Ground crews took steps this week to prepare for the next Falcon 9 launch, set for no earlier than Jan. 30 with a telecom satellite for SES and the Luxembourg government, as SpaceX officials stressed their rocket was not to blame for the rumored loss of a mysterious U.S. government payload after liftoff Sunday.

The next satellite assigned to fly on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket has arrived at Cape Canaveral ahead of a planned Jan. 30 liftoff from pad 40 on a previously-flown SpaceX booster.

The launch window Jan. 30 opens at 4:23 p.m. EST (2123 GMT) and extends for 134 minutes.

Technicians will fuel the satellite, named GovSat 1, with hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide maneuvering propellant in the coming days, then close it up inside the Falcon 9’s clamshell-like payload fairing.

SES officials confirmed this week that satellite and rocket preps are on track for Jan. 30. A recycled Falcon 9 booster stage that first flew May 1 with the U.S. government’s classified NROL-76 payload will hoist the GovSat 1 spacecraft toward orbit, and a factory-fresh second stage will finish the job.

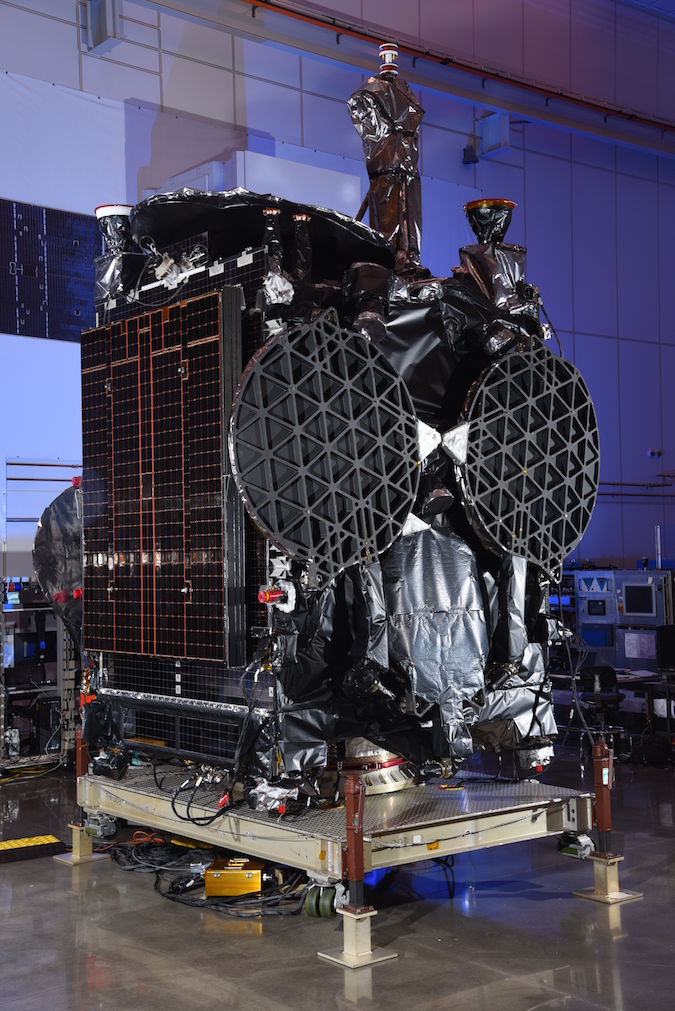

The GovSat 1 satellite, also known as SES 16, is owned by GovSat, a public-private joint venture between the government of Luxembourg and SES. Built by Orbital ATK in Dulles, Virginia, the spacecraft will head for geostationary orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator, where its military-grade X-band and Ka-band payload will support services from the Atlantic Ocean to the Middle East, including Europe, Africa, the Mediterranean Sea and the Baltic Sea.

“We are committed to our mission of providing secure satellite communication services for governments and institutions,” said Patrick Biewer, GovSat’s CEO. “GovSat 1, with its highly flexible payload featuring advanced encryption and anti-jamming capabilities, will further secure the connectivity for our users’ applications. We are incredibly excited about the upcoming launch of this satellite.”

GovSat will share the satellite’s communications capacity with Luxembourg’s NATO allies.

Few details on the fate of the Zuma mission were available Thursday, four days after the top secret payload lifted off on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral.

But numerous news reports, citing unnamed government sources, said the satellite apparently re-entered Earth’s atmosphere after failing to deploy from the Falcon 9’s second stage. If true, the spacecraft and rocket likely fell into the Indian Ocean, where the Falcon 9 second stage was to re-enter after releasing Zuma in orbit.

The U.S. military’s official catalog of human-made objects in space recorded an object that reached orbit attributed to Sunday’s Falcon 9 flight. The object was named USA-280 in the catalog and identified as a payload. The name is in line with the “USA” naming system used for spacecraft owned by the U.S. military and government intelligence agencies.

