STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

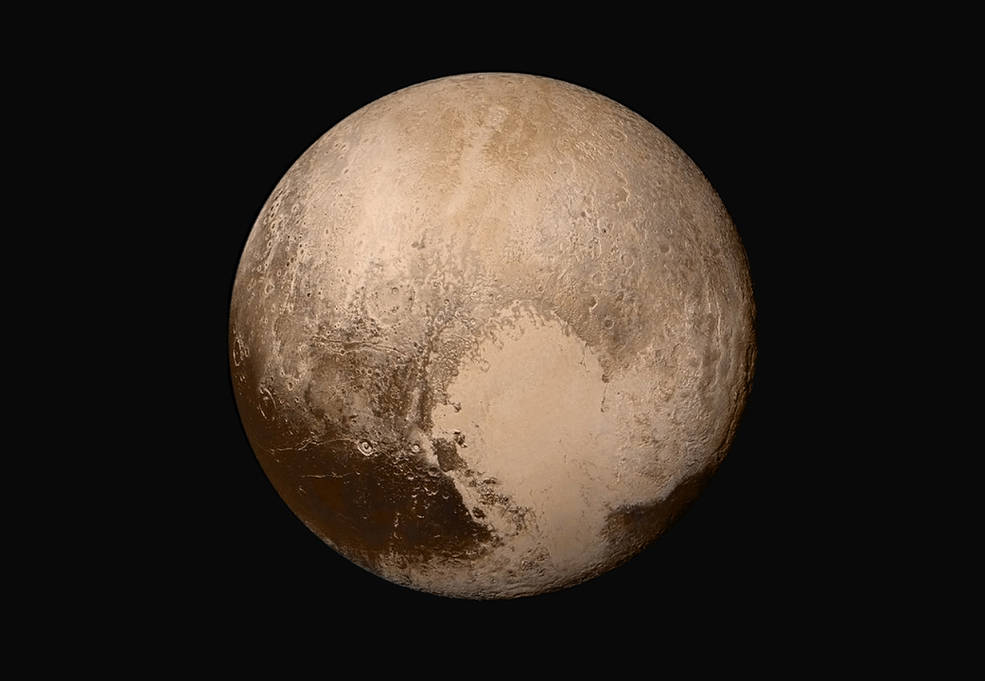

Nearly six months after NASA’s New Horizons probe zoomed past Pluto, just one quarter of the data stored on board has made its way back to waiting scientists, revealing a surprisingly varied terrain that includes craters, glacial flows in vast, icy plains and steep mountains of frozen water floating in a “sea” of slush-like nitrogen ice.

While New Horizons has answered many of the most outstanding questions about the solar system’s famously demoted outermost “planet,” the project’s principal investigator said Tuesday the science team expects a steady stream of new discoveries in the months ahead as the spacecraft slowly but surely sends back its treasure trove of stored data.

“Three quarters of (the recorded data) is still up on the spacecraft, and no one has seen it,” Alan Stern told astronomers at the American Astronomical Society’s winter meeting near Orlando, Fla. “So we expect to be having presents continue to rain down throughout most of this year, probably into October or November.”

Launched in January 2006, New Horizons raced past Pluto and its moons on July 14 and is now sailing ever deeper into the Kuiper Belt where uncounted remnants left over from the birth of the solar system orbit in frozen anonymity.

Now twice as far beyond Pluto as Earth is from the sun, New Horizons has beamed back stunning high-resolution views of the dwarf planet’s hazy, backlit atmosphere and surface, revealing a vast heart-shaped ice plain informally known as Sputnik Planum surrounded by jumbled ice mountains towering as high as the Rockies on Earth.

“Sputnik Planum is a vast ice field … and is ringed by mountain ranges all the way around,” Stern said. “It sits about three to four kilometers (2.5 miles) below those mountain ranges and we believe it’s actually a large impact basin.”

The presumed impact that created that basin would have released an enormous amount of energy, probably increasing the world’s tilt.

“It’s so large and its volume is so great that the negative mass anomaly caused by that impact has very likely caused the (tilt) of the planet to shift and to move this object to its current location near the equator of Pluto,” Stern said.

Before New Horizons reached Pluto, scientists did not known whether they would find steep topography like mountain ranges “because nitrogen ice, which is the dominant constituent of Pluto’s surface seen spectroscopically from Earth, is a very weak material even at 40 Kelvin (-387 F),” Stern said.

“It has the consistency, or the viscosity, of toothpaste, and if you try and build a mountain out of it, it’ll slump and relax, even in Pluto’s low gravity, over very short time scales.”

Steep topography — mountains — would be evidence that nitrogen ice “was thin, just a veneer on the surface, and that the constructional material had to be something much stronger,” Stern said. “Most likely water ice, because water ice is the most common constructional material on everything in the outer solar system that’s not a giant planet.”

Data from New Horizons confirmed the mountains are indeed made of ice, huge blocks of ultra-hard, deeply frozen water ice many miles across. The peaks, many of which feature methane icecaps, have a chaotic appearance and do not resemble coherent mountain ranges, Stern said, which “may be the result of that large impact that is believed to have created Sputnik Planum.”

