As NASA quietly works on a lander that could accompany a $2 billion flyby probe to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, the head of the European Space Agency’s science program tells Spaceflight Now that Europe is ready to play a significant role in the project.

The goals of the ESA contribution would be decided by European scientists, but the agency has the funding for a piggyback probe costing up to 500 million euros, or nearly $550 million, according to Alvaro Gimenez, ESA’s director of science and robotic exploration.

NASA asked the European Space Agency last year whether it was interested in contributing to the Europa mission, and Gimenez said in an interview with Spaceflight Now that the answer is yes.

“We will participate with no cost to NASA by us contributing something equivalent to a half-billion euros in cost to ESA,” Gimenez said. “Now, where it goes depends on the cooperation.

“This is a NASA mission, and we are happy to be a junior partner with NASA,” Gimenez told Spaceflight Now in December. “It’s our natural partnership with the U.S., and we will be very happy to do it. Now, they have to tell us the profile of the mission, what they want to do, and where do we have a role. But certainly we would appreciate the opportunity.”

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of an interview with Alvaro Gimenez, ESA’s director of science and robotic exploration. Become a member today and support our coverage.

NASA officials say the design of the Europa spacecraft, which is still unnamed, has room for an extra 250 kilograms, or 550 pounds, of mass. With limited free space and mass aboard the Europa mission, the spacecraft may be able to accommodate a lander or a sizable ESA piggyback probe, but perhaps not both.

“We are ready and interested,” Gimenez said. “As I said to my colleague in the U.S., we cannot allow Americans to go to Europa without Europeans. We have to be part of it. We think that it is natural, but certainly we will not lead, so we have to wait.”

Gimenez said ESA is taking its cues from NASA on Europa, so Europe will wait for a formal invitation before making the next move, which could come as soon as this year in the form of a request for mission proposals from the European science community.

“In all the discussions we have had, NASA is very open to our cooperation, but again, they have to define it,” Gimenez said. “It is a complicated mission. For Europa, in particular, we need a lot of mass. This is a very harsh environment (due to high radiation doses at Jupiter).”

Engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, where the Europa mission management team is based, are studying how to build and deploy a small lander that could descend to Europa’s perilous icy surface.

The lander concept is backed by Rep. John Culberson, a Texas Republican who chairs the House spending subcommittee responsible for writing NASA’s budget. Culberson has led efforts in Congress to start a Europa mission, and NASA agreed last year to approve development of the project, which is expected to cost about $2 billion, not counting a landing craft or other daughter satellites that could be tacked on to the mothership.

