Russian rocket technicians fueled a decommissioned ballistic missile with propellants Monday, a day ahead of the launch of a European satellite primed to observe the planet’s oceans.

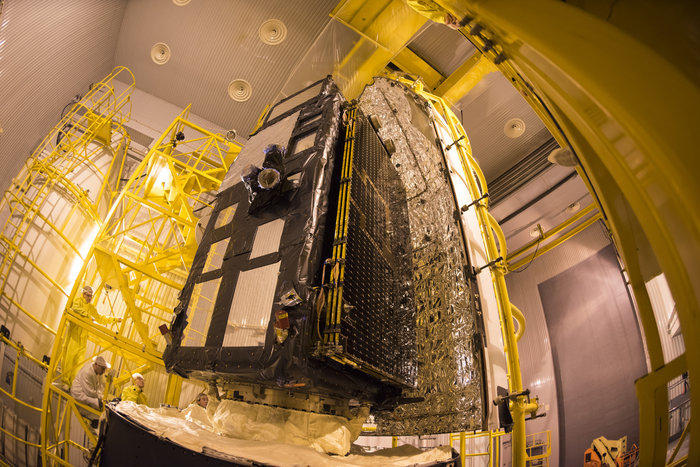

Europe’s Sentinel 3A Earth observing spacecraft is fastened atop a Rockot launch vehicle at the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, a military spaceport in Russia’s Arkhangelsk region about 500 miles (800 kilometers) north of Moscow.

Sentinel 3A is poised to become the third satellite to join Europe’s Copernicus program, which will become the world’s largest environmental satellite system when fully deployed in the early 2020s.

Military ground crews attached the spacecraft and its Breeze KM upper stage to the top of the Rockot launcher Friday, then fueled the rocket with a toxic mixture of hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants Monday.

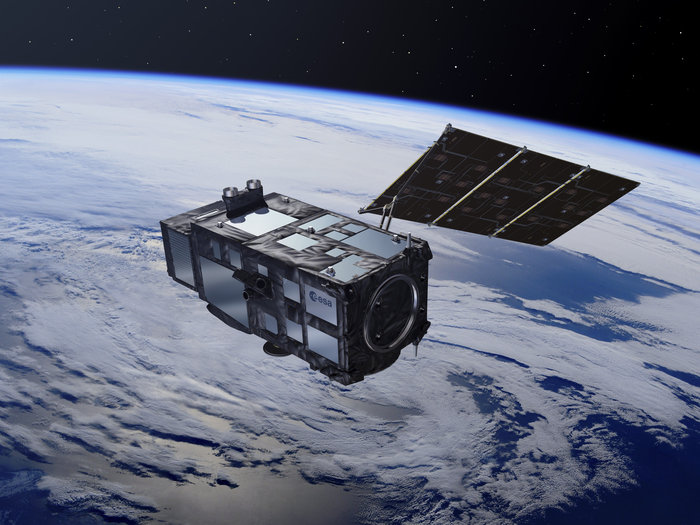

The new spacecraft carries two instruments to measure the temperature and color of the world’s oceans and land surfaces, and a radar altimeter to measure rising sea levels, the amount of water in rivers and lakes, and changes in polar ice sheets.

It will contribute to the Copernicus program’s unparalleled surveys of Earth, sending data to policymakers, maritime operators, resource planners and scientists in Europe and abroad to help take the pulse of the planet with record regularity.

An identical satellite named Sentinel 3B will launch at the end of 2017. Working in tandem, the pair of spacecraft will map the world every two days.

“It’s at our service, at your service, and at my service,” said Craig Donlon, Sentinel 3’s mission scientist at the European Space Agency. “It’s delivering measurements within three hours from sensing 24/7, 365 days per year for the next 15 or 20 years, and that’s really a quantum change in what we can do both in science (and) to give us that bigger picture.”

Flying more than 500 miles (800 kilometers) above Earth, Sentinel 3A will peer down at Earth, gather data and broadcast its measurements to users within hours.

“Over the ocean, we will have mean sea level data, we will have information about marine biology, and we will have information about sea surface temperature,” said Susanne Mecklenburg, ESA’s Sentinel 3 mission manager. “Over land, we will cover things like vegetation, agricultural applications, and water resource management by monitoring the heights of rivers and lakes, for example.”

The European Commission, the EU’s executive body, plans to spend up to $10 billion on the Copernicus program through 2020, making it Europe’s single most expensive space project. ESA oversees the development of most of the Copernicus program’s satellites and launches on behalf of the European Commission.

Sentinel 3A’s launch comes after the deployments of Sentinel 1A and Sentinel 2A — designed for disaster response and land surveys — in April 2014 and June 2015.

