The future participation of major segments of Britain’s space industry in Europe’s Galileo navigation system and Copernicus environmental network, two multibillion-dollar flagship programs with dozens of satellites, is sure to be a significant part of negotiations as the UK withdraws from the European Union, according to a member of the European Commission.

European officials want to rely on producers within the European Union for the block’s major programs, according to Elżbieta Bieńkowska, the European Commission’s senior space official.

Britain’s departure from the EU could leave some of the country’s space companies locked out of the Galileo and Copernicus programs, officials said.

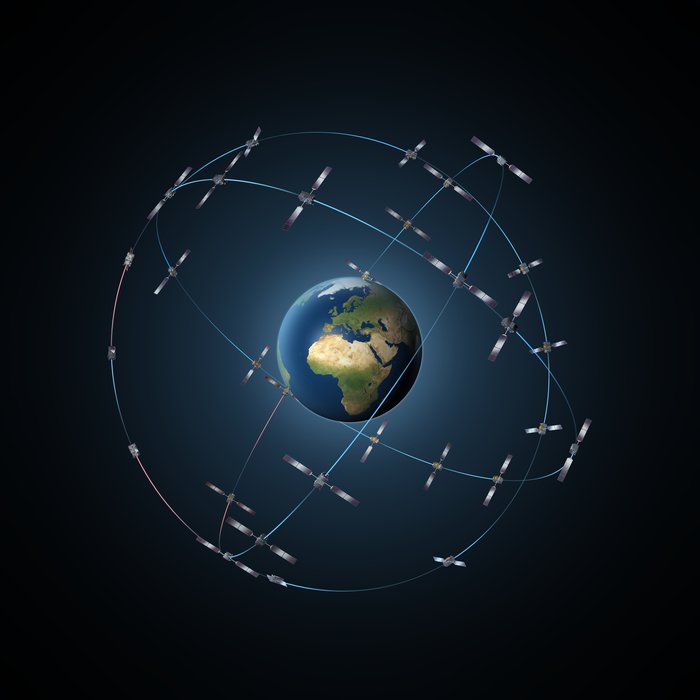

Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd., based in Guildford, England, built 22 navigation payloads for Europe’s Galileo navigation fleet, an analog to the U.S. military’s Global Positioning System. Airbus Defense and Space’s Portsmouth site provided four more navigation payloads, ensuring that at least 26 of the Galileo system’s initial 30-satellite constellation will carry British-built navigation instrumentation.

Britain’s future role in space projects managed by the European Commission, the executive body of the EU, is “one chapter of the negotiations that will be really important for the UK, from their perspective, because they have quite a powerful industry and they participate in our programs,” Bieńkowska said in an interview with Spaceflight Now.

“It’s a huge question mark about this period of negotiations,” said Bieńkowska, the European Commissioner responsible for industry, the internal market and entrepreneurship. “How will it look in the end? This will be one of the most important chapters because they definitely want to stay in the framework of our programs.”

Jan Woerner, ESA’s director general, said British companies will still be eligible to participate in the agency’s projects. While the UK is leaving the EU, Britain’s financial contributions to ESA have increased in recent years, earning industrial contracts to build the spacecraft for the joint U.S.-European Solar Orbiter mission and the ExoMars rover.

The Financial Times reported earlier this week that the European Commission is demanding the right to cancel existing contracts without penalty if a supplier is no longer based in an EU member state. The newspaper also reported the commission is insisting any supplier booted from a EU-managed program should repay the cost of finding a replacement contractor.

SSTL delivered the final Galileo navigation payload under its current contract last year, but Bieńkowska said the European Commission and ESA, which acts as a technical partner and procurement agent for the Galileo program, will buy eight more satellites this year to ensure the constellation is completed by 2020.

“We want to have 30 satellites by 2020, so there’s not much time, Bieńkowska said.

Germany’s OHB built the majority of the Galileo satellites ordered and launched to date in an industrial partnership with Britain’s SSTL.

The contract for the next eight Galileo satellites was supposed to be signed last year, and Brexit negotiations may be partially responsible for delaying the award.

The Financial Times said the European Commission presented the new contract stipulations as a condition for winning work on the eight new Galileo satellites, an award that could be worth up to £400 million, or $500 million, to British industry.

“The clause now threatens to spur a flight of high-tech space companies from the UK, jeopardizing the British government’s ambition to take 10 percent of the £400 billion ($500 billion) a year global space market,” the Financial Times said.

If the European Commission maintains the negotiating stance reported by the Financial Times, Galileo managers will have to look for a new supplier for the satellites’ navigation payloads.

“Executives from two space companies said they were considering whether to relocate their UK activities to EU member states, or to choose different partners in a bid to ensure eligibility for future procurement,” the Financial Times reported.

“We want to rely on European producers,” Bieńkowska told Spaceflight Now.

Britain’s industrial role in the European Commission’s Copernicus program, which will become the world’s largest fleet of environmental satellites, is more limited. But Airbus Defense and Space’s facility in Stevenage, England, is responsible for assembling one of the satellites set for launch later this year, and numerous British companies provide instruments and components on many of the Copernicus program’s polar-orbiting Sentinel spacecraft.

Once the UK is no longer an EU member state, a milestone expected in 2019, the British government must sign a new security accord with the multinational block to access the Galileo system’s encrypted services and receive the satellites’ most precise positioning data. The Galileo network will broadcast open navigation signals to provide positioning data to global users that is more accurate than those offered by the U.S. Air Force’s GPS satellites, according to program officials.

“Since the UK government has so far failed to make any clear statement of intent or even a wish to remain in these important EU space programs, it is not surprising that the EU is cautious about UK industry participation,” Richard Peckham, chair of the trade association UKspace, told the Financial Times.

There are 18 Galileo navigation satellites currently in orbit more than 14,000 miles (23,000 kilometers) above Earth. The launch of the next four Galileo spacecraft on an Ariane 5 rocket has been delayed to at least November as engineers study clock failures on several of the platforms already in space.

The clocks are critical to provide precise positioning data to Galileo’s users, ensuring accurate measurements of the distance between the navigation receiver on the ground and the spacecraft in orbit.

The navigation network works by triangulating a user’s position on the ground by computing the distance between the receiver and multiple satellites.

The signals transmitted by each Galileo satellite include the time they were sent and the orbital position of the spacecraft. Receivers in mobile phones, cars, airplanes and ships can derive their location based on that information.

Another major segment of the European space industry, launchers, is not directly funded by the EU, but Bieńkowska said the European Commission has committed to become an anchor customer for the new Vega-C and Ariane 6 rockets in development for debut flights in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Managed in a cost-sharing public-private partnership between ESA and industry, the new launchers will be cheaper and more capable than Europe’s existing Ariane 5 and Vega boosters. While European officials say the upgraded rockets will get a steady stream of contracts to launch government-backed scientific, navigation, Earth observation and military missions, their place in the commercial launch market will be pressured by SpaceX’s partially-reusable Falcon 9 booster and other vehicles.

“These are the launchers we want to develop, and we will use all of our tools, including procurement, to support them,” Bieńkowska told Spaceflight Now on April 5 after a speech at the 33rd Space Symposium in Colorado Springs.

In her prepared remarks, Bieńkowska endorsed Europe’s launch industry, saying that Europe’s autonomous access to space is a cornerstone of the continent’s security and economy.

“We observe very closely the ongoing revolution in the launcher market, especially here in the United States, around the principle of reusability,” Bieńkowska said. “Europe’s answer is the development of the next-generation of cost-effective reliable and competitive European launchers — Ariane 6 and Vega-C. We will aggregate our institutional launches to support those two launchers.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.