A Chinese Long March 2D rocket successfully delivered seven satellites into a 300-mile-high (500-kilometer) orbit Friday, boosting international missions to measure seismic signals that could help predict future earthquakes, take detailed imagery of planet Earth and test compact camera, propulsion and radio technology.

The main payload carried aboard the two-stage Long March 2D rocket was Zhangheng 1, a Chinese-built satellite designed to sense precursor signals emitted before earthquakes, research that could eventually lead to quake predictions.

Nine scientific instruments aboard the 1,600-pound (730-kilogram) Zhangheng 1 spacecraft will measure Earth’s magnetic field, plasma and other particles to search for disturbances triggered in the early stages of underground seismic events.

Also known as the China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite, or CSES, the mission was developed in partnership between Chinese and Italian scientists from the China Earthquake Administration and the Italian Institute for Nuclear Physics.

The joint mission is part of a collaboration between the China National Space Administration and the Italian Space Agency, or ASI.

Named for Zhang Heng, an ancient Chinese scholar who pioneered earthquake detection, the Zhangheng 1 satellite will monitor Earth’s ionosphere, a region at the boundary between the atmosphere and space. Scientists will search for waves in the ionosphere’s plasma and magnetic field environment that could be linked to tremors and volcanic eruptions far below.

“Zhangheng 1 cannot be used to predict earthquakes directly, but it will help prepare the research and technologies for a ground-space earthquake monitoring and forecasting system in the future,” said Zhao Jian, a senior official at the China National Space Administration, in a report published by China’s state-run Xinhua news agency.

Zhangheng 1’s mission is expected to last five years.

“Zhangheng 1, with a wider coverage and better electromagnetic environment from space, will be an important supplement to earthquake monitoring in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and sea areas that cannot be fully covered by the ground observation network,” said Shen Xuhui, deputy chief designer of Zhangheng 1 and chief engineer of the Institute of Crustal Dynamics at the China Earthquake Administration, according to Xinhua.

Detecting weak disturbances in the ionosphere triggered by seismic activity requires highly-precise instrumentation.

One of Zhangheng 1’s largest science payloads, a high-energy particle detector, was developed by Italian scientists. Several other Chinese-built sensors were tested in a plasma chamber in Rome before their installation on the spacecraft.

Once in space, Zhangheng 1 was expected to deploy six instrument booms to a length of more than 13 feet, or 4 meters, to ensure the sensors are well away from magnetic field disturbances generated by the spacecraft itself. Engineers also designed the satellite to use components, such as titanium screws, to minimize their magnetic effects on Zhangheng 1’s sensitive instruments, Xinhua reported.

Italian officials nicknamed their part in the mission the “Limadou collaboration” for Matteo Ricci, a 16th century Italian missionary and explorer who traveled to China, where he was known as Li Madou.

In a statement released after Friday’s launch, the Italian space agency said the Zhangheng 1 mission will also aid in the study of solar physics and cosmic rays.

Six other satellites rode into orbit with Zhangheng 1 on a Chinese Long March 2D launcher.

The 134-foot-tall (41-meter) rocket lifted off at 0751 GMT (2:51 a.m. EST; 3:51 p.m. Beijing time) Friday from the Jiuquan space center in northwestern China’s Inner Mongolia region.

The rideshare launch opportunity was provided by China Great Wall Industry Corp., a government-owned company responsible for marketing Chinese launch services to commercial and international customers.

Approximately 12 minutes after launch, the satellites were placed into orbit around 500 kilometers (300 miles) above Earth on a track inclined 97.3 degrees to the equator.

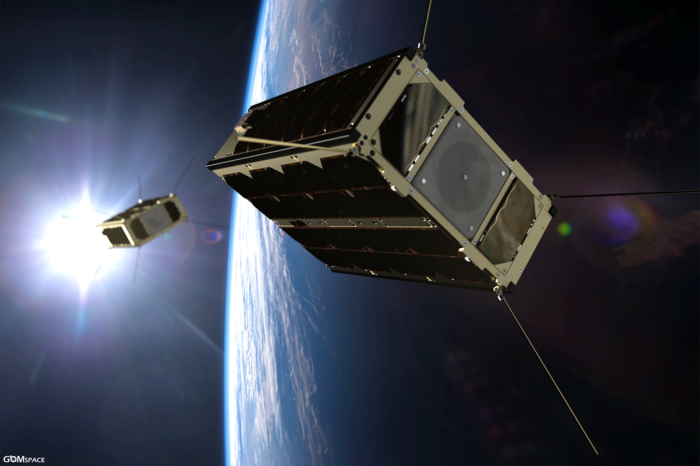

Two European CubeSats, each the size of a cereal box, were deployed by the Long March 2D’s upper stage. Named GomX-4A and GomX-4B, the satellites were built by GomSpace in Denmark.

GomX-4A will collect data for the Danish Ministry of Defense on airplane and ship movements over the Arctic region, and GomX-4B is an experimental nanosatellite funded by the European Space Agency.

The twin satellites will fly in long-distance formation — GomX-4B will do the maneuvering — at a range of up to 2,800 miles (4,500 kilometers) to test an S-band radio link between the craft. GomX-4B carries miniature cold-gas thrusters to guide its flight away from GomX-4A, along with a hyperspectral multi-color camera, a star tracker and components that will be checked to gauge their susceptibility to space radiation, according to ESA.

The GomX-4 satellites build on experience gathered on a predecessor nanosatellite named GomX-3 released from the International Space Station in 2015.

“Unlike GomX-3, GomX-4B will change its orbit using cold-gas thrusters, opening up the prospect of rapidly deploying future constellations and maintaining their separations, and flying nanosatellites in formations to perform new types of measurements from space,” said Roger Walker, head of ESA’s CubeSat program.

GomSpace said its ground team established contact with both satellites around six hours after their liftoff from China.

“The GomX-4B satellite is the most advanced satellite design we have initiated to date and we are very happy that ESA will participate in this project that will demonstrate possibilities of satellites flying in formation,” said Niels Buus, CEO of GomSpace. “We are very happy to work with ESA and together take the nanosatellite technology to a new level.

“Also, we look forward to working closely with (the Danish Ministry of Defense) on this exciting project and jointly develop and demonstrate the GomX-4A mission,” Buus said in a statement. “Our satellite and radio technologies are a perfect match for monitoring the vast and remote arctic area with the satellite flying over the scene every 90 minutes.”

The ÑuSat 4 and ÑuSat 5 microsatellites owned by Satellogic, an Argentine company, were also aboard the Long March 2D rocket launched Friday.

Nicknamed Ada and Maryam, the satellites were built in Montevideo, Uruguay, and each weighed around 80 pounds (37 kilograms). The ÑuSat 4 and ÑuSat 5 satellites join three others launched on two Chinese rocket missions in May 2016 and June 2017.

Satellogic confirmed the ÑuSat 4 and ÑuSat 5 satellites were alive in orbit after Friday’s launch.

Satellogic intends to deploy dozens, and potentially hundreds, of satellites in the next few years to collect high-resolution and hyperspectral imagery to aid urban planners, emergency responders, crop managers, and scientists tracking the effects of climate change.

The hyperspectral imager aboard each ÑuSat is tuned to measure the chemical composition of what it sees on Earth, helping identify pollutants, plants, building materials and other features.

Two CubeSats named FMN 1 and Shaonian Xing also launched Friday for Chinese start-up companies.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.