A Vega rocket fired into orbit Thursday night from French Guiana with Italy’s PRISMA hyperspectral Earth-imaging satellite, commencing a busy period for the Vega launcher program as engineers prepare for the debut of the more powerful Vega-C booster in early 2020 and study a lighter variant to better compete in the growing smallsat launch market.

The 98-foot-tall (30-meter) rocket fired its solid-fueled first stage at 10:50:35 p.m. French Guiana time Thursday (9:50:35 p.m. EDT; 0150:35 Friday), instantly sending the launcher into the late-night sky over the Guiana Space Center, a tropical space base on the northeastern coast of South America.

The Vega’s first stage nozzle swiveled to align the rocket with a trajectory north from French Guiana, propelling the launcher faster than the speed of sound within 30 seconds as the booster ramped up to full power with nearly 700,000 pounds of thrust. The first stage consumed its pre-packed solid propellant in less than two minutes, and high-power tracking cameras showed the booster dropping away as the Vega’s second stage ignited to continue the flight into space.

The second and third stage motors completed their burns in less than six-and-a-half minutes, and the Vega’s fourth stage — known as the Attitude and Vernier Upper Module — ignited its liquid-fueled engine two times to deliver the 1,937-pound (879-kilogram) PRISMA spacecraft into orbit.

The Vega rocket’s guidance computer aimed to release PRISMA in a 382-mile-high (615-kilometer) orbit inclined 97.9 degrees to the equator, and officials declared the launch a success after the upper stage deployed its sole payload around 54 minutes after liftoff.

“Arianespace is delighted to announce that PRISMA has been separated as planned on its targeted sun-synchronous orbit,” says Luce Fabreguettes, Arianespace’s executive vice president of missions. “There was no better way for Vega to start the year 2019 than with its 14th success in a row. Congraulations to all.”

PRISMA was the 600th satellite launched by Arianespace, and the 70th Earth observation satellite launched by Europe’s rocket family, Fabreguettes said in a speech after Thursday night’s mission.

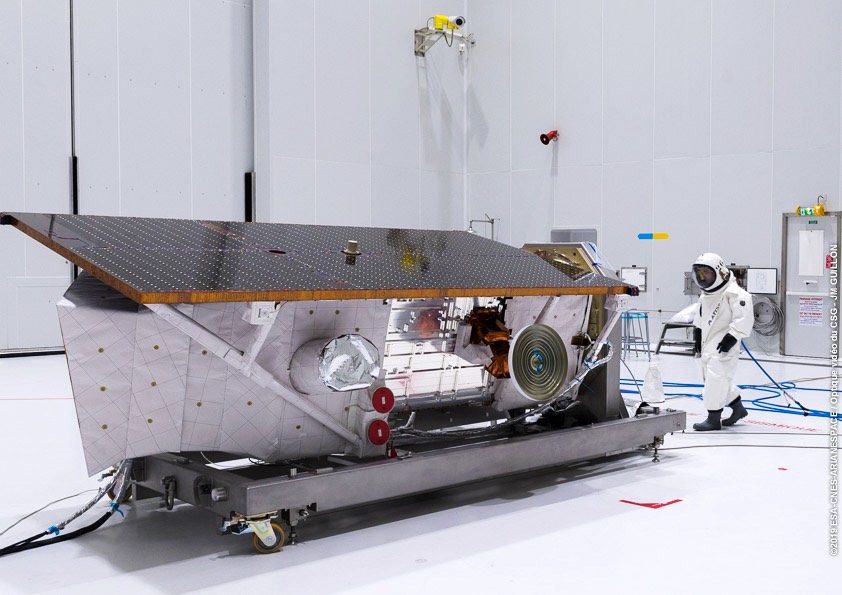

The $143 million (126 million euro) PRISMA mission is led by the Italian space agency, known as ASI, and is designed to monitor the environment, track pollution and water quality, and chart the growth of forests and crops. After a thorough checkout in orbit, PRISMA is scheduled to begin a five-year operational mission beginning in June, according to an ASI spokesperson.

PRISMA stands for PRecursore IperSpettrale della Missione Applicativa, or the Hyperspectral Precursor and Application Mission. The satellite will collect imagery of Earth in numerous spectral bands, breaking the sunlight reflected off the planet’s oceans, forests, and cities into 240 parts to resolve parameters such as plant health, soil erosion and chemistry, oil spills, water salinity, and natural resources.

The satellite’s instrument combines the hyperspectral sensor, with sensitivity in 239 bands, with a medium-resolution panchromatic, or black-and-white, camera providing context views.

“PRISMA is a fully Italian Earth observation mission based on a single satellite carrying a hyperspectral imager that will characterize the Earth’s surface on a global scale, extracting geochemical, biochemical and geophysical parameters, providing unique information on the status and evolution of our planet,” said Francesco Longo, PRISMA’s project manager at ASI.

The Italian space agency started working on the PRISMA mission after the cancellation of a previous hyperspectral imaging satellite named HypSEO in the early 2000s. PRISMA itself was delayed several years as engineers developed the satellite and its payload, both of which are based on new designs.

“Hyperspectral imaging is a novelty of remote sensing technology that acquires image data in hundreds of narrow continuous bands from the visible to the shortwave infrared,” Longo said. “Each individual pixel of the hyperspectral image contains a continuous spectrum of the solar radiation reflected by the surface. These spectra include absorption features which can be interpreted as spectral fingerprints of Earth’s elements. That allows the identification of mineral types and soils … vegetation types and conditions, and to detect pollutants in water and air.”

Italian officials described PRISMA as the most capable environmental satellite of its kind, combining the hyperspectral sensor and electro-optical camera into one instrument.

“We are proud to deliver the first European hyperspectral satellite to ASI,” said Roberto Aceti, managing director of OHB Italia, which built the PRISMA spacecraft. “This satellite will open new frontiers on services and applications.”

PRISMA’s black-and-white camera has a resolution of about 16 feet, or 5 meters, and the hyperspectral sensor will analyze the physical and chemical properties of Earth’s surface in 98-foot (30-meter) sections. The mission’s Earth-observing payload was supplied by Leonardo Airborne and Space Systems, an Italian company.

“It was a big technological challenge for us,” said Massimo Cosi, PRISMA payload project manager at Leonardo.

According to ASI, the PRISMA satellite will be able to collect up to 223 images per day, each covering 18.6-mile by 18.6-mile (30-kilometer by 30-kilometer), with the ability to maneuver and point its camera up to 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) either side of its orbital track.

Users of PRISMA data will include scientists, urban planners, the agricultural sector, and Italian national security officials.

PRISMA’s launch begins busy year for Vega rocket program

Thursday night’s launch was the first of up to four Vega rocket launches scheduled this year.

The next Vega launch is scheduled for June with the Falcon Eye 1 surveillance satellite for the United Arab Emirates, officials said this week. Later this year, two more Vega rockets launch from French Guiana, one as soon as August carrying 42 small satellites on a rideshare mission, and another in the November timeframe with the Falcon Eye 2 spacecraft, a twin of Falcon Eye 1.

The Vega rocket is built by a European industrial consortium led by the Italian company Avio, which is finishing the development of the new Vega-C launcher, featuring uprated rocket motors and a large payload shroud to accommodate bigger satellites.

Giulio Ranzo, Avio’s CEO, said assembly of the first Vega-C rocket on its launch pad in French Guiana will begin before the end of the year. Workers will first finish modifying the launch pad for the Vega-C, which is wider and stands around 16 feet (5 meters) taller than the current Vega configuration.

Ranzo told Spaceflight Now that the Vega-C’s first launch, which was scheduled at the end of 2019, was pushed back to early 2020 to allow Arianespace to conduct four Vega missions this year. Preparations for the inaugural Vega-C flight are expected to take more time than for a typical Vega mission.

“Everything is all happening in the same place,” Ranzo said in an interview this week. “It’s obviously creating a little bit of congestion, so we can’t make everything happen at the same time. The development itself is perfectly on track.”

Managers from industry and the European Space Agency, which is funding most of the new rocket’s development costs, completed a critical design review for the Vega-C launcher earlier this month. The milestone cleared the way for full-scale production of flight hardware, Ranzo said.

