EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated at 2 p.m. EST (1900 GMT) after end of spacewalk.

STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

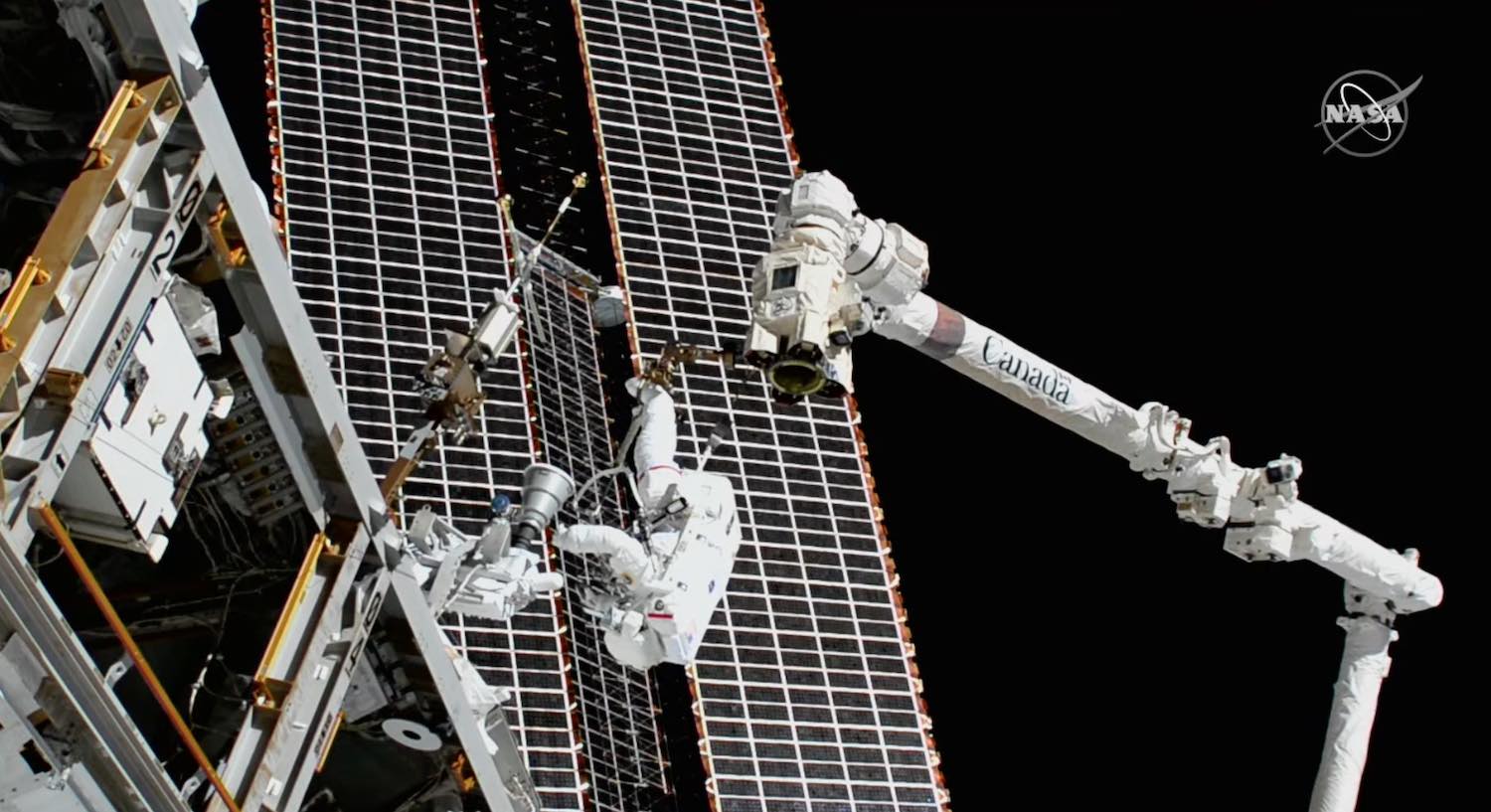

Running two days late because of concerns about possibly threatening space debris, a veteran astronaut and a rookie crewmate floated outside the International Space Station Thursday and replaced a faulty antenna in a problem-free 6.5-hour spacewalk.

