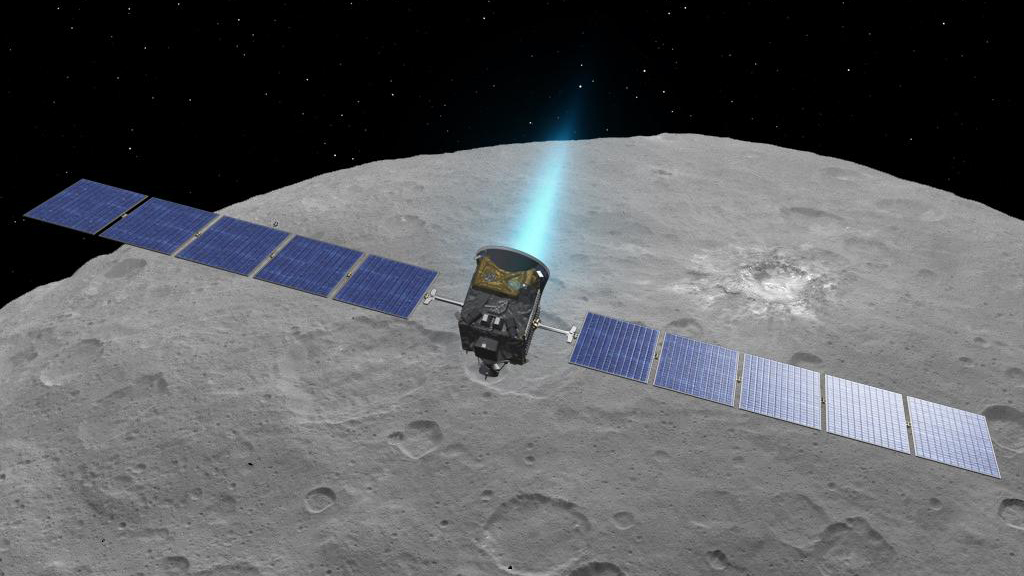

NASA’s robotic Dawn spacecraft is now getting its closest look at the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest resident of the asteroid belt, and mission managers say the probe has enough leftover propellant to keep flying into early 2017, several months beyond the prescribed end of its survey.

A year into its global study of Ceres, the Dawn spacecraft is now flying in its closest orbit around the airless world at an average altitude of 240 miles (385 kilometers) and getting its most detailed snapshots of the dwarf planet’s alien surface.

Ceres is the Dawn mission’s second destination after a visit to the giant asteroid Vesta. Powered by an efficient ion propulsion system, Dawn is the first spacecraft explore either of the diminutive worlds.

Scientists have identified many craters, fractures, mountains and ridges across Ceres’ landscape, which appears gray to the naked eye but is rich in subtle color variations revealed by Dawn’s instrument suite.

“Our first surprise was the topography,” said Chris Russell, the Dawn mission’s principal investigator from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Researchers expected Ceres — the largest object in the asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter — to be relatively smooth except for craters. Instead, Dawn found a rugged world with a rumpled, wavy-looking horizon as viewed from Dawn’s camera in orbit.

Many planetary scientists thought Ceres could have an icy outer shell, a characteristic that would tend to favor a flatter surface.

“We found more topographic relief than we had expected,” Russell said. “It’s about half that of Vesta, so it’s more subdued than Vesta but it’s still more than we would have expected if that crust had been an icy crust.”

Scientists studying data from a sensor measuring the energy emitted as cosmic radiation bombards the surface of Ceres have discovered the dwarf planet is “loaded” with hydrogen in the high latitudes of its northern hemisphere, said Tom Prettyman, principal investigator of Dawn’s gamma ray and neutron detector instrument from the Planetary Science Institute.

“If that’s the case, what form does it take? We know that the main reservoirs of hydrogen should be hydrogen-bound minerals and water ice,” he said in a presentation last month at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference near Houston.

Prettyman said the extrapolation of preliminary data from the gamma ray and neutron detector, which has only been operating a few months, indicates water ice is at or near the surface near Ceres’ north pole.

“Boy, is it a wonderful dataset,” he said.

