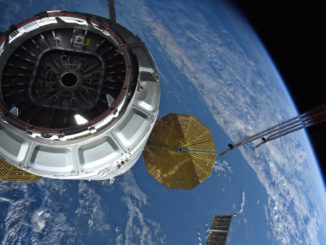

After a successful mission that pushed the limits of small satellite technology, ground controllers have lost contact with two briefcase-sized CubeSats beyond Mars, NASA said Tuesday.

The pioneering Mars Cube One, or MarCO, mission set records for the farthest distance CubeSats have ever operated, accompanying NASA’s InSight lander to Mars after a May 5 launch atop an Atlas 5 rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

The twin MarCO spacecraft relayed telemetry from InSight as it entered the Martian atmosphere Nov. 26 and successfully landed on the Red Planet, giving engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California updates on the lander’s progress. albeit with an eight-minute delay due to the time it took radio signals to travel the 91 million miles (146 million kilometers) from Mars to Earth.

InSight could have succeeded without MarCO, but engineers would have had to wait hours to receive confirmation of the landing.

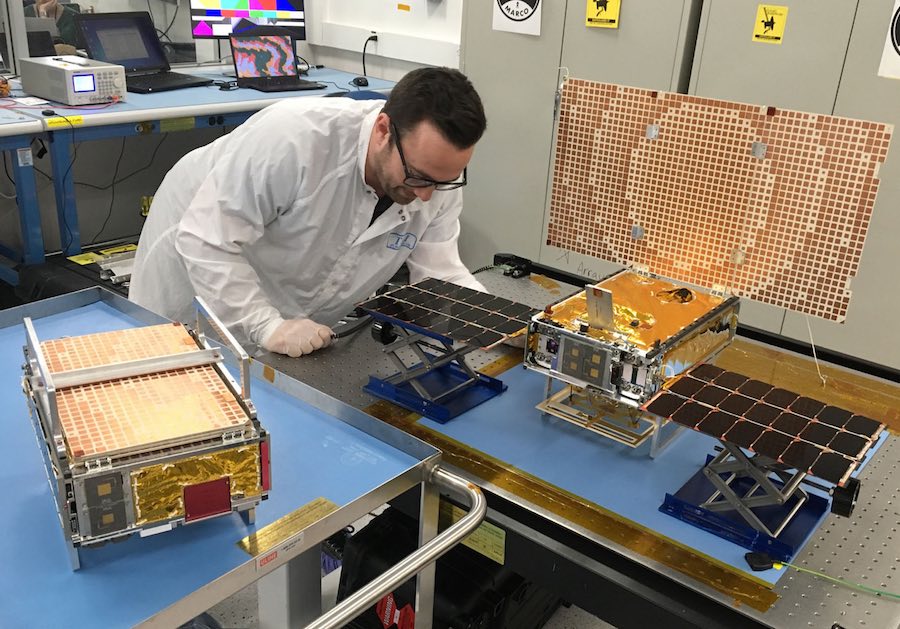

But MarCO was conceived primarily as an experimental mission to prove that CubeSats, with some modifications, could withstand the perils of deep space travel. CubeSats are much less expensive than larger satellites, and can cost less than $1 million to design and build for missions in Earth orbit.

The Mars Cube One mission cost $18.5 million, once engineers at JPL outfitted the satellites with a new type of radio, innovative antennas, a cold gas propulsion system, and other custom features needed for interplanetary spaceflight.

That’s still a fraction of the InSight mission’s $993 million cost.

NASA said Tuesday that it has been more than a month since ground controllers heard from either of the MarCO spacecraft, which measure 4.4 inches (36.6 centimeters) by 9.6 inches (24.3 centimeters) by 4.6 inches (11.8 centimeters) in size. Officials believe it is unlikely either MarCO CubeSat will be heard from again.

“This mission was always about pushing the limits of miniaturized technology and seeing just how far it could take us,” said Andy Klesh, the mission’s chief engineer at JPL. “We’ve put a stake in the ground. Future CubeSats might go even farther.”

Nicknamed EVE and WALL-E after the robot characters from the 2008 Pixar film, the MarCO spacecraft used compressed R236FA gas — commonly used in fire extinguishers — as a propellant for course corrections on the journey from Earth to Mars. The film character WALL-E uses a fire extinguisher to propel through space, giving the MarCO team the source for the spacecraft’s nicknames.

The compressed gas fed eight tiny thrusters on each satellite.

Each CubeSat weighed around 30 pounds (13.5 kilograms) at launch. They are considered “six-unit,” or 6U, CubeSats, which come in a scaleable form factor with 1U, 3U, 6U and 12U variants, depending on mission requirements. Each cubic “unit” measures around 4 inches (10 centimeters) on a side.

Ground teams last heard from WALL-E on Dec. 29, and from EVE on Jan. 4, NASA said in a statement. Officials said WALL-E is more than a million miles (1.6 million kilometers) past Mars, and EVE nearly 2 million miles (3.2 million kilometers) beyond the Red Planet, as the twin spacecraft orbit the sun.

“The mission team has several theories for why they haven’t been able to contact the pair,” NASA said in a statement. “WALL-E has a leaky thruster. Attitude-control issues could be causing them to wobble and lose the ability to send and receive commands.

“The brightness sensors that allow the CubeSats to stay pointed at the Sun and recharge their batteries could be another factor,” officials said in the statement. “The MarCOs are in orbit around the Sun and will only get farther away as February wears on. The farther they are, the more precisely they need to point their antennas to communicate with Earth.”

The MarCO CubeSats will move closer to the sun later this year, but engineers are not sure if their batteries and other components will last that long. Nevertheless, the ground team will attempt to contact the CubeSats again when prospects for communications improve.

Besides the propulsion system, another of the crucial technologies embedded inside each MarCO spacecraft is a miniaturized “Iris” radio, about the size of a softball, that crams advanced receive and transmission functions into a package that can fit into a CubeSat. The Iris radio interfaced with NASA’s Deep Space Network, a collection of antennas at three sites in California, Spain and Australia that connect with spacecraft traveling throughout the solar system.

Two compact antennas were also demonstrated on the MarCO mission.

One of the antennas on each CubeSat, operating in X-band, beamed signals back to Earth from distances as far away as Mars without needing much power, an essential capability for such small spacecraft. MarCO-A and MarCO-B also deployed a UHF radio antenna, which received telemetry from the InSight spacecraft as it descended through the Martian atmosphere.

The on-board radio converted the UHF signals from InSight to an X-band format for broadcast back to Earth.

WALL-E and EVE also carried wide-field cameras to document the deployment of the X-band high-gain antennas. The camera on EVE failed during the voyage to Mars, but WALL-E captured views of the Red Planet as the spacecraft sailed by it.

NASA plans to select smallsats and CubeSats to ride piggyback on launches carrying several of the agency’s future robotic science missions. Officials have set aside a mass and volume allotment for secondary payloads on the rockets launching the Lucy and Psyche spacecraft to explore asteroids, and the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, a mission to study the boundary between the sun’s heliosphere and interstellar space.

The Lucy, Psyche and IMAP missions are scheduled for launch in 2021, 2022 and 2024, respectively.

Thirteen CubeSats will also fly on the first launch of NASA’s Space Launch System no earlier than 2020, each with standalone missions to study the moon, travel to an asteroid, and conduct other types of research and demonstrations in deep space.

“There’s big potential in these small packages,” said John Baker, the MarCO program manager at JPL. “CubeSats — part of a larger group of spacecraft called SmallSats — are a new platform for space exploration that is affordable to more than just government agencies.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.