SpaceX launched a pair of four-ton Intelsat communications spacecraft from Cape Canaveral at twilight Saturday evening, two days later than planned after back-to-back scrubs, on the third flight of a Falcon 9 rocket this week.

The Falcon 9 rocket lit nine kerosene-fueled Merlin 1D engines and thundered away from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station at 7:05 p.m. EDT (2305 GMT) Saturday. Thrust vector controls pivoted nine main engines to steer the 229-foot-tall (70-meter) rocket due east from pad 40, and the Falcon 9 raced through the speed of sound in less than a minute.

Saturday’s mission, carrying Intelsat’s Galaxy 33 and 34 video relay satellites, marked the third Falcon 9 flight in a little more than three days, following back-to-back launches Wednesday.

A SpaceX launch from Florida on Wednesday carried a four-person crew to the International Space Station, and was followed seven hours later by another Falcon 9 launch from California with a batch of Starlink internet satellites — the shortest interval between two Falcon 9 flights to date.

The Intelsat mission was originally supposed to blast off Thursday, but automated systems ordered a last-minute abort after detecting a small helium leak. SpaceX called off another launch attempt Friday before setting up for the countdown Saturday.

The Falcon 9 rocket took off from Florida’s Space Coast about five minutes after sunset, providing a colorful backdrop for the Falcon 9’s climb into space. The first stage shut down its engines about two-and-a-half minutes into the flight, and separated to continue downrange on an arcing trajectory toward SpaceX’s rocket landing platform.

The Falcon 9’s second stage ignited a single Merlin engine to power the rocket the rest of the way into orbit. The two halves of the rocket’s nose shroud jettison a few moments later. The four major components of the rocket — the booster stage, upper stage, and two pieces of the payload fairing — appeared to the naked eye as individual white dots moving across the evening sky, illuminated by the last rays of sunlight at the edge of space.

Cold gas thrusters re-oriented the booster and payload fairing halves for re-entry back into the atmosphere. The booster dropped back toward the Atlantic Ocean and guided itself toward an on-target landing on the football field-size drone ship about 400 miles (640 kilometers) east of Cape Canaveral.

Here’s a replay of the spectacular launch of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral tonight with Intelsat’s Galaxy 33 and 34 satellites, beginning a twilight climb to orbit with nine Merlin 1D engines generating 1.7 million pounds of thrust. https://t.co/VpaBPm5mtb pic.twitter.com/pc6FofUFSe

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) October 8, 2022

It was the 14th flight for this booster, tying a record for SpaceX’s inventory of reusable rockets. Before Saturday, SpaceX had never launched such a well-used booster for a paying customer, only employing the most-flown rockets for the company’s own Starlink missions.

Intelsat officials said they were confident in the booster’s performance going into Saturday’s launch. When SpaceX started flying reused rockets in 2017, the company offered discounts to entice customers to sign up for a launch on a previously-flown booster. That’s no longer the case.

“It’s the same price if you’re the first or the 14th,” said Jean-Luc Froeliger, Intelsat’s senior vice president of space systems.

SpaceX has qualified its reusable Falcon 9 boosters for at least 15 missions, up from the 10-mission goal the company stated when it debuted the Block 5 booster — the latest iteration of the Falcon 9 — in May 2018, the trade magazine Aviation Week & Space Technology reported in June.

“They’re very impressive,” Froeliger, a longtime satellite industry manager, said of SpaceX. “They have found a model where their reusable first stage and reusable fairing allow them to launch on a very rapid cadence, they have two launch complexes here (in Florida), plus Vandenberg. So yes, they get a lot of business.”

Froeliger said SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launcher is the “workhorse of the industry” after SpaceX pioneered recovery and reuse of commercial rockets. After Saturday’s mission, the company has launched 46 times so far this year, far outpacing any of its rivals in the launch business.

With the booster’s work complete Saturday, the Falcon 9’s upper stage fired its engine two times to propel the Galaxy 33 and 34 payloads into an elliptical “sub-synchronous” transfer orbit with an apogee, or high point, ranging more than 10,000 miles above Earth.

A good landing confirmed by SpaceX for the Falcon 9 booster — designated B1060 — completing its 14th flight to space. The Falcon 9’s launch plume is seen on the western horizon from the drone ship.

Falcon 9’s upper stage now in a parking orbit.https://t.co/VpaBPm5mtb pic.twitter.com/87LxpfAb9n

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) October 8, 2022

Galaxy 33 and 34 were mounted on top of the other for the nearly 40 minute ride on the Falcon 9 rocket. Galaxy 33 separated from the rocket first, followed five minutes later by deployment of Galaxy 34.

Intelsat confirmed later Saturday evening that ground teams at Northrop Grumman, which manufactured the Galaxy 33 and 34 spacecraft, received the first radio signals from the new satellites. The signal acquisition allowed engineers to confirm the satellites were healthy and in the correct orbit following launch.

The two Intelsat television broadcasting satellites are heading for geostationary orbit as part of a multibillion-dollar program to clear C-band frequencies for 5G wireless services. Galaxy 33 and 34 will use their own liquid-fueled thrusters to raise their orbits to geostationary altitude around 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator, a process expected to take 10 or 11 days, Froeliger said.

At that altitude, the orbital velocity of the satellites will match the rate of Earth’s rotation, giving them a constant view of the same geographic region of the planet.

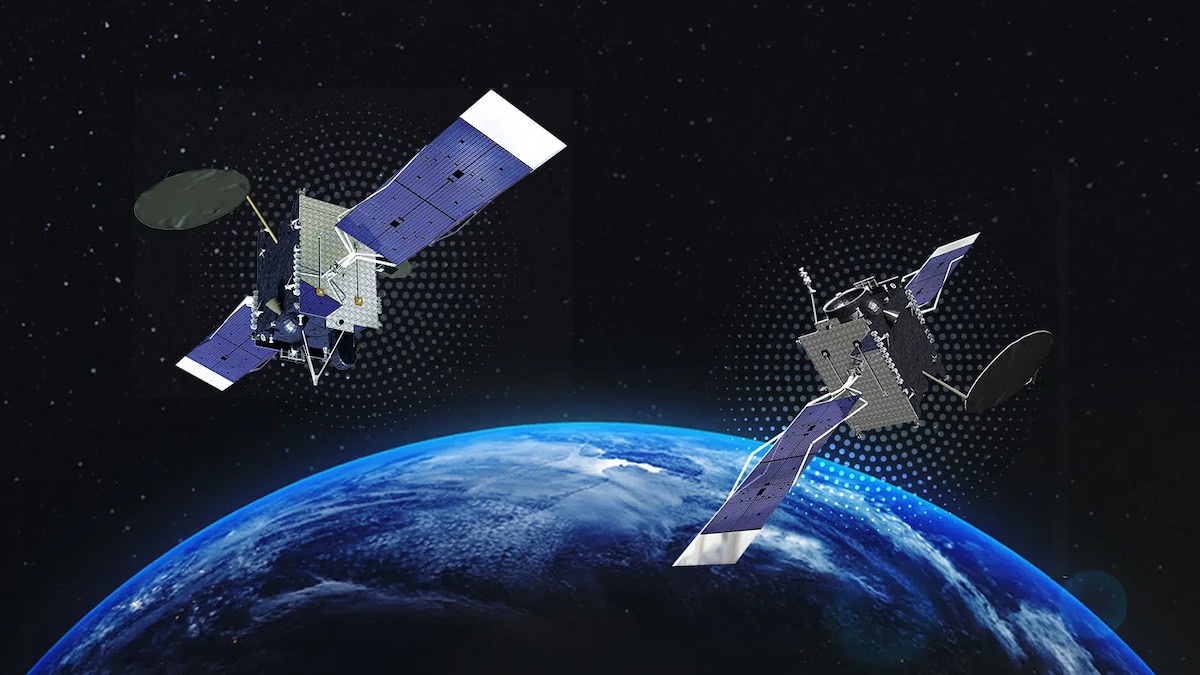

The Galaxy 33 and 34 satellites are setting off on 15-year missions to relay C-band video and television programming for media networks and cable providers across North America. They will replace two aging Intelsat satellites, Galaxy 12 and Galaxy 15, that have been in space since 2003 and 2005.

Intelsat expects the new satellites to enter service in early November and early December, once they reach their operating positions in geostationary orbit and complete post-launch checkouts.

The two satellites are similar, but not identical.

Galaxy 33, which weighed 8,057 pounds (3,654 kilograms) fully fueled for launch, carries a C-band communications payload, plus steerable Ka-band and Ku-band beams. The 8,146-pound (3,695-kilogram) Galaxy 34 spacecraft is a purely C-band satellite.

