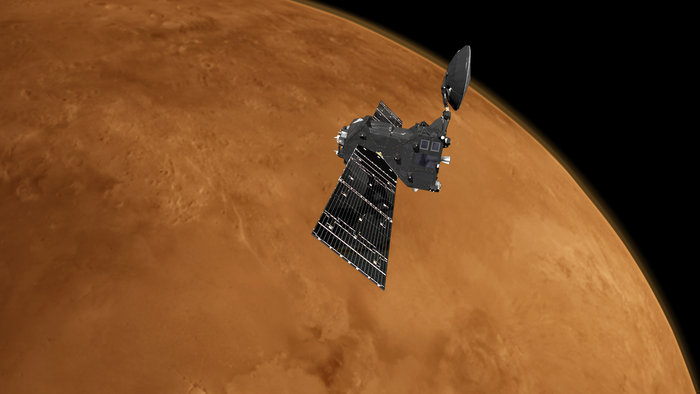

Four of the European Space Agency’s robotic missions, including the agency’s two Mars orbiters, are resuming science operations after a stand-down triggered by the positive diagnosis of an employee at ESA’s control center in Germany with the coronavirus.

ESA said Thursday that the four missions are moving back into normal operations after officials suspended science data-gathering in late March.

Agency managers decided to suspend science operations on the missions after a member of the workforce at the European Space Operations Center, or ESOC, in Darmstadt, Germany, tested positive for the coronavirus.

“This person is thankfully fine, and recovering well,” said Paolo Ferri, head of mission operations at ESOC, in an ESA statement. “However, in the two days at work before he was diagnosed, he came into contact with about 20 colleagues on site.”

ESA says those 20 people went into quarantine, and entire buildings at the operations center were thoroughly cleaned and disinfected.

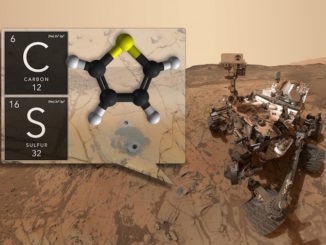

Many of the individuals potentially exposed to the virus worked on the Solar Orbiter mission, which recently launched in February, ESA’s Mars Express and ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, and the Cluster mission, which comprises four spacecraft orbiting Earth.

“We decided to preventatively suspend operations on these missions until the risk of a potential cascade of follow-on infections and quarantines disappeared,” Ferri said in an ESA press release.

None of the people in quarantine have developed symptoms, and ESA has decided to reactivate the four missions. Other satellites in ESA’s fleet, such as astronomy and Earth-observing spacecraft, were not impacted by the coronavirus stand-down.

“Your heart aches every time you have to turn off science, but this is not an exceptional case,” Ferri said. “It happens sometimes that one of these satellites has problems and maybe goes into safe mode, and it takes at least a week before science operations restart.

“This time, stopping science for issues relating it to the health of the people on the ground of course is unique, but you feel even more compelled to do it than when it’s done to save a machine,” he said.

ESOC personnel are working from home as much as possible, and employees who do come to work are typically isolated. If they must be in the same room, ESA says the personnel are following strict social distancing guidelines.

“For the Mars orbiters, of course our heart bleeds every time we aren’t able to do science with them,” said Markus Kissler-Patig, head of science operations at the European Space Astronomy Center in Madrid. “We are really responsible for the scientific output of all these fantastic spacecraft, and that is what we really want to maximize — the science for researchers but also for humankind.”

“But this was about the health of our people, and for us this is a no-brainer,” Kissler-Patig said in an ESA press release. “These decisions are simple to make, because you know it’s the right thing to do.”

Meanwhile, teams at ESOC are readying for the April 10 flyby of the Mercury-bound BepiColombo spacecraft with Earth. BepiColombo is on course for the immovable April 10 encounter, which will use Earth’s gravity to slingshot onto a trajectory that will eventually intercept Mercury for an orbit insertion maneuver in 2025.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.