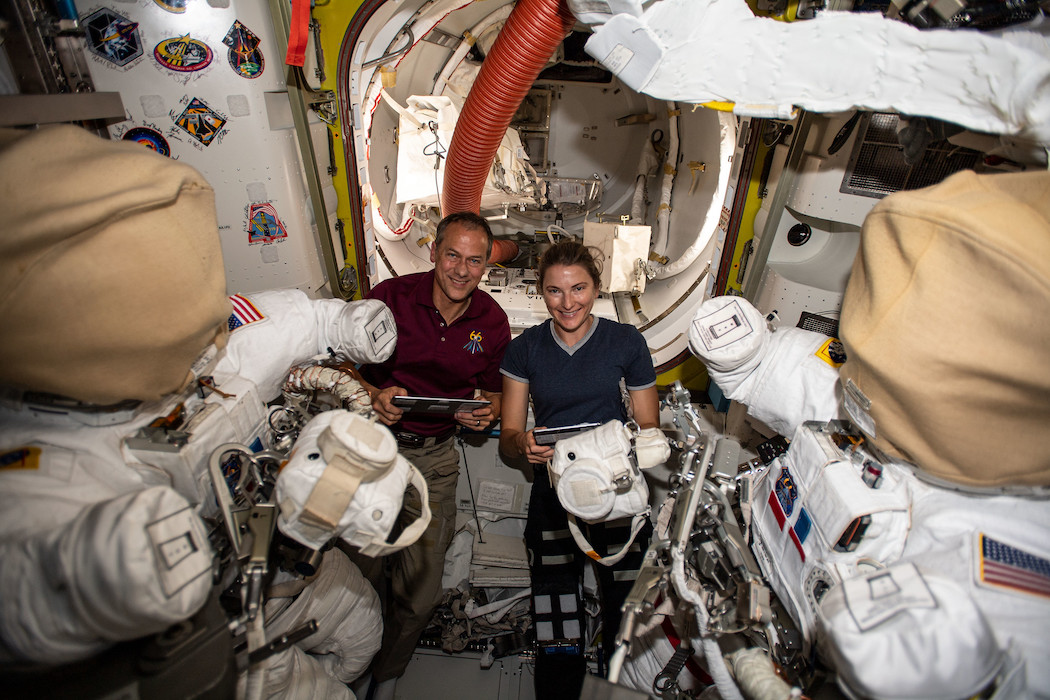

Floating in the lab’s Quest airlock, astronauts Thomas Marshburn and Kayla Barron switched their spacesuits to battery power at 6:15 a.m. EST to officially kick off the year’s 13th spacewalk, or EVA, the 245th since the lab’s assembly began in 1998.

Marshburn, a three-flight veteran and at 61, the oldest astronaut to walk in space, logged 24 hours and 29 minutes of spacewalk time during four previous excursions while Barron, a Navy submarine officer, was making her first.

The primary goal of the EVA was to replace a failed S-band antenna on the left side of the station’s power truss with a spare unit stored on an external logistics platform.

The station has multiple antennas in a highly redundant communications system that feature high-data-rate Ku-band antennas and slower S-band units. Managers want to replace the failed S-band module before the lab’s orbit carries it into extended periods of sunlight and higher temperatures.

Marshburn spent most of the spacewalk riding on the end of the space station’s robot arm, working with Barron to remove the failed unit, install its replacement and then stow the old antenna on the logistics platform.

“Good news, we have a working SASA antenna,” astronaut Drew Morgan radioed from mission control after the new unit was checked out. “Great job.”

