In a major shift, NASA is considering using two commercial launchers to send an unpiloted Orion crew capsule and its European-built service module on a test flight around the moon next year, maintaining the lunar test flight’s schedule despite fresh delays in the development of the multibillion-dollar Space Launch System that jeopardize the heavy-lifter’s 2020 inaugural flight, the agency’s administrator said in a congressional hearing Wednesday.

The lunar test flight, known as Exploration Mission-1, is a precursor to NASA’s plans to fly astronauts on the Orion spacecraft, build an outpost in lunar orbit, and eventually return humans to the moon’s surface. But Exploration Mission-1, or EM-1, has faced repeated delays as engineers build and test the Orion capsule and the Space Launch System, the heavy-lift rocket originally designed to loft Orion spaceships and astronauts into deep space for the first time since the last Apollo moon mission in 1972.

NASA now believes the Space Launch System will not be ready for the EM-1 test flight by June 2020, the program’s most recent target launch date. Jim Bridenstine, NASA’s administrator, said Wednesday the space agency is weighing alternatives to keep the Orion spacecraft on track for a lunar mission in 2020 to test the capsule’s European-built power and propulsion module, and assess the performance of the crew capsule’s heat shield during blistering re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere from the moon.

“Some of those options would include launching the Orion crew capsule and the European service module on a commercial rocket,” Bridenstine said in a hearing with the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.

Bridenstine said it is important for NASA to stick to its commitment to launch EM-1 by June 2020, and his announcement Wednesday marked the first time a NASA leader has publicly discussed launching the Orion spacecraft’s first lunar mission on a commercial rocket, and not the more expensive government-run Space Launch System.

“Certainly, there are opportunities to utilize commercial capabilities to put the Orion crew capsule and the European service module in orbit around the moon by June of 2020, which was our originally-stated objective, and I’ve tasked the agency to look into how we might accomplish that objective,” Bridenstine said.

NASA is just beginning to study the possibility of using commercial rockets for EM-1. United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4-Heavy rocket launched an Orion capsule on its first orbital mission, known as Exploration Flight Test-1, in December 2014, sending the crew module and a mock-up service module into an orbit ranging as far as 3,600 miles (5,800 kilometers) from Earth before the capsule splashed down in the Pacific Ocean to conclude a nearly four-and-a-half-hour mission.

There are no rockets currently in service capable of sending an Orion spacecraft and its service module around the moon, but Bridenstine said a pair of commercial launches could be substituted for one SLS flight. A fully-fueled Orion spacecraft is estimated to weigh around 57,000 pounds (25,848 kilograms), near the maximum lift capability of an SLS Block 1 rocket — the heavy-lift launcher’s initial configuration — on a lunar trajectory.

Bridenstine announced NASA’s new look at commercial launch alternatives to the Space Launch System after committee chairman Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Mississippi, raised concerns about new SLS delays.

“Here’s what we can do, potentially — again, we’re starting the process now — we could use two heavy-lift rockets to put the Orion crew capsule and the European service module in orbit around the Earth, launch a second heavy-lift rocket to put an upper stage in orbit around the Earth, and then dock those two together to throw around the moon the Orion crew capsule with the European service module,” Bridenstine said. “I want to be clear. We do not have, right now, an ability to dock the Orion crew capsule with anything in orbit. So between now and June of 2020, we would have to make that a reality.”

Wicker reminded Bridenstine that replanning Exploration Mission-1 would be challenging to complete by mid-2020.

“This is 2019,” Wicker said.

“We have amazing capability that exists right now that we can use off-the-shelf in order to accomplish this objective,” Bridenstine responded. “Just a few years ago, we launched an Orion crew capsule into deep space on a commercially-procured rocket. That has already happened. What’s different now is we have this European service module, which is how we have propulsion and life support and all these capabilities that we need to last for a period of time with humans in deep space. We can use off-the-shelf capability to accomplish this objective for EM-1, but not change the direction of the SLS and EM-2.”

Exploration Mission-2 is set to be the first Orion mission with astronauts on-board. The most recent schedule released by NASA projects EM-2 would be ready for launch on the SLS in 2023 on a nine-day trip around the moon and back to Earth.