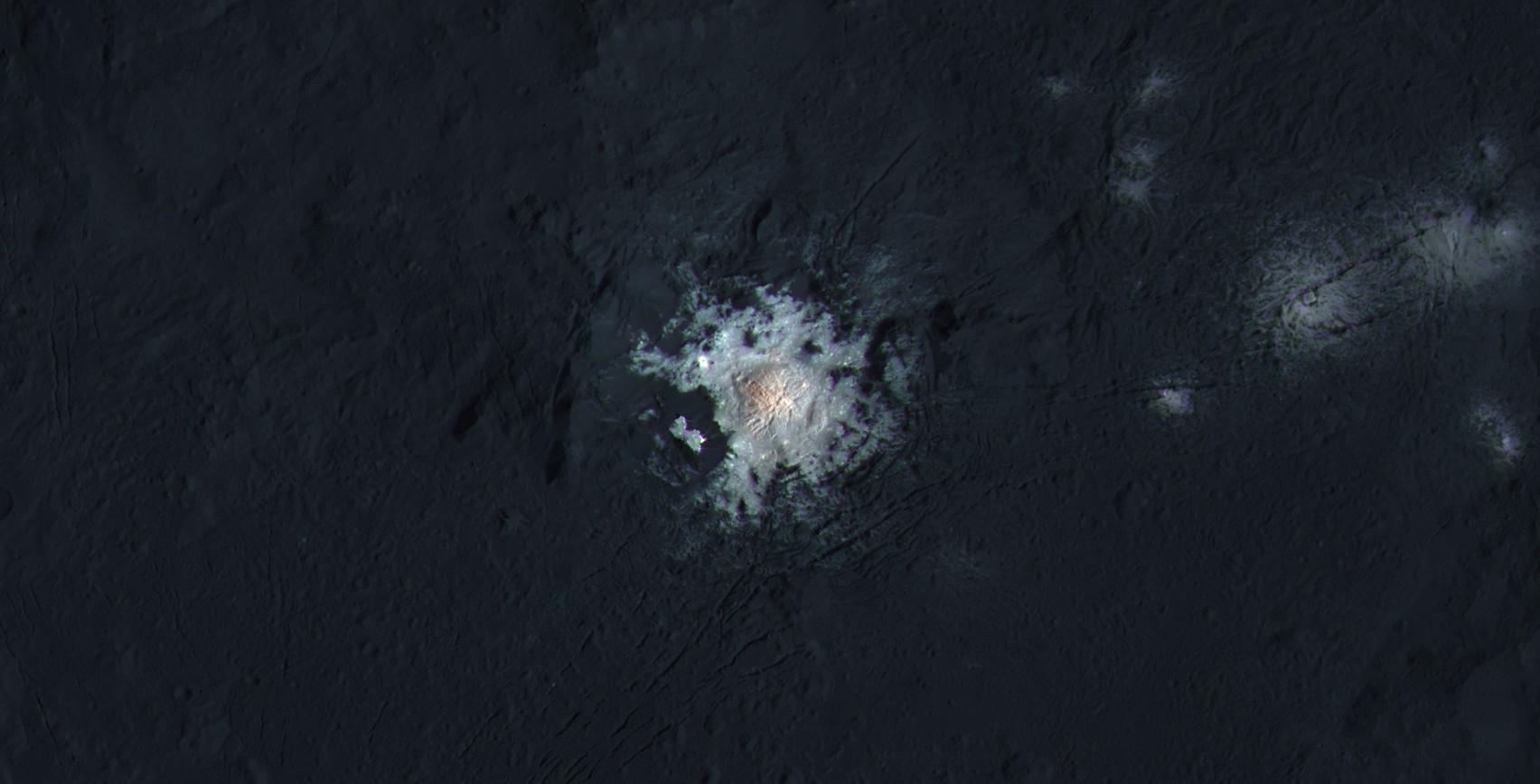

Textured imagery of Occator crater, a 57-mile (92-kilometer) basin first glimpsed as Dawn approached Ceres in early 2015, has revealed that mysterious bright spots there are irregular and likely made of salts left behind as water evaporated from the crater.

“When we approached Ceres, it got ever-larger and we saw that ever-intriguing bright spot on the surface, and the bright spot has continued to beguile us,” Russell told an audience at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference.

A close-up view shows a dome sitting inside a smooth-walled pit in the bright center of the crater, scientists said.

Scientists are still trying to determine the exact composition of the material, which Russell describes as a white powder made of chlorides, sulfides, carbonates, or a mixture of minerals.

“It is not a dropped flour bag,” Russell joked, referring to one popular description of the bright region’s appearance.

Carol Raymond, Dawn’s deputy principal investigator from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said Occator crater formed 70 to 80 million years ago when an asteroid or comet slammed into Ceres.

The leading theoretical explanation for the formation of the bright spots in Occator crater, and other impact sites on Ceres, is that the heat generated by the collision melted a mixture of rock, ice and salts lurking inside the frozen world’s crust.