Before wrapping up the excursion, Barron carried out two lower-priority “get-ahead” tasks,” loosening bolts holding two electrical components in place at the base of one of the lab’s solar arrays to make future replacements easier. The astronauts returned to the airlock and began repressurization at 12:47 p.m., bringing the six-hour 32-minute spacewalk to an end.

“Kayla and Tom, I asked you to crush it but man, you all triple crushed it,” astronaut Mark Vande Hei called from inside the station, congratulating the returning spacewalkers.

The astronauts originally planned to carry out the spacewalk Tuesday, but NASA ordered a delay to fully evaluate possibly threatening space debris to determine what sort of risk it might pose to the astronauts. Later that same day, mission managers concluded it would be safe to proceed with the excursion Thursday.

The agency did not provide any details about the nature of the debris or the level of risk it represented. The incident occurred just two weeks after a Russian anti-satellite weapon test that destroyed a retired satellite and generated a cloud of debris.

Sources said the debris in question this week may not have been generated in the ASAT test, but that could not be immediately confirmed.

Thousands of objects the size of a softball and larger are routinely tracked by Space Force radars on the ground. For trackable objects on a collision course with the station, the lab can fire thrusters to move out of the way. But objects too small to track can hit without warning.

The Russian ASAT test generated about 1,700 pieces of trackable debris and an unknown number of smaller fragments. The debris has now spread out and NASA officials said Monday the risk to Marshburn and Barron was only about 7 percent higher than the normal 1-in-2,700 odds of a spacesuit penetration.

Presumably, the threat level is in that same ball park after the risk assessment Tuesday, but no such details were provided.

The danger posed by space debris was a topic of discussion Wednesday during the first meeting of the National Space Council under the Biden administration. The White House council oversees U.S. military, civil and commercial space operations.

Vice President Kamala Harris, chair of the panel, condemned the Russian ASAT test and said the United States would lead an effort to establish international “rules and norms” to enhance safety for astronauts and spacecraft alike.

“Without clear norms for the responsible use of space, we stand the real risk of threats to our national and global security,” she said. “Just last month, we saw what can happen. Russia launched an anti-satellite missile to destroy one of its satellites.”

That “irresponsible act,” she said, “endangered the satellites of other nations, as well as astronauts in the International Space Station. As activity in space grows, we must reaffirm the rights of all nations, and we must demand responsibility from all spacefaring nations.”

Russia claims the ASAT test was designed to minimize threatening debris and tweeted Wednesday, shifting the focus, that a fragment from an old American Pegasus rocket was predicted to make a close pass by the station Friday.

“A fragment of … the American Pegasus rocket will approach the ISS on December 3,” the Russian space agency Roscosmos tweeted. “Roscosmos specialists continue to monitor the situation.”

But U.S. officials have roundly criticized the Russian test. Kathleen Hicks, deputy Secretary of Defense, told Harris the Russian ASAT test “really demonstrates the potential deadly effects” if rules and norms are not followed.

“We’ve seen significant amounts of hazardous debris created that can threaten and could still threaten the lives of those space travelers who are in low Earth orbit,” she said of the ASAT test. “And that risk will continue for years.

“Such a display of deliberate disregard for safety, stability, security and sustainability in space is one that is to be condemned, and underscores the urgency of acting in defense of developing shared norms and having long-term sustainability of outer space.”

From the Pentagon’s perspective, she added, “we would like to see all nations agree to refrain from anti-satellite weapons testing that creates debris, which pollutes the space environment, risks damaging (spacecraft) and threatens the lives of current and future space explorers.”

The International Space Station and the SpaceX Crew Dragon capsules that ferry astronauts to and from the outpost are equipped with shielding designed to prevent penetrations by smaller, untracked debris fragments and micrometeoroids.

NASA’s shuttle-era spacesuits are more vulnerable, but they feature a 30-minute emergency oxygen supply to enable an astronaut to make it back to the safety of an airlock in an emergency. No such debris-related emergency has ever been declared.