An uncrewed spacecraft landed in China’s Inner Mongolia region Monday after nearly 13 days in orbit carrying an array of microgravity research experiments, including a groundbreaking investigation that showed mammal embryos can develop in space, Chinese state media reported.

The Shijian 10 re-entry module landed in the Siziwang Banner of Inner Mongolia at about 0830 GMT (4:30 a.m. EDT; 4:30 p.m. Beijing time) Monday, according to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency.

Protected by a heat shield, the landing section re-entered Earth’s atmosphere after separating from the Shijian 10 spacecraft’s orbital module, which remained in space to conduct further experiments.

The mission, also called SJ-10, carried 19 experiments investigating fluid physics, combustion in space, materials science, biotechnology, and the effects of microgravity and radiation on plants and animals, according to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which manages the program.

Some initial results from the experiments are already publicized.

Researchers stowed more than 6,000 mouse embryos into a chamber the size of a microwave oven aboard Shijian 10, according to Xinhua.

The official media outlet reported pictures sent back by a high-resolution camera inside the chamber showed that the embryos developed similar to the way they do on Earth.

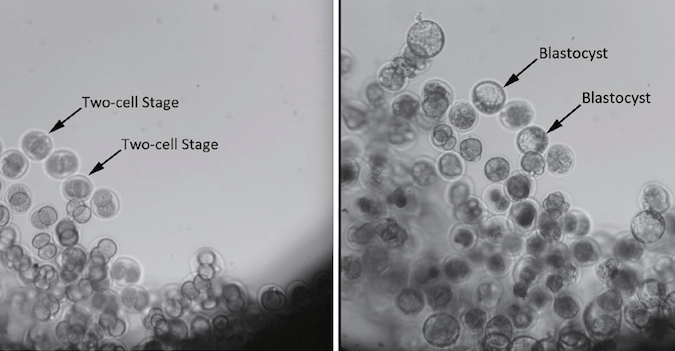

About 600 embryos put under the camera “developed from the two-cell stage, an early-on embryonic cleavage stage, to blastocyst, the stage where noticeable cell differentiation occurs, around 72 hours after SJ-10’s launch,” Xinhua reported. “The timing was largely in line with embryonic development on Earth, according to CAS (Chinese Academy of Sciences).”

The camera took pictures of the embryos every four hours, watching their development in a solution of nutrients to fuel their growth.

Chinese researchers claimed the experiment is the first to show that mammal embryos can “develop completely” in space.

The result is critical if humans ever colonize the solar system.

“The human race may still have a long way to go before we can colonize the space,” said Duan Enkui, professor at the Institute of Zoology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a report published by the state-run China Daily newspaper. “But before that, we have to figure out whether it is possible for us to survive and reproduce in the outer space environment like we do on Earth.

“Now, we finally proved that the most crucial step in our reproduction – the early embryo development – is possible in the outer space,” Enkui told China Daily.

Scientists will transport the embryos recovered from the Shijian 10 capsule to a Beijing laboratory for further analyses to determine how fast they developed and changes in gene and protein expression, according to China Daily.

The 11 experiments inside the Shijian 10 landing craft were in good condition after Monday’s landing, Xinhua reported.

The Shijian 10 mission is China’s 24th successful recoverable satellite mission since the 1970s. Another probe was lost in a launch failure.

Other investigations flown on Shijian 10 included studies of how solid materials and wiring insulation ignite and burn in microgravity, how space radiation damages DNA, and the development of silkworm embryos in microgravity, according to a mission overview released by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

One of the experiments was jointly developed by scientists in China and Europe to look at how oil is stored in natural reservoirs in Earth’s crust.

Six samples of crude oil, each with a volume of just one milliliter, are stowed inside sturdy titanium cylinders on the Shijian 10 satellite. They are compressed to 500 times the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere at sea level, mimicking conditions where crude oil pools deep underground.

The goal of the experiment is to study how temperature affects how crude oil molecules move.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.