Astra is preparing to launch the first of three straight dedicated missions for NASA this weekend at Cape Canaveral to deploy six shoebox-size hurricane research satellites, helping pioneer a new paradigm of riskier but less expensive science missions.

The commercial launch company, geared toward the burgeoning small satellite industry, won a $7.95 million contract last year to haul NASA’s six TROPICS spacecraft into orbit using three rockets.

The first of the three TROPICS missions is set for liftoff during a two-hour window opening at 12 p.m. EDT (1600 GMT) Sunday. Forecasters predict stormy weather at the launch site, with a greater than 50% chance conditions could prevent liftoff. Conditions should improve Monday, according to the official launch weather outlook.

Astra delivered the rocket to Florida’s Space Coast last month from its California factory, then completed a test-firing of the booster’s five engines at Space Launch Complex 46, a commercially-operated facility near the easternmost extent of Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

The first two TROPICS satellites are mounted inside a deployer on top of the 43-foot-tall (13.1-meter) Astra launcher, which the company calls Rocket 3.3, or tail number LV0010.

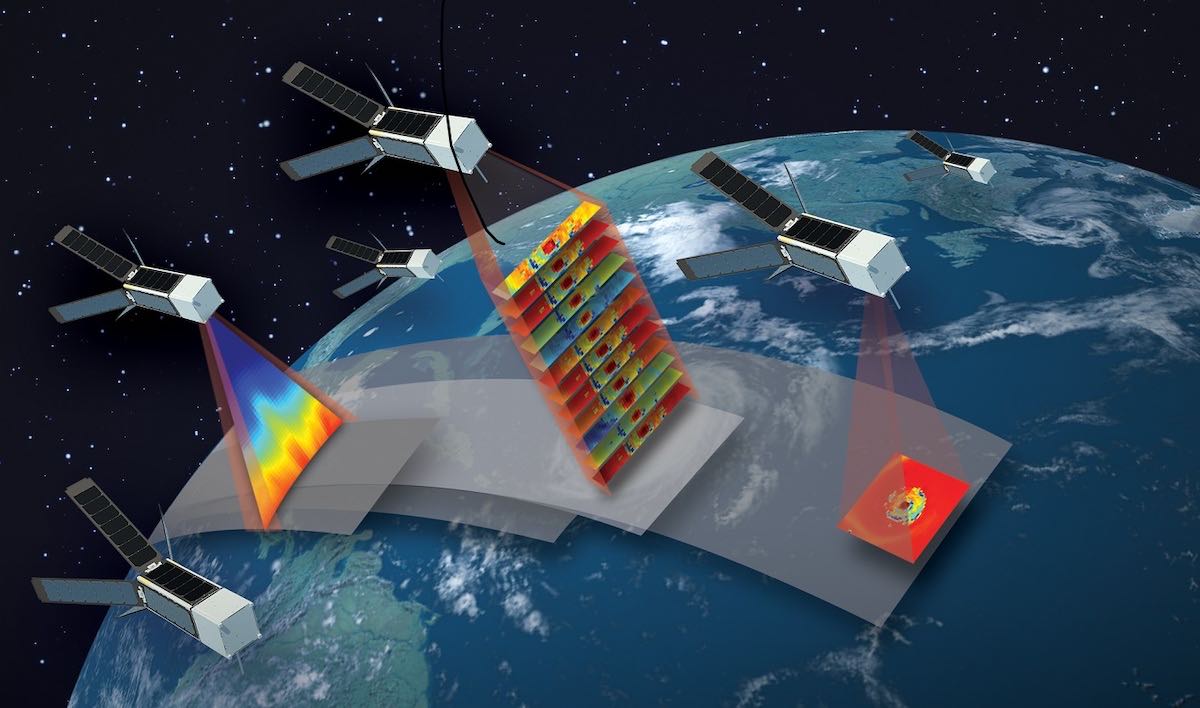

“We’re trying to make improved observations of tropical cyclones,” said William Blackwell, principal investigator for the TROPICS mission from MIT Lincoln Laboratory. “And what we’re really trying to characterize is the fundamental thermodynamic environment around the storm. So that’s things like the temperature, and the amount of moisture and precipitation intensity, and the structure around the storm.

“Those are important variables because they can be related to the intensity of the storm, and even potential for future intensification,” Blackwell said in Friday in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “So we’re trying to make those measurements with relatively high revisit. That’s really the key new feature that the TROPICS constellation provides, is improved revisit of the storms.

“We’ll have six satellites orbiting, and one satellite will work to make a nice image of the storm, and then the next satellite will orbit closely behind it about an hour behind,” Blackwell said. “So we’ll get, roughly every hour, a new image of the storm, and that’s about a factor of five-to-eight better than what we get today. With these new measurements of rapidly updated imagery, we hope that that will help us understand the storm better, and ultimately lead to better forecasting of the hurricane track and intensity.”

TROPICS stands for Time-Resolved Observations of Precipitation structure and storm Intensity with a Constellation of Smallsats. The mission has a total cost of approximately $30 million, according to NASA.

Each TROPICS satellite has a single instrument. A microwave radiometer, about the size of a coffee cup and spinning 30 times per minute, will create images of tropical cyclones, collect temperature measurements, and gather vertical profiles of moisture through the atmosphere.