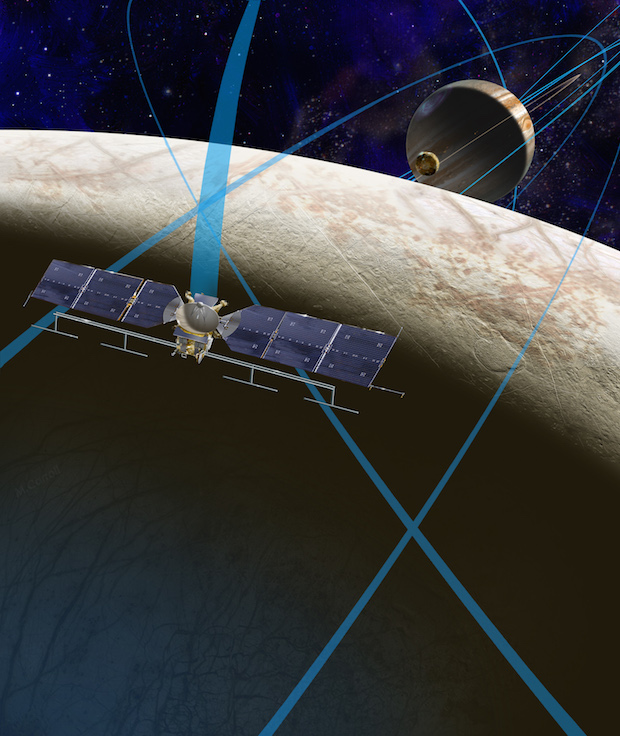

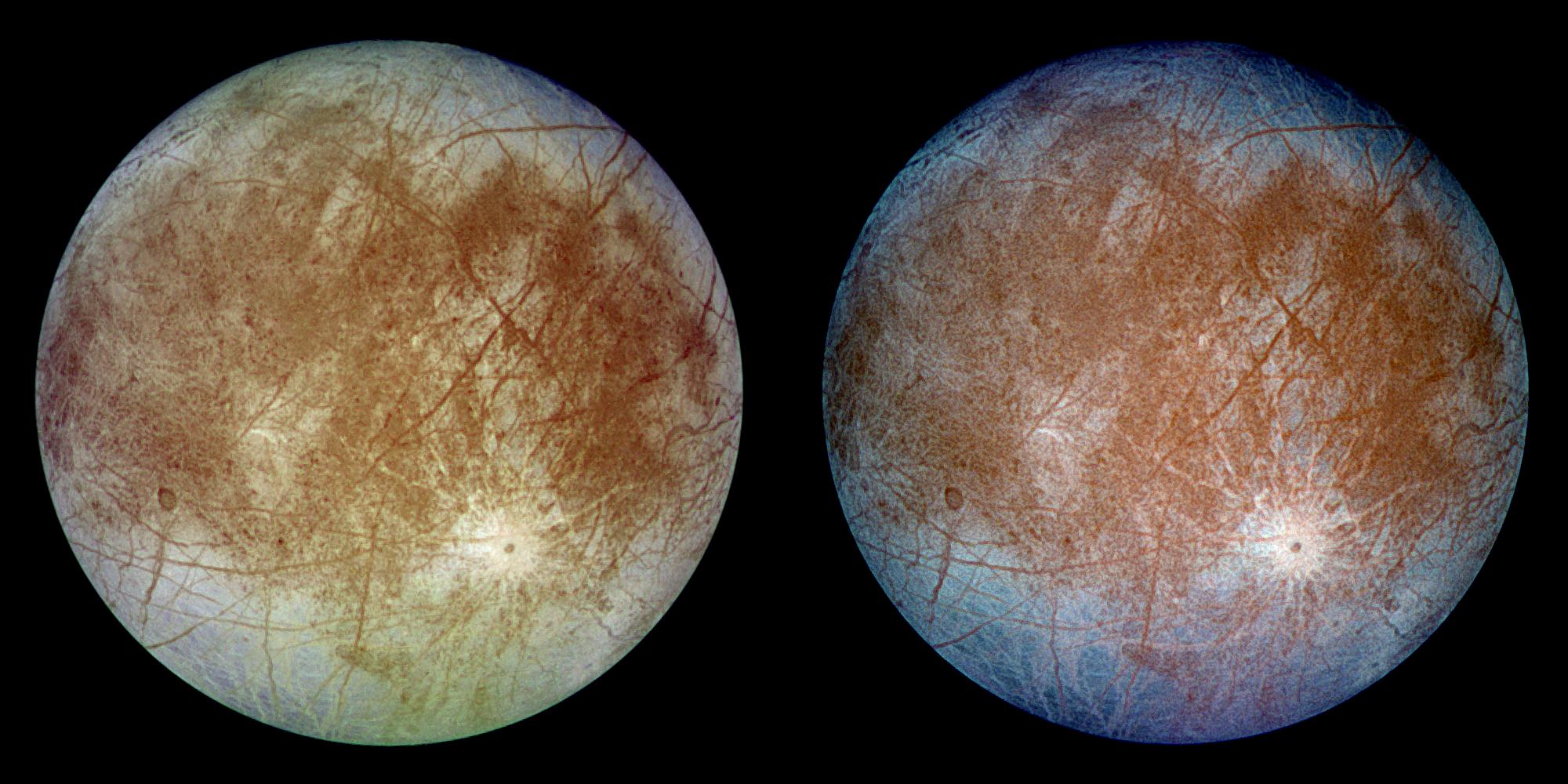

The solar-powered spacecraft is expected to launch no sooner than 2022, then slip into orbit around Jupiter on a trajectory to make up to 45 flybys of Europa, which spans more than 3,100 kilometers (1,900 miles) in diameter and harbors a global ice sheet floating on top of an ocean of liquid water.

