Updated March 9 with OneWeb agreement.

Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos revealed new details of his space company’s reusable orbital-class booster Tuesday, releasing an animation illustrating the rocket’s liftoff from Cape Canaveral and announcing a contract with Eutelsat to put a commercial communications satellite on one of the launcher’s first missions.

Speaking at the Satellite 2017 industry conference in Washington, Bezos said Blue Origin’s towering New Glenn rocket, named for pioneering astronaut John Glenn, could launch by 2020 and be reused up to 100 times.

Paris-based Eutelsat, one of the largest satellite telecom operators in the world, has signed up as the first paying customer for a New Glenn launch in 2021 or 2022.

“Eutelsat is one of the world’s most experienced and innovative satellite operators, and we are honored that they chose Blue Origin and our New Glenn orbital launch vehicle,” Bezos said in a statement.

“Eutelsat has launched satellites on many new vehicles and shares both our methodical approach to engineering and our passion for driving down the cost of access to space,” Bezos said. “Welcome to the launch manifest, Eutelsat, can’t wait to fly together.”

One day later, OneWeb and Blue Origin unveiled an agreement for at least five New Glenn launches with multiple broadband Internet satellites in the early 2020s, part of OneWeb’s planned low Earth orbit fleet comprising nearly 900 spacecraft.

The New Glenn’s primary base will be at Cape Canaveral, where Blue Origin is constructing a cavernous rocket factory just outside the gates of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Blue Origin has started preliminary earthmoving work for a launch pad at Complex 36, a former Atlas rocket facility at nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, and plans to install an engine test stand at neighboring Complex 11.

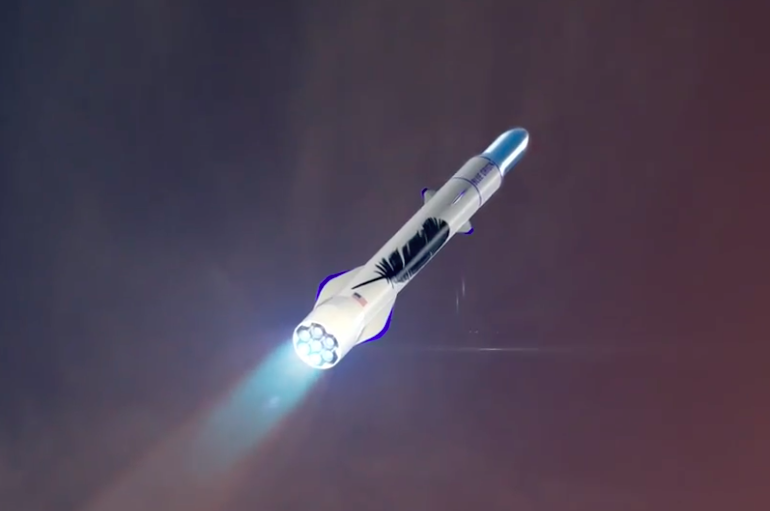

The animation released by Blue Origin on Tuesday shows the New Glenn rocket taking off from Complex 36 on the power of seven BE-4 main engines, burning a mixture of liquefied natural gas and liquid oxygen. The engines each produce about 550,000 pounds of thrust at full throttle, combining to generate 3.85 million pounds of thrust at liftoff.

The first stage engines will give way to a single modified BE-4 engine on the New Glenn’s second stage to deliver satellites, and eventually crews, into orbit, while the booster flips around and reignites to slow its descent toward a barge positioned offshore in the Atlantic Ocean, according to Blue Origin.

The New Glenn first stage will have aerodynamic fins, or strakes, for improved steering and extend six landing legs just before touchdown.

The recovery maneuver is familiar to industry officials and space enthusiasts, bearing similarity to the landings pioneered by rival SpaceX.

Blue Origin held a patent on its plans to land rocket boosters on ships in the ocean using rocket thrust to slow the vehicles down for landing, but SpaceX disputed the validity of the patent claims by pointing to academic papers and proposals dating back decades outlining concepts to recover rockets on ocean-going vessels for refurbishment and reuse.

Blue Origin in 2015 canceled the claims disputed by SpaceX, which achieved its first rocket landing at sea in April 2016.

Excited to announce we have signed our 1st #NewGlenn customer. Welcome to the launch manifest @Eutelsat_SA pic.twitter.com/fTeKKneYnJ

— Jeff Bezos (@JeffBezos) March 7, 2017

The two-stage New Glenn variant, shown in the animation, will stand 270 feet (82 meters) tall and haul nearly 29,000 pounds, or 13 metric tons, to geostationary transfer orbit, the drop-off point for most communications satellites, like the platforms owned and operated by Eutelsat. The rocket’s payload capacity to low Earth orbit, a few hundred miles in altitude, will be nearly 100,000 pounds, or 45 metric tons, Bezos said.

With the addition of an optional third stage for deep space missions, the New Glenn’s height will increase to 313 feet (95 meters).

Blue Origin’s BE-4 engine in development to power the New Glenn rocket is scheduled to perform its full-scale hotfire test later this year at the company’s remote West Texas test site.

Bezos tweeted two pictures of the first fully-assembled BE-4 engine Monday, adding that the second and third copies are “following close behind.”

United Launch Alliance has tapped the BE-4 engine as its preferred powerplant for the next-generation Vulcan rocket scheduled for a maiden launch in 2019. ULA is paying Aerojet Rocketdyne, a traditional engine-builder, to continue developing its kerosene-fueled AR1 engine as a backup option.

“We are very close to selecting,” said Tory Bruno, president and CEO of ULA, in a Feb. 16 presentation at the University of Texas at El Paso. “And if the testing that happens in the next couple of months is successful, we’ll probably end up on that Blue Origin (engine).”

The BE-4 and AR1 will employ a staged combustion cycle, a more efficient engine cycle than currently available on other U.S. liquid hydrocarbon rocket engines. Staged combustion engines currently flying include the Russian RD-180 on ULA’s Atlas 5, which the Vulcan will replace.

It’ll be very exciting because it’ll bring that advanced Russian engine cycle technology to America, and it will make it much much better because this engine will be additively manufactured,” Bruno said. “It will be much more produceable. It will be much lighter, and it will be much much more affordable.”

Blue Origin’s first production engine, the BE-3, burns liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen and flies on the company’s suborbital New Shepard rocket. The New Shepard has launched successfully six times, including five straight vertical liftoffs and landings with the same reusable single-stage booster in 2015 and 2016.

Eutelsat has taken chances on new rockets before, placing its satellites on the inaugural launches of the Atlas 3, Atlas 5, Delta 4 and Ariane 5 ECA boosters in the early 2000s.

In a statement Tuesday, Eutelsat said the contract with Blue Origin “reflects Eutelsat’s longstanding strategy to source launch services from multiple agencies in order to secure access to space.”

Eutelsat said the New Glenn launcher will be compatible with “virtually all” of its satellites, allowing the company to assign a spacecraft to the mission 12 months ahead of time.

“Blue Origin has been forthcoming with Eutelsat on its strategy and convinced us they have the right mindset to compete in the launch service industry,” said Rodolphe Belmer, CEO of Eutelsat. “Their solid engineering approach, and their policy to develop technologies that will form the base of a broad generation of launchers, corresponds to what we expect from our industrial partners.

“In including New Glenn in our manifest, we are pursuing our longstanding strategy of innovation that drives down the cost of access to space and drives up performance,” Belmer said in a statement. “This can only be good news for the profitability and sustainability of our industry.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.