Ocean believed hidden on solar system's largest moon

NASA/JPL NEWS RELEASE

Posted: December 16, 2000

Add Jupiter's moon Ganymede, which is bigger than two of

the solar system's nine planets, to the growing list of worlds

with evidence of liquid water under the surface.

A thick layer of melted, salty water somewhere beneath

Ganymede's icy crust would be the best way to explain some of

the magnetic readings taken by NASA's Galileo spacecraft during

close approaches to Ganymede in May 2000 and earlier, according

to one new report.

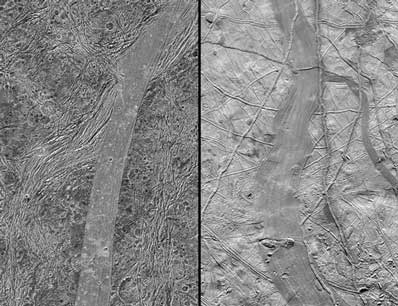

This image, taken by Galileo, shows a same-scale comparison between Arbela Sulcus on Jupiter's moon Ganymede (left) and an unnamed band on Europa (right). Arbela Sulcus is one of the smoothest lanes of bright terrain identified on Ganymede, and shows very subtle striations along its length. Arbela contrasts markedly from the surrounding heavily cratered dark terrain. On Europa, dark bands have formed by tectonic crustal spreading and renewal. Bands have sliced through and completely separated pre-existing features in the surrounding bright ridged plains. The scarcity of craters on Europa illustrates the relative youth of its surface compared to Ganymede's. Unusual for Ganymede, it is possible that Arbela Sulcus has formed by complete separation of Ganymede's icy crust, like bands on Europa. Photo: NASA/JPL/DLR/Brown University. SEE THE FULL SCREEN VERSION

|

In addition, the types of minerals on parts of Ganymede's

surface suggest that, in the past, salty water may have emerged

from below or melted at the surface, according to a study of

infrared reflectance measured by Galileo.

Third, new Galileo images of Ganymede hint how the water or

slushy ice may have surfaced through the fractured crust,

reminiscent of linear features on Europa, a neighboring moon

believed likely to have a deep ocean beneath its ice.

Several of the new images, prepared by researchers at Brown

University, Providence, R.I., and the German Aerospace Center

(DLR), Berlin, Germany, are available from NASA's Jet Propulsion

Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

They include the most detailed photos ever taken of

Ganymede and an animated virtual flyover of an area where a

smooth, bright swath resembling parts of Europa cuts across

older, more heavily cratered terrain.

The new information about Ganymede is being presented at

the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, beginning

Dec. 15 in San Francisco. Ganymede is the biggest moon

in the solar system and bigger than the planets Mercury and

Pluto. It was named for a boy in Greek mythology who was so

beautiful that Jupiter, king of the gods, had him brought to

Olympus by an eagle.

This view of Arbela Sulcus, a 24-kilometer-wide (15-mile-wide) region of furrows and ridges on Ganymede, shows its relationship to the dark terrain surrounding it. NASA's Galileo took these pictures during its May 20 flyby. Arbela Sulcus lies overall slightly lower than the dark terrain of Nicholson Regio, a 3,700 kilometers (3,300 mile) area in the southern hemisphere. However, along the eastern margin (bottom), a portion of the dark terrain (probably an ancient degraded impact crater) lies even lower than Arbela Sulcus. Scientists did not find bright icy material on Arbela Sulcus, indicating that this ridgy area was not created by watery volcanic activity. Instead, they found fine striations covering the surface, along with a series of broader highs and lows that resemble piano keys. This suggests that the movement of underlying tectonic plates deformed the surface. Combining images from two observations taken from different viewing perspectives provides stereo topographic information, giving valuable clues as to the geologic history of a region. Photo: NASA/JPL/DLR/Brown University SEE THE FULL SCREEN VERSION

|

The magnetic clues to a possible saltwater layer at

Ganymede are more complicated than earlier magnetic evidence of

hidden oceans on two other moons of Jupiter, Europa and

Callisto, said Dr. Margaret Kivelson, a planetary scientist at

the University of California, Los Angeles, and principal

investigator for Galileo's magnetometer instrument. That's

because Ganymede has a strong magnetic field of its own, instead

of just a secondary field induced by Jupiter's magnetism.

But the indications of an induced field at Ganymede are

"highly suggestive" of a salty ocean on Ganymede, too, Kivelson

said. "It would need to be something more electrically

conductive than solid ice," she said.

A melted layer several kilometers or miles thick, beginning

within 200 kilometers (120 miles) of Ganymede's surface would

fit the data if it were about as salty as Earth's oceans,

Kivelson said.

Ganymede is covered with lots of ice and frost, both in the

older, dark terrains and younger, bright terrains, said Dr.

Thomas McCord, a geophysicist at the University of Hawaii,

Honolulu, who has been using Galileo's infrared spectrometer

instrument to identify surface materials on Ganymede. Portions

of the moon appear to have types of salt minerals that would

have been left behind by exposure of salty water near or onto

the surface, he said.

"They are similar to the hydrated salt minerals we see on

Europa, possibly the result of brine making its way to the

surface by eruptions or through cracks," McCord said. The

infrared evidence does not indicate whether or not an ocean

persists at Ganymede today, he said.

Photos Galileo took as it passed within 809 kilometers (503

miles) of Ganymede on May 20 display details of a tumultuous

past, according to Drs. James Head III and Robert Pappalardo,

planetary scientists at Brown.

Arbela Sulcus on Jupiter's moon Ganymede (top) is compared with the gray band Thynia Linea on another Jovian moon, Europa (bottom), shown to the same scale. Both images are from NASA's Galileo spacecraft. Arbela Sulcus is one of the smoothest lanes of bright terrain identified on Ganymede, but subtle striations are apparent here along its length. This section of Arbela contrasts markedly from highly fractured terrain to its west and dark terrain to its east. On Europa, gray bands such as Thynia Linea have formed by tectonic crustal spreading and renewal. Such bands have sliced through and completely separated pre-existing features in the surrounding bright, ridged plains. The younger prominent double ridge Delphi Flexus cuts across Thynia Linea. The scarcity of craters on Europa attests to the relative youth of its surface compared to Ganymede's. Photo: NASA/JPL/DLR/Brown University.

|

"Bright broken swaths, disrupted dark plains and the

astounding Arbela Sulcus suggest Ganymede may be more similar to

Europa than previously believed," Pappalardo said. Arbela Sulcus

is a relatively smooth, bright band interrupting a more

cratered, older landscape. The new images show subtle striations

along its length. "It is possible that Arbela Sulcus has formed

by complete separation of Ganymede's icy crust, like bands on

Europa, but unusual for Ganymede," he said.

Natural radioactivity in Ganymede's rocky interior should

provide enough heating to maintain a stable layer of liquid

water between two layers of ice, about 150 to 200 kilometers (90

to 120 miles) below the surface, said Dr. Dave Stevenson,

planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology,

Pasadena. That's a difference from Europa, where interior

flexing from tidal effects of Jupiter's gravity provides much of

the internal heat, he said.

"I would have been surprised if Ganymede had not had an

ocean, but the issue of whether it's there is different than the

issue of whether you can expect to see it clearly in the data,"

Stevenson said.

Galileo has been orbiting Jupiter since Dec. 7, 1995. It

will fly past Ganymede again on Dec. 28, but will not come as

close as it did in May. The Galileo mission

is managed for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C.

by JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology.

|

|

|

|

|