EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated at 8 p.m. with Washington Post quote.

The head of NASA’s human spaceflight programs has abruptly resigned, announcing his departure from the space agency two days before before he was to chair a crucial readiness review ahead of the launch of the first crewed U.S. space mission in nearly a decade.

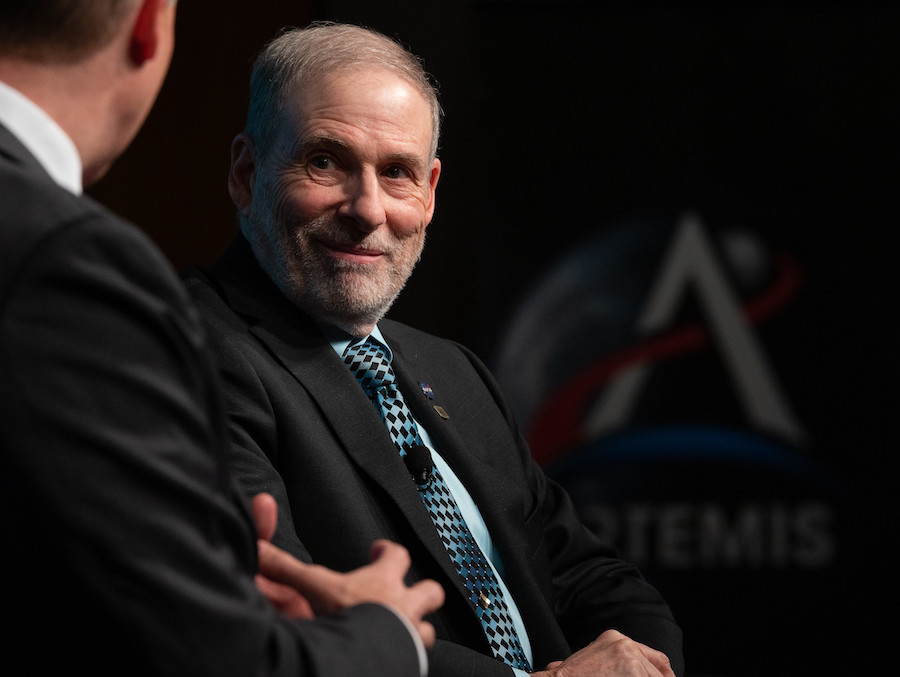

Doug Loverro joined NASA in December after decades managing military space programs, and his tenure at NASA lasted just six months. He replaced Bill Gerstenmaier, who was removed from his post by NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine last July in a shakeup of the space agency’s human spaceflight efforts.

In a statement Tuesday, NASA said Loverro resigned from the agency effective Monday. NASA did not specify a reason for Loverro’s departure, which happened eight days before the first launch of U.S. astronauts from the Kennedy Space Center in nearly nine years.

Loverro was to chair the Flight Readiness Review Thursday for the mission of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft, which will carry astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken to the International Space Station on a test flight designated Demo-2, or DM-2.

Industry sources told Spaceflight Now that Loverro resigned due to issues during the procurement of NASA’s Human Landing System for the Artemis program, which aims to develop crewed moon landing vehicles to carry astronauts to the lunar surface by the end of 2024, an aggressive schedule set by the Trump administration.

The Washington Post reported Tuesday that Loverro said in an interview his resignation had “nothing to do” with the Crew Dragon flight scheduled for next week.

“It had to do with moving fast on Artemis, and I don’t want to characterize it in any more detail than that,” Loverro told the Washington Post.

“Loverro hit the ground running this year and has made significant progress in his time at NASA,” Bridenstine said in a statement. “His leadership of HEO (Human Exploration and Operations) has moved us closer to accomplishing our goal of landing the first woman and the next man on the moon in 2024.

“Loverro has dedicated more than four decades of his life in service to our country, and we thank him for his service and contributions to the agency,” Bridenstine said.

Steve Jurczyk, NASA’s associate administrator and and most senior career civil servant, will take Loverro’s place as chair of the Crew Dragon Demo-2 Flight Readiness Review, a NASA official said.

Loverro was also scheduled to participate in a press conference Thursday after the conclusion of the Flight Readiness Review. Bridenstine is expected to take media questions Wednesday at the arrival of Hurley and Behnken at Kennedy to prepare for the final week before their launch on top of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

In an all-hands letter to NASA employees, Loverro wrote that he is leaving the agency “because of his personal actions.”

He wrote that he “truly looked forward to living the next four-plus years with you as we returned Americans to the surface of the moon and prepared for the long journey beyond. But that is not to be.”