“But the interesting thing is that water ice actually floats in nitrogen ice, it’s less dense, so it will tend to rise,” he said. “And these water ice blocks appear to have been removed from a subsurface layer and … borne up to the surface where they are now floating in that large nitrogen ice reservoir called Sputnik Planum.”

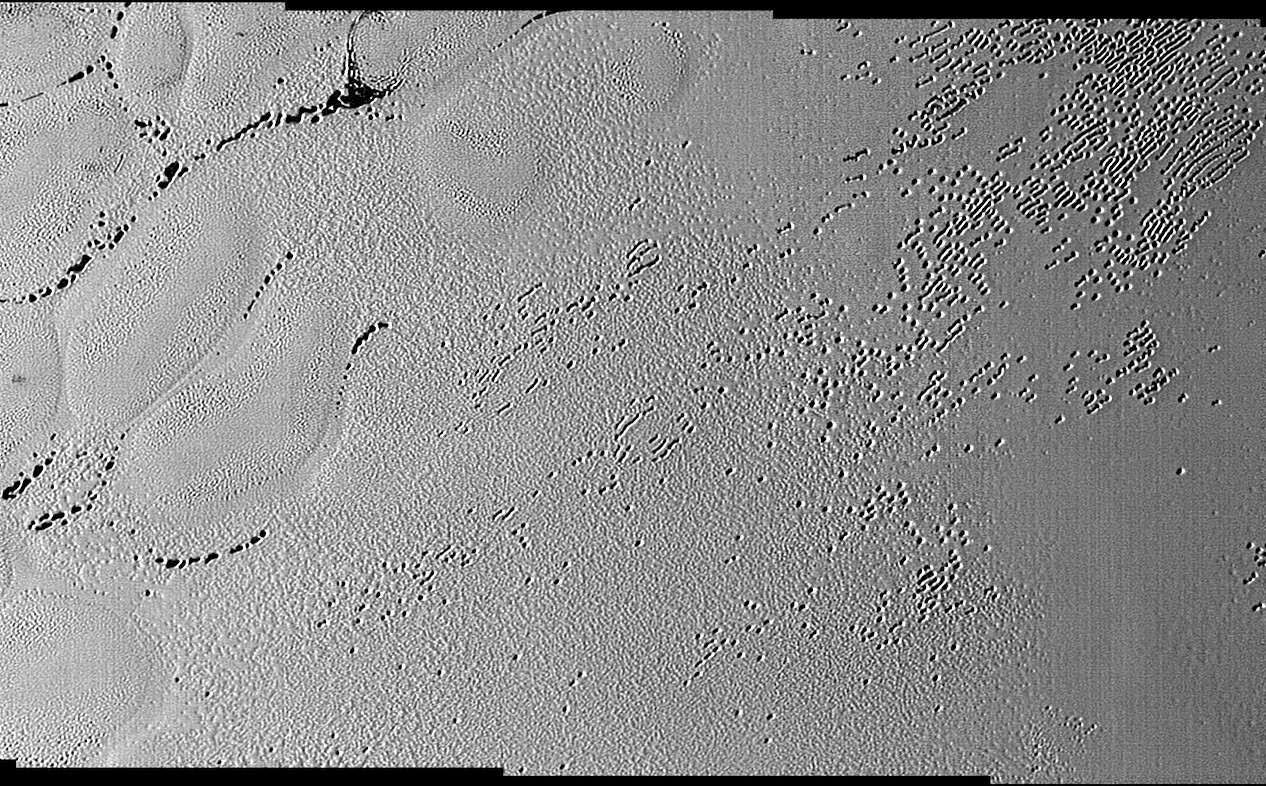

The plain itself features strange cell-like structures, or “ovoids,” that are believed to be the result of thermal convection in the ice. And that convection presumably helps resurface Sputnik Planum.

“We have looked and looked and looked and even in high-resolution imaging, we can’t find a single crater on the surface of Sputnik Planum in almost a million square kilometers,” Stern said. “And that tells us that (the surface) is very young, and that it’s being continually renewed.”

That was a major surprise, he added.

“We didn’t predict, as planetary scientists, that a small planet like Pluto with a large surface area-to-mass ratio could still be active and would not have completely cooled off after four billion years. And yet it has.”

Likewise, glacial flows were not expected because none are seen on icy satellites elsewhere in the solar system. But New Horizons has spotted obvious flow patterns where nitrogen ice apparently creeps around obstacles and other areas where ice has “poured down out of the mountains and pooled into Sputnik Planum,” Stern said. “That may be the mechanism by which it filled up with nitrogen in the beginning. We’ll see.”

Also surprising: countless pits across the southern parts of Sputnik Planum that can measure miles across and hundreds of yards deep.

“They look like bacteria. They are not!” Stern joked. “In any case, these sublimation pits are essentially ubiquitous across the southern portions of Sputnik Planum. … Some of the sublimation pits have merged, and it appears that the material beneath the ice is very dark.”

One working hypothesis, he said, is that everywhere on Pluto the “actual planet” is very dark and all of the regions that are bright are due to ices deposited on the surface by atmospheric transport.

“It appears this is confirming that, because we can see through the volatiles down to what appears to be the dark heart of Pluto.”

New Horizons is on course to fly by another Kuiper Belt body on Jan. 1, 2019.