“Sentinel 3A’s multi-instrument payload, covering both optical and microwave measurements and serving a wide range of practical applications, is going to be the workhorse for Copernicus,” said Bruno Berruti, ESA’s project manager.

Liftoff of Sentinel 3A is set for 1757 GMT (12:57 p.m. EST) from Complex 133 at Plesetsk, when the Rockot booster will ignite its first stage engines and fire out of a launch tube, climbing away from the snow-covered cosmodrome on a northerly path toward a polar orbit.

The 95-foot-tall (29-meter) rocket, derived from an SS-19 missile built to deliver nuclear warheads to targets, will accelerate past the speed of sound in less than a minute, then shed its first stage at T+plus 2 minutes, 16 seconds.

The Rockot’s second stage will take over to propel Sentinel 3A into space, and the launcher’s 8.5-foot-diameter (2.6-meter) payload shroud will fall away at T+plus 3 minutes, 3 seconds, according to a mission timeline provided by Khrunichev State Research and Production Space Center, the Rockot’s Russian contractor.

The two-stage Rockot booster will push the Sentinel 3A satellite to a speed of more than 12,500 mph, or about 5.6 kilometers per second, before releasing a Breeze KM upper stage at T+plus 5 minutes, 19 seconds.

Moments later, the Breeze KM engine will start up for a nine-minute burn to place Sentinel 3A into a preliminary egg-shaped parking orbit. After flying over Greenland, Canada, the Western United States and the Pacific Ocean, the rocket will pass over Antarctica before firing the Breeze KM’s engine again.

The second burn, set to begin at 1912 GMT (2:12 p.m. EST) and last 32 seconds, will circularize the satellite’s orbit at an altitude of about 500 miles, or 800 kilometers.

The Breeze KM upper stage is programmed to release the Sentinel 3A satellite at T+plus 1 hour, 19 minutes and 50 seconds, according to Khrunichev.

Separation of the satellite will occur as it passes over a communications station in Malindi, Kenya. A follow-up pass over Sweden a few minutes later will give ground controllers at ESA’s satellite control in Darmstadt, Germany, their first chance to diagnose the health of the newly-launched spacecraft.

Sentinel 3A will then stabilize itself before unfurling the satellite’s power-generating solar array wing, Berruti said.

The spacecraft’s on-board computer will detect its spin rate after separation from the Rockot’s Breeze KM upper stage, and deployment of the solar panel will be timed depending on how long it takes for Sentinel 3A to autonomously gain control of itself.

“If the conditions of separation are a little bit noisy, so if we have a little bit more spin, then the satellite first has to reduce the torque within a certain predefined rate, and then solar array deployment can start,” Berruti said in an interview with Spaceflight Now on Friday.

The control software’s flexibility gives the satellite more time to overcome any tumble after separation from the launcher, but it could mean a long wait for ground controllers to verify Sentinel 3A is generating power to recharge its battery, which only has about five to six hours of charge at the time of launch.

“Depending on the characteristics of separation, this could last a minimum of 20 minutes or a maximum of three-and-a-half hours,” Berruti said. “We have a relatively big period of time in which the solar array deployment could occur.”

Designed to operate at least seven years, Sentinel 3A is about the size of minivan, and it weighs 2,526 pounds (1,146 kilograms) with a full tank of fuel at launch, according to Berruti.

It was manufactured by Thales Alenia Space of France, which received a contract in early February to build the third and fourth satellites in the Sentinel 3 series — Sentinel 3C and 3D — for launches as soon as 2021.

Within three days, Sentinel 3A should be fully activated and ready for tests and commissioning. If all goes according to plan, Sentinel 3A should be operational by mid-July, Berruti said.

Engineers will incorporate lessons learned from Sentinel 3A into the final preparations for the launch of the follow-on Sentinel 3B spacecraft at the end of 2017. Sentinel 3B will blast off aboard a European Vega rocket from French Guiana.

“The idea is that we will launch the first model now, and it should become operational in July,” Berruti told Spaceflight Now in a phone interview from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome. “During this phase, we will also have the opportunity to confirm that the ground calibration of the optical instruments is correct, or we can identify improvements we could do. At that point, we will complete the optical instruments and integrate them on the (Sentinel 3B) satellite.”

The Sentinel 3A and 3B satellites have a combined value of approximately 515 million euros, or about $575 million, Berruti said.

About two-thirds of that cost can be attributed to Sentinel 3A because it is the first satellite in the series, he said.

After accounting for the 30 million euro ($34 million) value of ESA’s contract with Eurockot, a German-Russian venture managing commercial Rockot launch services, the cost of Sentinel 3A’s mission could be estimated at more than $400 million.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.