Galaxy 33 will replace the Galaxy 15 communications satellite in an operating position at 133 degrees West longitude. Intelsat lost control of Galaxy 15 in August after it was likely damaged during a geomagnetic storm, the company said. Galaxy 15 was already due for replacement before Intelsat lost contact with spacecraft.

Intelsat plans to fly the Galaxy 34 satellite to 129 degrees West longitude, where it will replace Galaxy 12.

Here’s the view from the Falcon 9 rocket 1,000 miles over the Indian Ocean, showing deployment of Intelsat’s Galaxy 34 satellite moments ago. Galaxy 33, which separated a few minutes earlier, is visible in the distance against the blackness of space. https://t.co/VpaBPmnvHj pic.twitter.com/KjZxa0dPS5

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) October 8, 2022

Froeliger said brand names like HBO, Starz, Discovery Channel, Disney Channel, and Diamond Sports Group broadcast programming through Intelsat’s Galaxy satellites.

“These satellites are C-band satellites for North American customers, primarily media,” Froeliger said. “They’re part of a seven-satellite buy that we did in 2020 to replace some of our Galaxy satellites.”

Galaxy is Intelsat’s brand name for satellites covering North America.

“Those seven satellites are not only replacing existing Galaxy satellites for our North American media customers, but they’re also helping clear the lower end of the C-band spectrum over the United States, so they are very, very important satellites for us,” Froeliger said in a pre-launch interview with Spaceflight Now.

Galaxy 33 and 34 are part of a program to redirect satellite television communications services to a different part of the C-band spectrum, following the Federal Communications Commission’s decision in 2020 to clear 300 MHz of spectrum for the roll-out of 5G mobile connectivity networks.

The FCC auctioned U.S. C-band spectrum — previously used for satellite-based video broadcast services to millions of customers — to 5G operators, which are paying satellite operators like Intelsat and SES through multibillion-dollar compensation agreements. SES and Intelsat purchased new C-band broadcasting satellites to function in the narrower swath of spectrum.

In 2020, SES ordered six new C-band satellites, including a spare, and Intelsat procured seven C-band satellites. SES launched their first new C-band satellite as part of the program in June on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, then added two more with a launch on ULA’s Atlas 5 rocket from Cape Canaveral earlier this week. The SpaceX launch for Intelsat Saturday is the latest step in the C-band clearing program.

“The lower 300 MHz of (C-band frequencies) have been optioned to the mobile network operators, such as Verizon, T-Mobile, and AT&T,” Froeliger said. “So we need these satellites to be able to move our customers and move them to the upper band. They’re replacing older satellites, and at the same time allowing the customers to be moved to the upper frequencies to free up the lower frequencies.”

Satellite telecom providers have also installed filters and other equipment on ground antennas to enable the changeover to higher C-band frequencies.

Intelsat has five more C-band satellites left to launch after Galaxy 33 and 34. The next pair of C-band satellites, Galaxy 31 and 32, are scheduled to launch as soon as Nov. 5 from Cape Canaveral on another SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

For that mission, SpaceX will not recover the Falcon 9 booster, committing all of the rocket’s propellant to sending Galaxy 31 and 32 into as high of an orbit as possible. “Those satellites, Galaxy 31 and 32, are built by Maxar. They’re a little heavier, so we decided go for an expendable launch to get the extra performance,” Froeliger said.

“You pay extra when it’s expendable,” Froeliger said. “From a business point of view, you may also get a booster that has flown many times that they may retire anyhow, but you’re still paying because you pay for the expendable.”

Another pair of C-band satellites — Galaxy 35 and 36 — are booked to launch on a European Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana in December. And the last of the group, Galaxy 37, will launch as the sole passenger on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket next year.

With Galaxy 33 and 34 successfully launched, SpaceX’s next mission is scheduled for no earlier than Oct. 13 with the Hotbird 13F communications satellite for Eutelsat. Ground teams are finishing up preparations on the Airbus-built Hotbird 13F satellite, which was delivered to Cape Canaveral from its factory in Toulouse, France, last month.

SpaceX transferred the Falcon 9 booster for the Hotbird 13F mission to the hangar at pad 40 earlier this week.

Later this month, SpaceX plans to launch its fourth Falcon Heavy rocket with a secret payload for the U.S. Space Force. The triple-body rocket, made by combining three Falcon rocket boosters together, will blast off from pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center no earlier than Oct. 28. It will be the first Falcon Heavy launch in more than three years.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.