“We were authorized to start manufacturing the flight assets, so we’re now in the course of manufacturing flight items,” he said. “So everything is going according to plan, as far the development is concerned. Obviously, putting it all together with a busy flight schedule for Vega, we cannot do everything at the same time.

“At the same time, if you consider that we started development of Vega-C only 36 months ago, it’s probably among the fastest rocket developments that we’ve ever seen. Quite frankly, we’re very happy about that.”

The current Vega configuration can deliver around 3,300 pounds (1,500 kilograms) of cargo to a 435-mile-high (700-kilometer) polar orbit, and the upgraded Vega-C will carry up to 4,850 pounds (2,200 kilograms) to the same orbit. The Vega-C’s first stage will be powered by the new P120C rocket motor, and the second stage will be a Zefiro 40 motor, replacing the smaller P80 and Zefiro 23 motors on the current Vega rocket.

The P120 rocket motors will also fly as strap-on boosters on the new Ariane 6 rocket, providing Avio a steady manufacturing cadence on its solid motor production line in Colleferro, Italy, which European officials view as critical to controlling costs on the Ariane 6 and Vega-C.

A Vega rocket launch costs between $35 million and $40 million, according to data published by the U.S. government. The Vega-C will cost the same, but carry heavier payloads into orbit, resulting in reduced prices on a per-pound basis.

“We have maintained as much commonality as possible, first and foremost, to transfer the same level of reliability we’ve had on Vega onto Vega-C,” Ranzo said. “The difference between Vega and Vega-C are the first two stages, the main stage and the second stage, even though these stages are essentially a scale up with respect to the ones we currently use on Vega. There is not a revolutionary change between Vega and Vega-C, it’s just a bigger first and second stage.

“At the same time, we are putting a much larger fairing on Vega-C, so that’s a big (improvement) in volume. So when you put it all together, it forced us to basically redesign the whole aerodynamics of the entire launcher, the mechanics, and a number of different things. I think the discussion we recently had with insurers clarified very well that … insurance companies see Vega as a good proxy of what they can estimate for the first few flights of Vega-C.”

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Giulio Ranzo. Become a member today and support our coverage.

The Vega rocket has found a niche in launching Earth observation satellites for European governments and foreign customers. With the first launch of a new multi-payload adapter structure later this year, Arianespace and Avio will try to gain a stronger foothold in the launch market for commercial nanosatellites, a market currently dominated by India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, Russia’s Soyuz rocket, and NanoRacks, which sells excess capacity on supply ships heading to the International Space Station.

Avio officials envision more Vega rocket variants in the 2020s, including a stripped-down rocket known as Vega Light, and a future design named Vega-E that would replace the upper two Vega stages with a single, restartable methane-fueled engine around 2024.

“Vega Light is essentially piggybacking on Vega-C,” Ranzo said. “The way we want to create a mini-rocket is just by eliminating the first stage of Vega-C, and what is left is pretty much the configuration of a mini-launcher, so we would likely adapt the current second stage of Vega-C to become the main stage of the Vega Light.”

By some counts, there are more than 100 dedicated smallsat launchers in development, but industry officials do not deem all of the concepts credible. Avio says the Vega Light could deliver around 660 pounds (300 kilograms) of cargo to low Earth orbit, which would place the new rocket squarely in the smallsat launch market.

“That’s pretty much what you hear from (Virgin Orbit’s) LauncherOne, the upper side of Rocket Lab’s Electron, but with one main difference. We’re building it upon something that has already flown, and as such, we piggyback on a number of things that we do not need to develop from scratch,” Ranzo said.

“Keeping commonality across the entire Vega family is what is driving the unit cost down,” Ranzo said. “We tend to want to manufacture only a few motor types, and through these few motor types, we can assemble them together differently to create a different offering to cover the different segments of the market, from the very small satellites, to the slightly bigger.”

While the Vega-E is part of a European Space Agency program, Avio is working on the Vega Light concept using private money. ESA is interested in seeding European companies to field smallsat launchers to compete with new providers like Rocket Lab and Virgin Orbit, but Ranzo said Avio is committed to Vega Light with or without public funding.

“In case we don’t get any ESA funding, we will continue funding it because we do see the business case,” he said. “It only represents a marginal investment for us vis-à-vis what we have already incurred for Vega-C.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.