Tech pioneer and entrepreneur Jeff Bezos said this week his growing launch company, Blue Origin, plans to debut a 30-story satellite booster built and launched from Florida by the end of the decade.

In an update emailed to media and Blue Origin followers Monday, Bezos wrote that the launcher is a “very important step” toward the company’s vision of “millions of people living and working in space.”

The “New Glenn” rocket will come in two variants — two-stage and three-stage configurations — and blast off from Complex 36 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, a facility leased by Blue Origin from Space Florida, a state-owned economic development agency which arranges commercial agreements to take over disused facilities on the Space Coast.

Large-scale construction of Blue Origin’s rocket factory just outside the security gate of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center began earlier this year. Crews are currently excavating the site for the foundation of the sprawling new factory.

At Complex 36, Blue Origin plans to build a launch pad on the site that formerly served as the base for 145 Atlas launches from 1962 through 2005. The company also wants to build at adjoining Complex 11 on Cape Canaveral’s famed “missile row,” which last hosted a space launch in 1964.

The New Glenn is named for Mercury astronaut John Glenn, the first American to reach Earth orbit.

The launcher’s first stage will be powered by seven BE-4 rocket engines burning a mixture of liquefied natural gas and liquid oxygen. The engines each produce about 550,000 pounds of thrust at full throttle, combining to generate 3.85 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, according to Bezos.

The BE-4 engine is also the No. 1 option under consideration by United Launch Alliance, a 50-50 joint venture owned by Boeing and Lockheed Martin, as the main engine for its new Vulcan booster. A full-scale hotfire test of the BE-4 engine is slated to occur late this year or in early 2017 at Blue Origin’s test site in West Texas.

ULA chief executive Tory Bruno said last week his engineering team is awaiting the full-scale hotfire test before making a final decision on the BE-4 engine. If selected, two of the BE-4 engines would be fixed to the base of the Vulcan first stage, with solid rocket boosters around the rocket for additional thrust, as required by each mission.

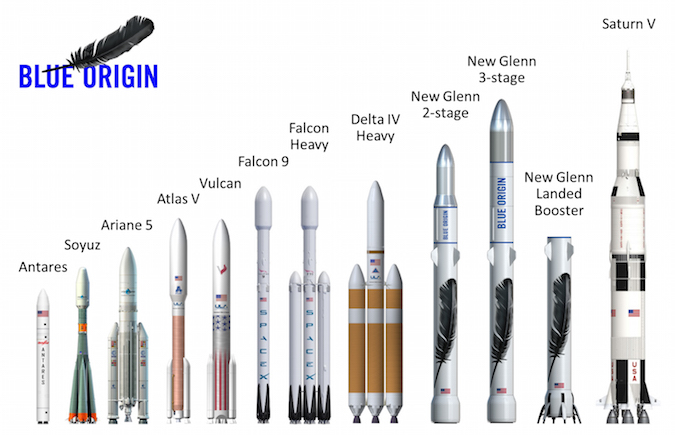

The New Glenn rocket detailed by Bezos and illustrated in a rocket lineup released by Blue Origin will not have strap-on boosters.

Bezos wrote the rocket’s second stage will have single “vacuum-optimized” BE-4 engine. Blue Origin can add an optional third stage powered by a hydrogen-fueled BE-3 engine, which can throttle up to about 110,000 pounds of thrust at full power.

The privately-developed rocket could launch a range of commercial satellites and military payloads once certified by the U.S. Defense Department. Human passengers are also planned.

“We plan to fly New Glenn for the first time before the end of this decade from historic Launch Complex 36 at Cape Canaveral, Florida,” Bezos wrote. “New Glenn is designed to launch commercial satellites and to fly humans into space. The 3-stage variant – with its high specific impulse hydrogen upper stage – is capable of flying demanding beyond-LEO (Low Earth Orbit) missions.”

The two-stage version of New Glenn will stand 270 feet (82 meters) tall, and the three-stage rocket will tower 313 feet (95 meters), making it one of the tallest launchers ever built, just shy of the height of the Saturn 5 moon rocket and NASA’s Space Launch System.

Bezos did not disclose the targeted cost and payload capacity of the New Glenn.

The New Glenn’s 23-foot-diameter (7-meter) first stage will be recovered — likely on a barge positioned offshore in the Atlantic Ocean — and reused in similar manner to the rocket recovery scheme pioneered by SpaceX.

Blue Origin held a patent on its plans to land rocket boosters on ships in the ocean using rocket thrust to slow the vehicles down for landing, but SpaceX disputed the validity of the patent claims by pointing to academic papers and proposals dating back decades outlining concepts to recover rockets on ocean-going vessels for refurbishment and reuse.

Blue Origin last year canceled the claims disputed by SpaceX, which achieved its first rocket landing at sea in April.

The New Glenn is Blue Origin’s second major launcher development, coming after the smaller New Shepard booster sized for suborbital flights. