The James Webb Space Telescope slipped into orbit around a point in space nearly a million miles from Earth Monday where it can capture light from the first stars and galaxies to form in the aftermath of the Big Bang.

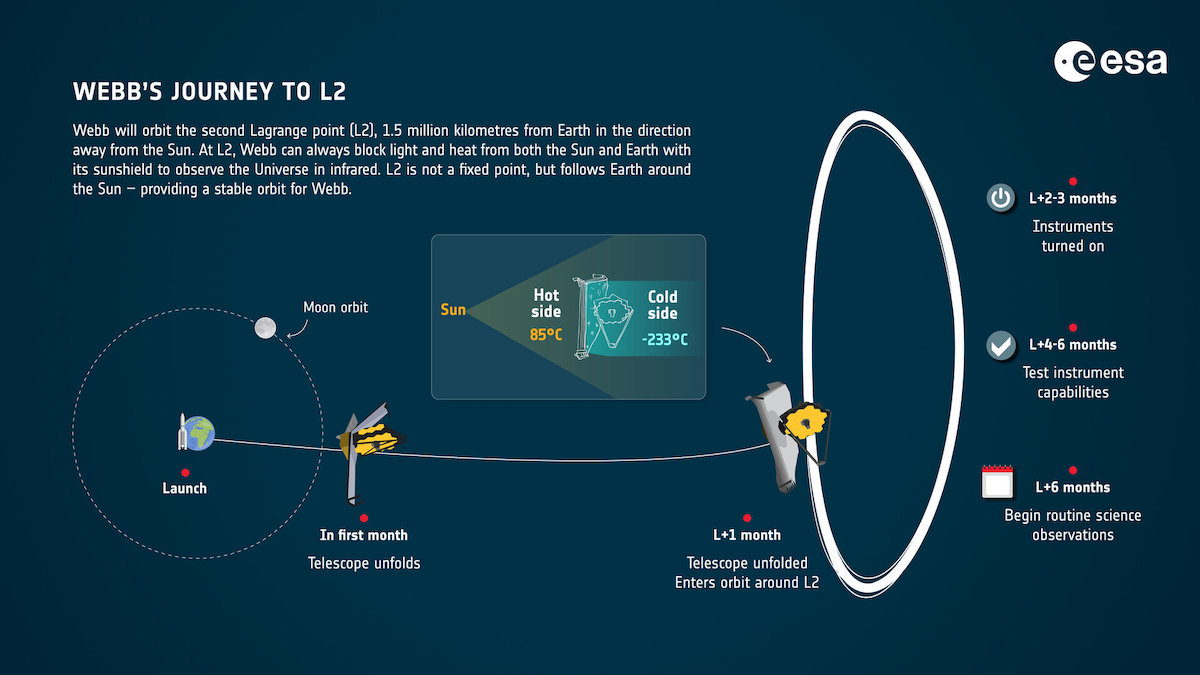

As planned, the European Ariane 5 rocket that launched Webb on Christmas Day put the telescope on a trajectory that required only a slight push to reach the intended orbit around Lagrange Point 2, one of five where the pull of sun and Earth interact to form stable or nearly stable gravitational zones.

The push came in the form of a 4-minute 57-second thruster firing at 2 p.m. EST — 30 days after launch at a distance of 907,530 miles from Earth — that increased Webb’s velocity by a mere 3.6 mph, just enough to ease it into a six-month orbit around L2.

“Webb, welcome home!” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a blog post. “Congratulations to the team for all of their hard work ensuring Webb’s safe arrival at L2 today. We’re one step closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe. And I can’t wait to see Webb’s first new views of the universe this summer!”

Spacecraft at or near L2 orbit the sun in lockstep with Earth and can remain on station with a minimum amount of rocket fuel, allowing a longer operational lifetime than might otherwise be possible.

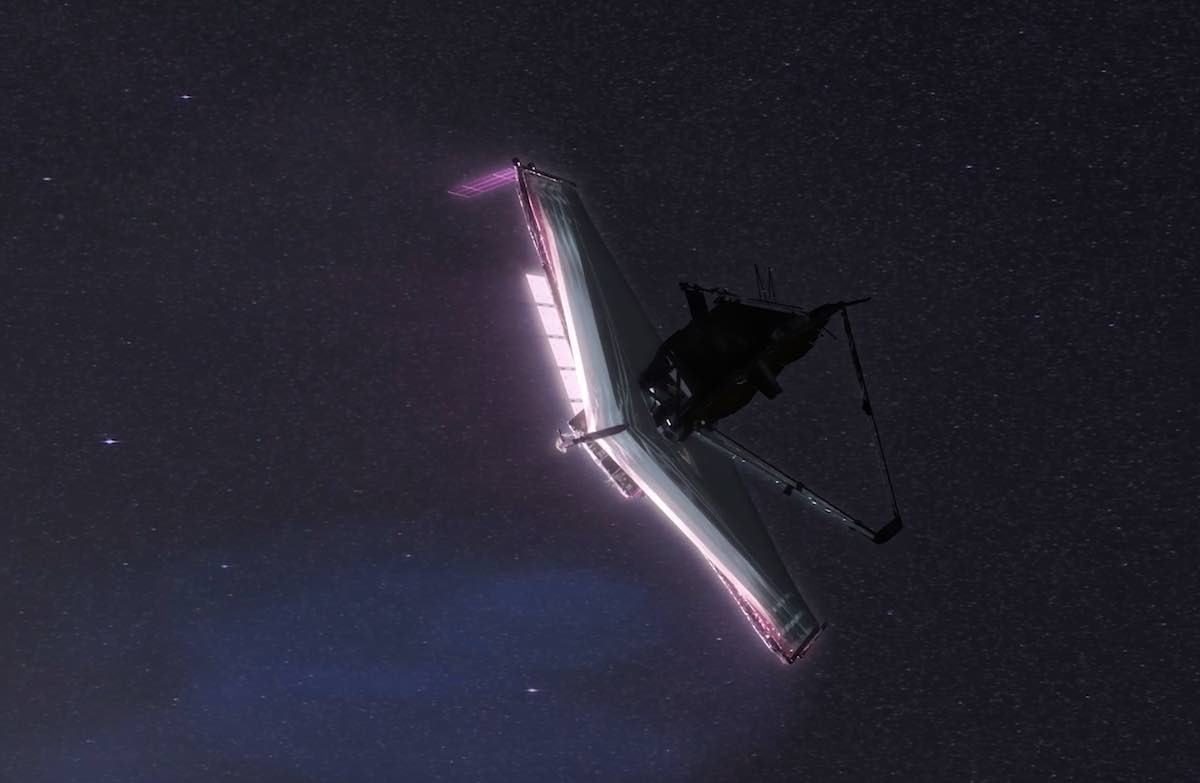

An orbit around L2 also will allow Webb to observe the universe while keeping its tennis court-size sunshade broadside to Earth’s star and the telescope’s optics and instruments on the cold side.

As of Monday, Webb’s mirror had cooled down to minus 347 Fahrenheit, well on the way toward a goal of nearly 390 degrees below zero. That’s what is required for Webb to register the exceedingly faint infrared light from the first stars and galaxies.

For the rest of its operational life, Webb will circle L2 at distances between 155,000 and 517,000 miles, taking six months to complete one orbit. Because the orbit around L2 is not perfectly stable, small thruster firings will be carried out every three weeks or so to maintain the telescope’s trajectory.

“Congrats to the team!” tweeted NASA science chief Thomas Zurbuchen. “@NASAWebb is now in its new stable home in space & one step closer to helping us #UnfoldTheUniverse.”

Before launch, engineers said Webb likely would have enough propellant to operate for five to 10 years. But thanks to the precision of its Ariane 5 launch and two near-perfect trajectory correction burns carried out later, it now appears Webb could remain operational for many years beyond that.

In any case, with the L2 orbit insertion burn behind then, scientists and engineers will focus on aligning Webb’s secondary mirror and the 18 hexagonal segments making up its 21.3-foot-wide primary mirror to achieve the required razor-sharp focus.

Each mirror segment is equipped with seven actuators, six of which can make microscopic changes in a segment’s orientation and one that can push or pull as required to slightly change a mirror’s shape.

As it now stands, the 18 unaligned segments would produce 18 out-of-focus images of the same star. But over the next few months, the positions of each segment will be adjusted in tiny increments, one at a time, to move reflected starlight to the center of the telescope’s optical axis.

Once all 18 light beams are precisely merged, or “stacked,” Webb will effectively be in focus, clearing the way for instrument calibration. The first science images from the fully commissioned telescope are expected this summer.