Galileo's flyby reveals Callisto's bizarre landscape

NASA/JPL NEWS RELEASE

Posted: August 23, 2001

A spiky landscape of bright ice and dark dust shows signs of slow but active erosion on the surface of Jupiter's moon Callisto in new images from NASA's Galileo spacecraft.

The pictures taken by Galileo's camera on May 25 from a distance of less than 138 kilometers, or about 86 miles, above Callisto's surface give the highest resolution view ever seen of any of Jupiter's moons.

Bright scars on a darker surface testify to a long history of impacts on Jupiter's moon Callisto in this image of Callisto from Galileo. The picture, taken in May 2001, is the only complete global color image of Callisto obtained by Galileo. Callisto's surface is uniformly cratered but is not uniform in color or brightness. Scientists believe the brighter areas are mainly ice and the darker areas are highly eroded, ice-poor material. Credit: NASA/JPL/DLR (German Aerospace Center)

|

"We haven't seen terrain like this before. It looks like erosion is still going on, which is pretty surprising," said James Klemaszewski of Academic Research Lab, Phoenix, Ariz. Klemaszewski is processing and analyzing the Galileo Callisto imagery with Dr. David A. Williams and Dr. Ronald Greeley of Arizona State University, Tempe. The images were released by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., which manages the Galileo mission.

Callisto, about the same size as the planet Mercury, is the most distant of Jupiter's four

large moons. Callisto's surface of ice and rock is the most heavily cratered of any moon in the

solar system, signifying that it is geologically "dead." There is no clear evidence that Callisto has

experienced the volcanic activity or tectonic shifting that have erased some or all of the impact

craters on Jupiter's other three large moons.

The jagged hills in the new images may be icy material thrown outward from a large impact billions of years ago, or the highly eroded remains of a large impact structure, Williams

said. Each bright peak is surrounded by darker dust that appears to be slumping off the peak.

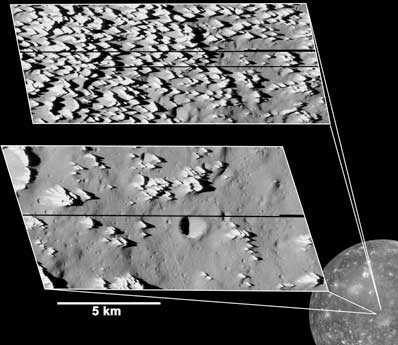

The highest-resolution views ever obtained of any of Jupiter's moons, taken by Galileo in May 2001, reveal numerous bright, sharp knobs covering a portion of Jupiter's moon Callisto. The knobby terrain seen throughout the top inset is unlike any seen before on Jupiter's moons. The spires are very icy but also contain some darker dust. As the ice erodes, the dark material apparently slides down and collects in low-lying areas. Over time, as the surface continues to erode, the icy knobs will likely disappear, producing a scene similar to the bottom inset. The number of impact craters in the bottom image indicates that erosion has essentially ceased in the dark plains shown in that image, allowing impact craters to persist and accumulate. The knobs are about 80 to 100 meters (260 to 330 feet) tall, and they may consist of material thrown outward from a major impact billions of years ago. The areas captured in the images lie south of Callisto's large Asgard impact basin. Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University

|

"They are continuing to erode and will eventually disappear," Klemaszewski said. One

theory for an erosion process is that, as some of the ice sublimes away into vapor, it leaves

behind dust that was bound in the ice. The accumulating dark material may also absorb enough

heat from the Sun to warm the ice adjacent to it and keep the process going. The new images

show portions of the surface where the sharp knobs have apparently eroded away, leaving a plain

blanketed with dark material.

The close-up images show craters as small as about 3 meters (10 feet) across, though not

as many as some predictions anticipated. One scientific goal from the high-resolution images is

to see how many small craters are crowded onto the surface. Crater counts are one way to

estimate the age of a moon's surface, and since Callisto has been so undisturbed by other

geological processes, its cratering density is useful in calibrating the estimates for Jupiter's other

moons.

JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages Galileo for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C.

|

|

|

|

|