“I love TROPICS, just because it’s kind of a crazy mission,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, head of NASA’s science mission directorate. “Think of six CubeSats doing science, looking at tropical storms with a repeat time of 50 minutes.”

“NOAA and the Europeans and many others have been flying passive microwave radiometers for decades, and these are big, expensive instruments,” Blackwell said. “What we’ve done with TROPICS is miniaturize the electronics to make them much smaller.

“The entire satellite for TROPICS, one of them weighs about 10 pounds, and is about the size of a loaf of bread,” Blackwell said. “So these are relatively inexpensive to build and test, and we can make them fairly rapidly, and they’re relatively inexpensive to launch.”

The TROPICS satellites were built by Blue Canyon Technologies in Boulder, Colorado. Their small size makes them a good fit for Astra, which can deliver about 110 pounds (50 kilograms) of payload to a 310-mile-high (500-kilometer) orbit. Astra’s rocket is the smallest orbital-class launcher currently flying.

Astra will launch two TROPICS satellites at a time, flying missions at several-week intervals. If all goes well, the launches should be completed by the end of July.

The satellites will launch into orbit 357 miles (550 kilometers) above Earth, circling the planet at an angle 29.75 degrees to the equator. The low-inclination orbit will focus the TROPICS observations on hotspots for tropical cyclone development.

The second and third TROPICS launches — currently planned for late June and mid-July — will aim to deploy the next four satellites into precise orbital planes, giving the constellation the proper spacing to enable regular flyovers of cyclones.

Many CubeSats ride to space on rideshare launches, allowing operators to take advantage of lower costs by bundling their payloads on a single large rocket. But the TROPICS satellites need dedicated launches to reach their precise orbital destinations.

“We want to space out the spacecraft as much as we can, and want to keep them over the tropical cyclone belt,” Blackwell said. “This overall configuration lets us do that, but it requires three separate dedicated launchers.”

Astra beat out bids from SpaceX, Rocket Lab, Virgin Orbit, and Momentus, largely due to their lower-cost proposal, according to NASA.

“NASA selected Astra because of our unique ability to get to three different orbital planes in a very short period of time, at a low cost,” said Martin Attiq, Astra’s chief business officer. “So being able to launch three different times for $8 million is unprecedented.”

Founded in 2016, Astra aims to eventually launch daily missions to carry small satellites into orbit for a range of customers, including the U.S. military, commercial companies, and NASA. The company has successfully reached orbit in two of six tries.

Astra’s most recent flight in March marked the first time the company placed functioning satellites into orbit, following a liftoff from Kodiak Island, Alaska. The previous Astra launch in February, which departed Cape Canaveral, failed to place a payload of NASA-sponsored CubeSats into orbit.

NASA officials are aware of the risk of flying satellites on a new, relatively unproven launcher. TROPICS is part of NASA’s Earth Venture program, a series of cost-capped missions designed for Earth science research. NASA assumes more risk for Venture-class missions.

“Only four of the spacecraft need to work, so two rockets need to work,” Zurbuchen said. “This is a different risk level than what we do in so many other things in which we kind of focus, flatten the risk, and pound it down as much as we can. And that is deliberate. It’s deliberate because speed matters when you’re in the innovation game, and we want new capabilities and new assets and new tools.”

NASA selected TROPICS for development in 2016.

“We’ve designed the mission from the ground up to build in some robustness to failure,” Blackwell said. “The choice of six satellites was made to give us some margin. We only needed four to meet our baseline requirements, so we can tolerate failures of the satellite or failures of the launch, or whatever, and we can still meet our requirements.”

Astra’s first launch with two TROPICS satellites will begin with the ignition of Rocket 3.3’s five kerosene-fueled engines at pad 46. The Delphin engines will drive the launcher off the pad with 32,500 pounds of thrust, powering the rocket downrange to the east-northeast from Cape Canaveral.

First stage engine cutoff is expected three minutes after liftoff, followed by separation of the rocket’s payload shroud, which covers the upper stage and the TROPICS payloads during the climb through the atmosphere. Then rocket’s booster stage will jettison to fall into the Atlantic, allowing the upper stage to ignite for a five-minute burn to accelerate to orbital velocity.

Deployment the TROPICS satellites is scheduled at T+plus 8 minutes, 40 seconds, according to a mission timeline posted by Astra.

The satellites will unfurl solar panels to begin generating electricity, and ground teams will run the TROPICS spacecraft through tests and checkouts.

If the three TROPICS launches get off the ground as scheduled, the satellites should all be collecting by August, just in time for the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season, according to Will McCarty, NASA’s program scientist for the mission. The mission is designed for at least one year of science observations.

“We’re, of course, highly motivated to get the data out as soon as we can because we’re going to be in the throes of Atlantic hurricane season, so there’s going be a lot of demand for that data,” Blackwell said.

A pathfinder satellite for the TROPICS mission launched last June on a SpaceX rideshare mission, and has performed well in orbit, collecting test measurements of temperature and moisture over multiple tropical cyclones, including Hurricane Ida before it made landfall in Louisiana.

The experience with the TROPICS pathfinder satellites builds confidence that the six operational satellites will work, McCarty said.

“Our requirement from NASA is to collect science data for one year, and we hope to go longer than that,” Blackwell said. “There are some cases where these CubeSats are lasting three years, or even more, so we hope it will be significantly longer than than the one-year requirement.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.