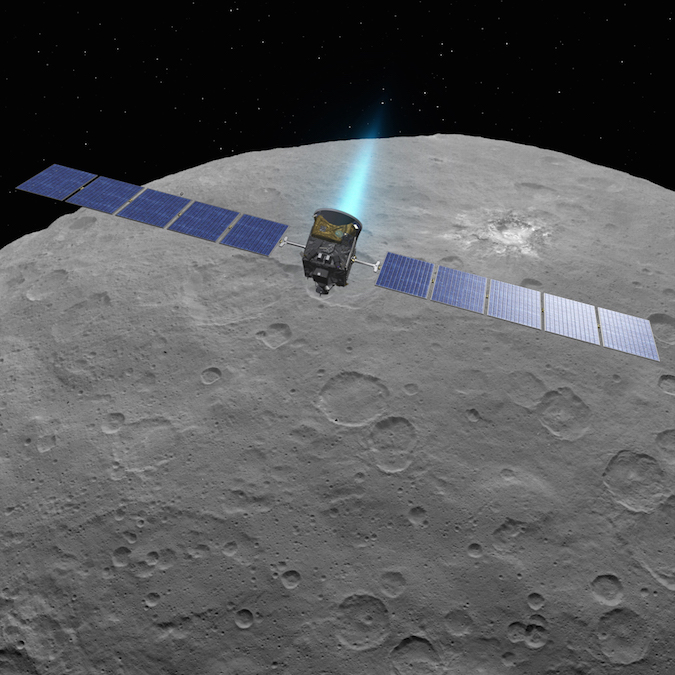

In the closing months of a nearly 11-year mission, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft has arrived in its final orbit around the dwarf planet Ceres and is obtaining the sharpest views yet of the king of the asteroid belt.

Dawn switched off its ion engine June 6 after reaching an elliptical orbit taking the spacecraft as close as 22 miles (35 kilometers) from Ceres on each 27-hour loop. At its highest point, the orbit takes Dawn to a distance of around 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers).

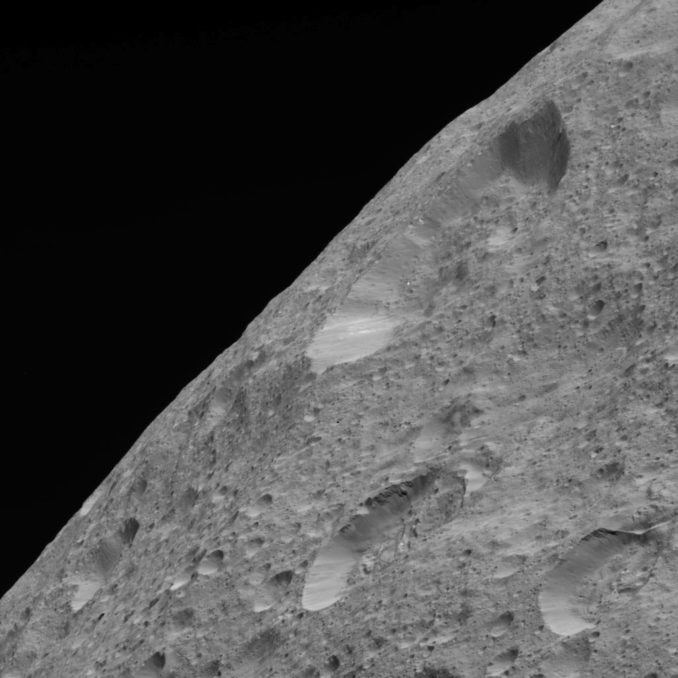

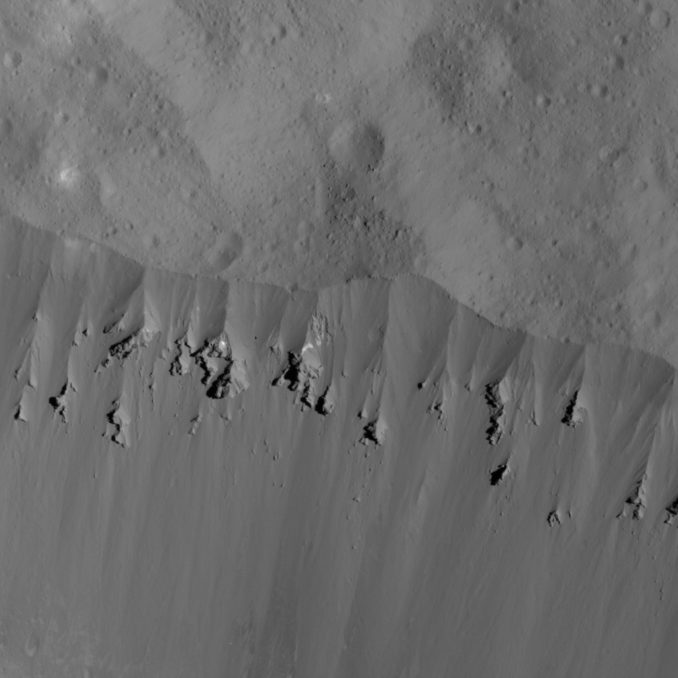

The spacecraft is now flying 10 times closer to Ceres than ever before, allowing its science instruments to better resolve surface features and composition, with the new orbit designed to take Dawn low over Occator Crater, where bright salt deposits have garnered the attention of scientists and space enthusiasts.