Scientists place Europa at or near the top of locations in the solar system to search for life, and a survey released by the National Research Council in 2011 ranked a potential Europa mission as the second-highest planetary science priority for NASA, after a rover set for launch in 2020 to collect samples on Mars for eventual return to Earth.

After NASA formally kicked off the Europa project last year, the space agency selected nine scientific instruments to be fitted to the spacecraft.

NASA still has not endorsed the lander idea, with senior leaders questioning whether a lander should go to Jupiter with the Europa mission, according to Ars Technica.

“My scientific community, the people who do mission planning, say we need to go and do a little research with the first mission to Europa to determine whether that’s a place we want to send a lander,” said NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden in a November interview with Ars Technica. “That’s the point of our big disagreement with Congressman Culberson right now. He wants a multibillion dollar Europa mission that has a lander on the first flight and everything. Our belief is that that is imprudent from a scientific perspective.”

But with Culberson in charge of funding, Congress appears ready to release the money required to pay for a lander. An appropriations bill passed by Congress and signed into law in December said the Europa mission should include a lander.

NASA received $175 million in this year’s budget earmarked for the Europa mission, nearly six times more than the White House’s $30 million request. With the funding in the 2016 budget, Congress has given NASA about $430 million for the mission over the last four years.

Officials are not sure of the cost of landing on Europa, but ESA managers concluded last year that a lander could not be developed with the approximately $550 million Europe is willing to spend on a ridealong mission.

Gimenez he prefers for ESA to make a “real contribution” to the Europa mission, something more than providing an instrument for the spacecraft’s science payload.

“It would be up to a half-billion (euros), which is not peanuts,” Gimenez said. “But a mission like that would cost much more on its own. That is why we cannot lead, because we do not have the capability to bring something like that to Jupiter, and to do it fast. You need a huge rocket to do that.”

NASA intends to launch the Europa mission aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket or the agency’s huge Space Launch System. A launch aboard the SLS, several times more expensive than an Atlas 5 flight, could shave three years off the journey from Earth to Jupiter, allowing the craft to make the trip in less than two years.

Two studies commissioned by ESA’s future missions office last year identified two possible add-ons to NASA’s Europa spacecraft.

One of the concepts is a 250-kilogram (550-pound) daughter satellite that could release from the NASA mothership after it arrives at Jupiter. The European probe would conduct flybys to collect data on Europa or Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io independent of, or perhaps in collaboration with, the NASA spacecraft.

Another mission evaluated last year was a probe that could separate from the NASA-built spacecraft for a high-velocity impact on Europa’s frozen crust, where it would burrow into the moon’s subsurface and assess Europa’s habitability.

Fabio Favata, head of ESA’s science planning and community coordination office, told Spaceflight Now that the list of candidate missions Europe could develop to fly with NASA’s Europa probe is not limited to those two concepts.

Gimenez said ESA is prepared to issue a special call for proposals for a medium-class mission under the agency’s Cosmic Vision program as soon as this year. ESA periodically solicits proposals for small, medium and large science missions from Europe’s research community.

A large-class mission to Jupiter already selected by ESA is set for launch in 2022 aboard an Ariane 5 rocket, aiming to enter orbit around the giant planet’s moon Ganymede in the early 2030s.

The call would have a special emphasis on Europa, but any space science mission could be proposed and be eligible for the competition, according to Favata.

But the extent of ESA’s role in the mission, if any, could hinge to the lander outlined in the NASA budget.

“We have to wait a little bit because they are still in a very preliminary phase of studies, but we are already in conversations with NASA and JPL about different options,” Gimenez said. “Then we have to see.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.