Since the Orion test flight on the Delta 4-Heavy in 2014, SpaceX has debuted its Falcon Heavy rocket, with more than double the Delta 4-Heavy’s lift capacity to low Earth orbit. SpaceX sold a Falcon Heavy mission sold to the U.S. Air Force last year for $130 million, while ULA says a Delta 4-Heavy mission costs around $350 million.

Neither rocket has the power to send the nearly 29-ton (26-metric ton) Orion spacecraft toward the moon on a single launch.

Exploration Mission-1 is slated to last around 25 days, during which time the Orion spacecraft and its service module would travel to the moon, swing as close as 62 miles (100 kilometers) from the lunar surface, then loop into a more distant orbit around 40,000 miles (70,000 kilometers) from the moon. If NASA sticks to EM-1’s current flight plan, a dual-launch alternative using commercial rockets in 2020 would likely have to use separate launch pads, and likely two different rockets, due to the mission’s relatively short duration.

Bridenstine said NASA intends to decide on the commercial launch option for Orion in the “next couple of weeks.”

“Every moment counts because … NASA has a history of not meeting launch dates, and I’m trying to change that,” he said.

Wicker then asked Bridenstine how much it would cost to move the Orion capsule’s launch to large commercial rockets, which customers typically purchase at least two years in advance.

“That’s another discussion,” Bridenstine replied. “I think there are options to achieve the objective, but it might require some help from the Congress.”

Before addressing the specifics of NASA’s consideration of commercial launchers for the Orion test flight, Bridenstine said in his opening statement Wednesday that NASA must be bold.

“We need to have really impressive goals and stunning achievements that the world can get behind,” he said. “I can tell you, as the NASA administrator, when I meet with our international partners, one of the things that they’re most excited about is the idea that we’re going to go to the moon again.”

EM-1 will be the first Orion flight with a fully functioning service module, built by Airbus Defense and Space and funded by the European Space Agency as an international contribution to NASA’s deep space exploration program. Airbus delivered the service module delivered to the Kennedy Space Center in November for final assembly and testing with the Orion crew capsule.

The service module includes four solar array wings to generate electricity, a U.S.-provided engine left over from the space shuttle program, the Orion spacecraft’s cooling system, and water and air tanks to keep crews alive on the journey to and from lunar orbit.

NASA and European managers say the Orion crew capsule and service module are scheduled to be ready to begin final launch preparations in early 2020. The crew capsule’s heat shield was mated to the spacecraft last year, and the service module was powered on in February for the first time since arriving in Florida.

The two segments will be mated together for the first time in the coming months, and engineers plan to transfer the Orion spacecraft to NASA’s Plum Brook Station in Ohio in July for a battery of tests in a thermal vacuum chamber to verify the ship’s performance in the cold, airless environment of space. The spacecraft will return to Florida around October, according to a schedule released by ESA.

Concerns about the readiness of the European-built service module has previously been a factor in determining EM-1’s launch date, but the element’s delivery to Florida last year was a major milestone in getting the module ready for flight.