Dawn is running low on hydrazine maneuvering propellant, and the spacecraft can no longer rely on spinning momentum wheels for pointing, but engineers stretched out the probe’s fuel lifetime to get an extra two years of science observations at Ceres.

NASA last year approved a final mission extension, and planners at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory crafted a new trajectory to take Dawn closer to Ceres. A series of ion engine burns, using electrically-charged xenon to continuously generate low levels of thrust for weeks at a time, guided Dawn into the lower orbit over the past few months.

Dawn paused in an intermediate orbit to take detailed images and infrared spectra of Ceres’ southern hemisphere in summer, when sunlight shines brighter. The improved illumination, and greater spectral coverage, will allow scientists to better compare the southern hemisphere with Ceres’ northern regions, which Dawn observed in summer earlier in the mission.

The Dawn spacecraft is the first to visit Ceres, which was previously studied exclusively through telescopes. Dawn arrived at Ceres in early 2015 after orbiting the giant asteroid Vesta in 2011 and 2012, making the robotic mission the first to orbit two objects in the solar system besides the Earth and the moon.

Ceres is the biggest object in the asteroid belt, a zone between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Measuring about 590 miles (950 kilometers) across, Ceres is about 40 percent the size of Pluto but comprises about one-quarter of the total mass of the objects in the asteroid belt.

The dwarf planet orbits the sun in a slightly elongated orbit, and it reached the closest point to the sun — called perihelion — in its 4.6-year-long year in April 2018 at a distance of around 238 million miles (383 million kilometers).

Dawn will consume more of its life-limiting hydrazine fuel in its new orbit. The spacecraft relies on its hydrazine-fueled thrusters to keep its instruments pointed at Ceres, and faster passages over the dwarf planet at low altitude require more propellant usage.

Three of the solar-powered craft’s four rotating reaction wheels, which pointed the probe using momentum, failed earlier in the mission, leaving Dawn’s rocket jets as the only means to control its orientation.

Dawn’s ultra-efficient xenon-fueled ion engines produce little thrust, and are used for large orbit adjustments, not for fine pointing.

After arriving in its new perch, Dawn resumed science observations June 9. The spacecraft has already beamed its first images from the low-altitude orbit back to Earth.

Dawn was built by Orbital ATK — now part of Northrop Grumman — and launched from Cape Canaveral in September 2007 aboard a Delta 2 rocket with nearly 100 pounds (45 kilograms) of hydrazine fuel in its 12-gallon (45-liter) tank.

Ground controllers do not know exactly how much propellant remains in Dawn’s tank because fuel measurement on-board spacecraft are imperfect. Engineers have tracked propellant usage by carefully cataloging every thruster firing and subtracting the estimated fuel burned from the quantity loaded into the spacecraft before launch.

Using the subtraction method, engineers have calculated that around 1.8 gallons (7 liters) of hydrazine are left in Dawn’s tank. But there is still some uncertainty in that estimate, and nearly a liter of Dawn’s hydrazine is classified unusable once pressures inside the craft’s propulsion system drop too low to push the fuel the probe’s 12 small rocket thrusters.

Taking into account all the uncertainties, engineers say Dawn likely has enough hydrazine to keep the spacecraft going for three months in its new orbit, meaning the mission will most likely end in September. But it could be August or October, according to Marc Rayman, Dawn’s mission director and chief engineer at JPL.

“The team will continue to guide Dawn in squeezing as much out of its time at Ceres as possible, acquiring new data until the spacecraft is unable to comply because it has expended the last puff of hydrazine,” Rayman wrote in a May 31 blog post on JPL’s website.

Once Dawn is out of fuel, its power-generating solar panels no longer point toward the sun, and its high-gain antenna will lose its lock on Earth.

“When the last of the hydrazine is used up, the spacecraft will actuate valves and try to fire thrusters to control its orientation, but hydrazine will no longer flow, so the torque it wants to exert will not be achieved,” Rayman wrote. “The spacecraft will be impotent, its attempts to point correctly futile. The struggle will be brief, as it will soon run out of electrical power, and the central computer will cease operating.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.