“That’s a theory or a hypothesis that we’re investigating closely to try to explain whether we could get enough heat for a long enough period of time, what type of material would react to that amount of heat and become a cryo-magma — basically an ice- or salt-based magma that could come to the surface and produce the kinds of strange features that we’re seeing,” Raymond said.

But what caused the salts to persist at the surface when the water and magma dried up in the aftermath of the impact?

“One of the issues that is a bit of a paradox is that the crater that you saw is dated to be about 80 million years old,” Raymond said. “The bright material is extremely bright, and it’s hard to keep things bright on a planetary surface over time. Suffice it to say that we have a lot of work to do to work out the detailed composition of the different areas even within that crater, tie it back to the physics of the impact process mobilizing subsurface material, and then trying to explain the persistence of that bright material over geologic time.”

One impact cavity, called Oxo crater, contains water ice on the surface. So far, observations of the more famous Occator site have turned up no signature of exposed ice.

Some craters show dried flow patterns outside their rims, evidence that the impacts stirred up water and rock that streamed on Ceres’ surface for some period of time, according to Ralf Jaumann, the lead scientist for Dawn’s framing camera from DLR, the German Aerospace Center.

Raymond said Ceres appears to be a former ocean world and could have once been similar to Europa or Enceladus, the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

“One of the things that we anticipated about Ceres before getting there is that it’s a former ocean world,” Raymond said. “We’re so interested in going to Europa and Enceladus, and these other interesting objects in the outer solar system because we think they harbor subsurface oceans at present, and possible habitable environments, and possibly even locations where there’s extant life.

“Ceres appears to have been one of those objects in the past, when it was younger and hotter,” Raymond said. “What we’re looking at now is, we believe, the remnant of a frozen ocean. The salt is left over from the brines that were concentrated as the ocean froze out, so it’s all a fairly consistent story that Ceres is a former ocean (world) where the ocean froze, and now we’re interrogating the chemistry, essentially, of that ocean-rock interface through the subsurface layers that we’re detecting on Ceres.”

As Dawn’s data continues to roll in to research labs and science teams, engineers are focused on preserving the spacecraft’s finite supply of hydrazine rocket fuel in a bid to keep the mission running through early 2017.

The probe’s primary mission ends June 30, but mission managers expect Dawn to keep going for several months longer.

Engineers have battled issues with Dawn’s reaction wheels, rapidly-spinning devices which use momentum to keep the spacecraft pointed in the right direction. Two of the four wheels have failed, causing the craft to rely on its small rocket jets to stay pointed in some situations.

Dawn arrived in its low-altitude mapping orbit in December, and the mission’s ground team scripted the flight plan to complete all of the probe’s critical science observations in three months. Ceres’ uneven gravitational field disrupts the spacecraft’s orbit, requiring occasional course corrections that consume fuel, so engineers did not count on Dawn continuing beyond March.

Raymond said Dawn is now in position to keep going through at least June 30.

“We are operating incredibly elegantly with two reaction wheels and hydrazine jets,” she told reporters last month. “We can finish our primary mission. “If we lost a wheel tomorrow, then we would continue on using the reaction control system (jets) and be able to complete our primary mission without any problem.”

Manufactured by Orbital ATK, Dawn is currently orbiting Ceres with its sensors pointed 5 degrees away from straight down toward the dwarf planet’s surface, an angle selected to further minimize consumption of hydrazine.

“If the wheels continue to operate, then it allows us to have more lifetime,” Raymond said. “Right now, with the fuel on-board, we could last without wheels through the beginning of August, and with wheels possibly about a year from now. So there’s quite a bit of uncertainty, but what we are certain about is we can finish our primary mission.”

Russell told Spaceflight Now that the Dawn science team is still discussing plans for a potential extended mission.

If Dawn stays in its current orbit, it will likely run out of hydrazine fuel in early 2017, Russell said.

The spacecraft could be moved back to a higher orbit, where it will burn less hydrazine, to keep the mission going even longer in hopes of seeing changes on Ceres’ surface as it goes through a seasonal cycle, he said.

“One question we’re asking is what is the time scale for changes on the surface of Ceres? Maybe if we think we will see changes on the order of days to years there is an interest in keeping the mission going,” Russell said. “If the changes are only seen in millions of years, for example, we would have to ask whether it is worth it?”

Russell said the Dawn mission could receive funding for a few extra months without going through a peer review by a panel of independent scientists — called a senior review — if the extension is short-term and does not involve any major change in flight plan.

The senior review held every two years helps NASA determine which of its operating space missions deserve extensions, and which projects have diminishing returns.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.