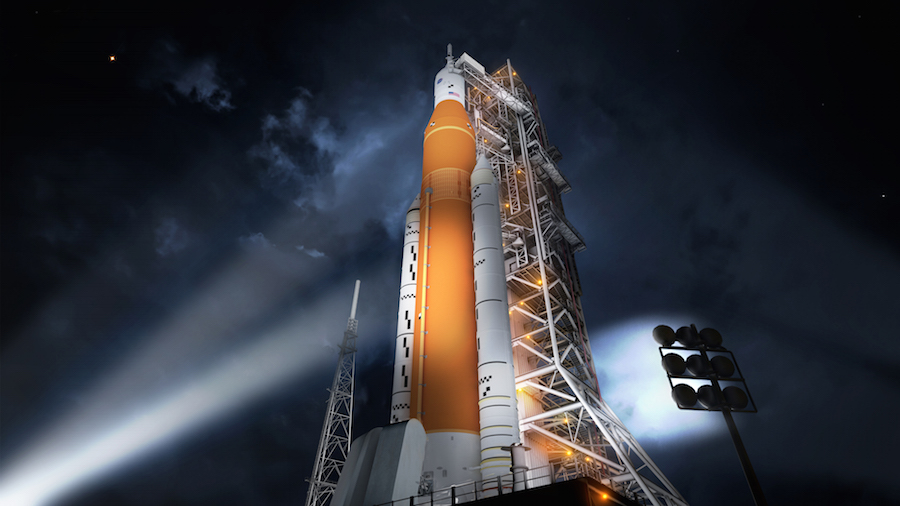

A report in October by NASA’s inspector general criticized the agency and Boeing for cost and schedule overruns on the SLS core stage, which has encountered development problems that previously delayed the first SLS launch date from late 2018 to mid-2020. The core stage will contain liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants feeding four modified space shuttle main engines. Two side-mounted solid-fueled boosters built by Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems, also derived from shuttle-era designs, will provide additional thrust.

The SLS Block 1 rocket will also have an upper stage derived from ULA’s Delta 4 rocket, with a single Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10 engine.

Other than the core stage, most hardware for the first Space Launch System remains on track for a 2020 launch, including the main engines, the solid rocket boosters and the upper stage.

The Trump administration’s $21 billion fiscal year 2020 budget request for NASA released Monday would defer the development of a bigger four-engine upper stage for the Space Launch System’s Block 1B configuration. NASA intended the more powerful SLS Block 1B to launch co-manifested missions with Orion crew capsules and modules for the agency’s planned Gateway, a mini-space station in the vicinity of the moon envisioned as a waypoint for landers traveling to and from the lunar surface.

Instead, NASA officials said Monday they plan to launch elements of the Gateway on commercial rockets, decoupling the modules from the Space Launch System.

The White House’s NASA budget request also proposes launching a robotic probe to explore to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa on a commercial rocket, and not with the Space Launch System. In a NASA budget bill passed earlier this year, Congress included language specifying the Europa Clipper mission should launch on the SLS.

Lawmakers led by Sen. Richard Shelby, R-Alabama, chairman of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee, have long supported the Space Launch System. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, is home to the SLS program.

Congress approved $2.15 billion for the Space Launch System program in fiscal year 2019, while the Trump administration’s budget request would slash that by $375 million to around $1.78 billion.

Shelby said last week that, in his role as chairman of the appropriations committee, he has “more than a passing interest in what NASA does,” according to a report in Space News.

“I have a little parochial interest, too, in what they do in Huntsville, Alabama,” Shelby continued in an introduction of Marshall center director Jody Singer at a luncheon in Washington. “Jody, you keep doing what you’re doing. We’ll keep funding you.”

In his remarks Wednesday, Bridenstine said the Space Launch System remains a “critical piece” of NASA’s deep space exploration plans.

“We’re talking a rocket that has a throw weight larger than anything we’ve ever been able to throw before,” Bridenstine said of the Space Launch System. “We’re talking about a rocket that’s larger than the Statue of Liberty, with a fairing size that can put really big objects into space, and in fact, into deep space, in orbit around he moon, even. It is a critical capability.

“Now, here’s the challenge that we have with EM-1. SLS is struggling to meet its schedule. It was originally intended to launch in December of 2019 (and) no later than June of 2020. We are now understanding better how difficult this project is, and that it’s going to take some additional time.”

It was not immediately clear from Bridenstine’s statement Wednesday whether NASA would consider putting astronauts on EM-2, which would become the first launch of the SLS under the scenario outlined Wednesday. NASA has avoided flying a crew on the inaugural launch of a new spacecraft or rocket since the first space shuttle mission.

Bridenstine later clarified to reporters that NASA could still put astronauts on EM-2 without an uncrewed SLS test launch, according to Space News.

The Space Launch System’s Boeing-built core stage will undergo a full-duration test-firing, or “green run,” at NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi with its four RS-25 main engines before launching for the first time from the Kennedy Space Center.

“The key is we want to test fully the Orion crew capsule and the European service module around the moon, and then ultimately maintain the SLS program, so that by the time we do EM-2, it will have done a full-up green run test … and then, after the green run test, we will have tested the SLS, we will have tested the Orion crew capsule and the European service module around the moon, and then we can get back on track for EM-2,” Bridenstine said. “The goal is to get back on track.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.