“Throughout my long government career of over four and a half decades I have always found it to be true that we are sometimes, as leaders, called on to take risks,” Loverro wrote in the letter, dated Tuesday. “Our mission is certainly not easy, nor for the faint of heart, and risk-taking is part of the job description.

“The risks we take, whether technical, political, or personal, all have potential consequences if we judge them incorrectly,” he wrote. “I took such a risk earlier in the year because I judged it necessary to fulfill our mission.

“Now, over the balance of time, it is clear that I made a mistake in that choice for which I alone must bear the consequences,” Loverro wrote. “And therefore, it is with a very, very heavy heart that I write to you today to let you know that I have resigned from NASA effective May 18th, 2020.”

In the letter, Loverro told employees that he is not leaving NASA because of any performance issues within the human spaceflight workforce.

“If anything, your performance and those plans make everything we have worked for over the past six months more attainable and more certain than ever before,” Loverro wrote. “My leaving is because of my personal actions, not anything we have accomplished together.

Bridenstine announced Loverro last October as the new associate administrator for NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate. Loverro officially joined NASA in December, overseeing a key time in the agency’s human spaceflight programs as NASA moved closer to launching astronauts on U.S. vehicles for the first time since the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011.

Loverro led the human spaceflight directorate in the wake of a botched test flight of Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule in December, in which the spacecraft failed to dock with the International Space Station due to a mission timing software error. The spacecraft safely landed in New Mexico two days after launch, but Boeing ground teams had to overcome another potentially catastrophic software miscue before re-entry.

Loverro also managed NASA’s Artemis program, in which the agency aims to land humans on the south pole of the moon by the end of 2024.

Ken Bowersox, Loverro’s deputy, will take over as acting chief of NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Directorate. Bowersox filled the same role last year between Gerstenmaier’s reassignment and Loverro’s arrival at NASA.

Bowersox is a retired U.S. Navy test pilot, and a veteran of five space missions. He commanded two space shuttle flights, and led the Expedition 6 crew on the International Space Station in 2002 and 2003.

“NASA has the right leadership in place to continue making progress on the Artemis and Commercial Crew programs,” Bridenstine wrote.

Garrett Reisman, a former NASA astronaut and manager in SpaceX’s Dragon program, tweeted that timing of Loverro’s resignation was “not good,” but expressed confidence in Bowersox, another former SpaceX manager.

Timing on this is not good, but I’d be a lot more concerned if it weren’t for the fact that Sox is more than capable of overseeing this important week in Human Spaceflight. His deep experience at @NASA and @SpaceX makes him the ideal replacement for Loverro, actually. https://t.co/ioF3z39UpH

— Garrett Reisman (@astro_g_dogg) May 19, 2020

“Next week will mark the beginning of a new era in human spaceflight with the launch of NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley to the International Space Station,” Bridenstine wrote, adding that NASA has “full confidence” in the Commercial Crew team.

“This test flight will be a historic and momentous occasion that will see the return of human spaceflight to our country, and the incredible dedication by the men and women of NASA is what has made this mission possible,” Bridenstine wrote.

Loverro and his team conducted a major program status assessment earlier this year, recommending a reorganization of the human spaceflight directorate in order to meet the 2024 schedule for a crewed landing on the moon.

NASA selected three contractors April 30 to design new human-rated lunar landers for the Artemis program. The agency selected industry teams led by Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX to continue work on lunar lander concepts during an initial 10-month work period.

Last week, Loverro told the NASA Advisory Council’s Human Exploration and Operations Committee that officials performing the Artemis program status assessment recommended down-selecting to two lunar lander contractors early in development. According to a chart in Loverro’s presentation last week, the early down-select would “maximize resources” for the remaining contractors.

Bridenstine told Spaceflight Now in late April that he hoped NASA could keep all three companies in the mix.

“We are hopeful that we can go forward with all three,” Bridenstine said. “It doesn’t mean that we will, but I think that each one of them is so unique and different, that we want to see what are the best capabilities that each of these companies bring to the table that we can take advantage of. That’s what this base period is really all about.”

“As far as down-selecting, if we did down-select, we would probably down-select to two,” Bridenstine said. “We wouldn’t probably go below two. That’s because there’s a difference between going fast and going sustainably, and a lot of these different companies have different solution sets for achieving each of those requirements.”

Loverro agreed that going forward with two contractors would allow the companies to remain in a competition, potentially driving down costs to NASA in the process.

“Clearly, we’d love to go ahead and keep three on-board, but the budget will probably require that we go ahead and move to fewer contractors,” Loverro told Spaceflight Now last month. “Two is probably the least that we’ll get to. We need to keep competition going. Obviously, that’s critically important as well. And we need to make sure that we are able to focus each contractor on the objectives that we believe are most important for them.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.