Quoting a military spokesperson, Bloomberg reported the U.S. government was not tracking any items in orbit from Sunday’s launch. The catalogued object dubbed USA-280 could have been in error, as occurred after a failed Landsat satellite launch in the 1990s, or the payload may no longer be in orbit, assuming it re-entered with the Falcon 9 upper stage within a few hours of launch.

Bloomberg also reported members of Congress have requested a classified briefing on the Zuma mission.

A network of amateur satellite trackers are on the lookout for Zuma in case it is still in orbit, but they are working off an estimate of its expected location, and it could take weeks to find the spacecraft, assuming it is still in space and is orbiting where predicted.

One of the most experienced trackers, an archaeologist named Marco Langbroek, shared an image taken by a Dutch pilot flying over Sudan around 2 hours and 15 minutes after the Falcon 9’s launch from Cape Canaveral.

Langbroek wrote in a blog post that he believes the image shows the Falcon 9’s upper stage dumping excess propellant after a de-orbit burn to drive it back into Earth’s atmosphere. The location and appearance of the sighting matched where the Falcon 9 and Zuma should have been orbiting, based on trackers’ pre-flight predictions, and was similar to fuel dumps observed after other launches.

This is the image taken by Dutch pilot Peter Horstink, from his aircraft over Khartoum near 3:15 UT, 2h 15m after launch.

This is probably the Falcon 9 venting fuel.#Zuma pic.twitter.com/EEsl7e1sQP— Dr Marco Langbroek (@Marco_Langbroek) January 8, 2018

What was not clear was whether Zuma was still attached to the Falcon 9 second stage at the time of the pilot’s observation. If so, it likely fell back to Earth with the rocket, which carried out pre-programmed instructions and was unable to receive new commands from the ground.

SpaceX officials said the Falcon 9 functioned as expected during Sunday’s launch.

“For clarity: after review of all data to date, Falcon 9 did everything correctly on Sunday night,” said Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and chief operating officer. “If we or others find otherwise based on further review, we will report it immediately. Information published that is contrary to this statement is categorically false. Due to the classified nature of the payload, no further comment is possible.”

She said work to ready SpaceX’s next launches remained on schedule, with the first hold-down firing of the company’s new Falcon Heavy rocket planned this week at Kennedy Space Center’s pad 39A.

“Since the data reviewed so far indicates that no design, operational or other changes are needed, we do not anticipate any impact on the upcoming launch schedule,” she said. “Falcon Heavy has been rolled out to launch pad LC-39A for a static fire later this week, to be followed shortly thereafter by its maiden flight. We are also preparing for an F9 launch for SES and the Luxembourg government from SLC-40 in three weeks.”

A launch date for the maiden Falcon Heavy test flight has not been officially scheduled, but it could occur by the end of January.

Shotwell’s statement emailed to reporters was an unusual one for SpaceX, which rarely comments on planned Falcon 9 flights before the week of launch. The company also rarely releases formal statements on the outcome of each launch.

The Zuma payload was built for the government by Northrop Grumman. A spokesperson for the huge defense contractor declined to comment on Zuma after Sunday night’s launch.

“This is a classified mission,” wrote Lon Rains, a Northrop Grumman spokesman, in an email to Spaceflight Now. “We cannot comment on classified missions.”

Reporters Sunday night expected confirmation from Northrop Grumman after officials confirmed the Zuma payload’s successful launch, but the announcement never came.

The purpose of Zuma’s mission was never disclosed, and no government or military agency claimed ownership. A spokesperson for National Reconnaissance Office, which owns the U.S. government’s spy satellite fleet, said Zuma did not belong to that organization.

The NRO and military agencies typically acknowledge their ownership of clandestine satellites, even if details about their missions remain under a shroud of secrecy.

According to Wired Magazine, Northrop Grumman supplied the adapter fitting connecting the Zuma payload with the Falcon 9 rocket. The attachment fixture is normally included in the launch service purchased by the payload’s owner.

If the separation system was to blame for Zuma’s rumored demise, the malfunction could have been under the responsibility of Northrop Grumman, not SpaceX.

But with the mission’s classified nature, confirmation of Zuma’s fate, and what may have gone wrong, remained elusive.

On the heels of the Falcon Heavy and Falcon 9/GovSat 1 missions later this month, SpaceX plans at least two launches in February for two Spanish customers.

A Falcon 9 rocket is set to lift off in February from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California with the Spanish-owned Paz radar imaging satellite, and another Falcon 9 is slated to haul the Hispasat 30W-6 geostationary communications craft to orbit from Cape Canaveral some time in February.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.