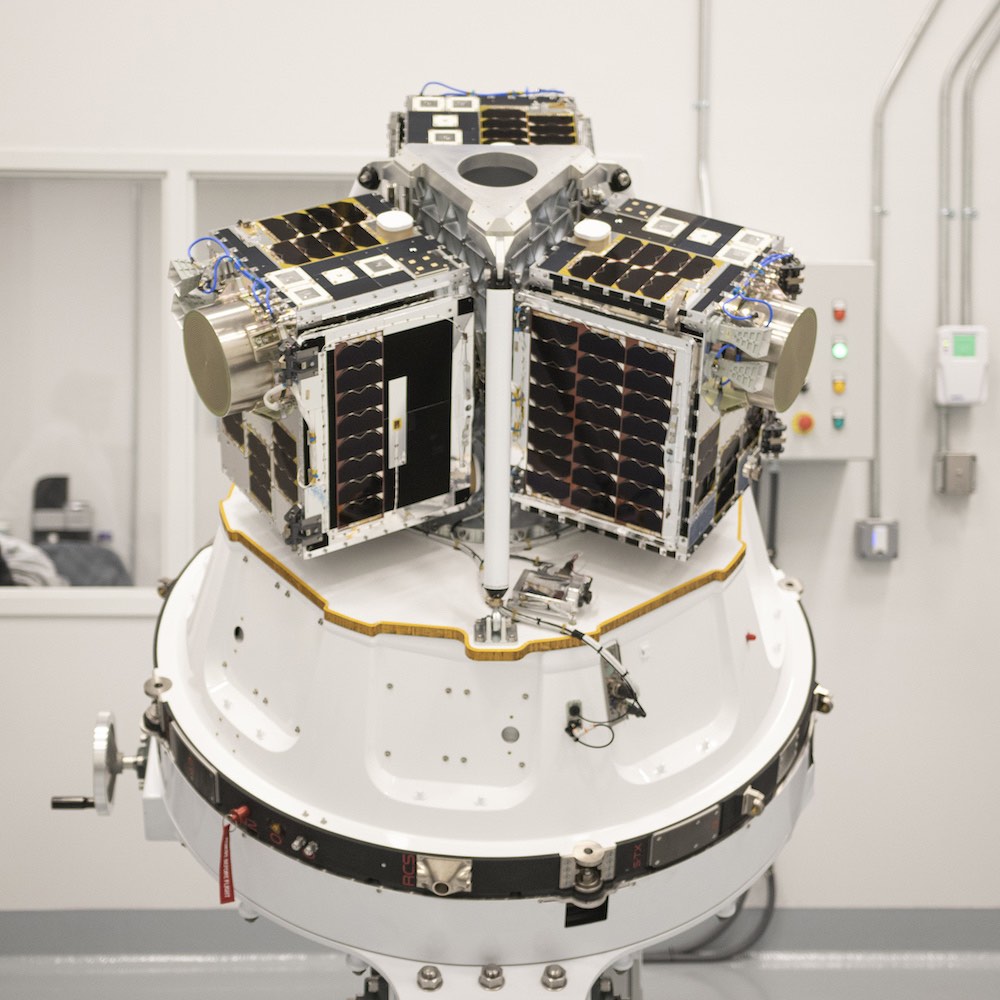

Three microsatellites for HawkEye 360, based in Northern Virginia, will instead ride into orbit on Rocket Lab’s Virginia launch debut.

“We’re proud to be a Virginia-based company, with Virginia-developed technology, launching out of the Virginia spaceport,” said John Serafini, HawkEye 360’s CEO, in a press release. “We selected Rocket Lab because of the flexibility it enables for us to place the satellites into an orbit tailored to benefit our customers. Deploying our satellites on Rocket Lab’s inaugural launch is a giant leap in Virginia’s flourishing space economy.”

The mission will mark the sixth launch of HawkEye 360 satellites, and is the first of three dedicated Rocket Lab missions contracted by HawkEye 360. All of HawkEye 360’s satellites so far have launched on rideshare missions aboard SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets.

HawkEye 360 has launched 12 operational satellites since early 2021, helping detect, characterize, and locate the source of radio transmissions. Such data are useful in government intelligence-gathering operations, combating illegal fishing and poaching, and securing national borders, according to HawkEye 360.

The satellites launching on Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket will be deployed into a 341-mile-high (550-kilometer) orbit at an inclination of 40.5 degrees to the equator. Rocket Lab does not plan to recover the rocket’s first stage booster after liftoff, as it has tried doing following recent launches from New Zealand.

The two-stage, 60-foot-tall (18-meter) Electron launcher will head east-southeast from the launch site in Virginia, powered by nine kerosene-fueled Rutherford engines. The carbon composite rocket’s second stage will take over the mission about two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff to accelerate into a preliminary orbit, then yield to a kick stage for the final maneuver to inject HawkEye 360’s satellites into their final targeted orbit.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.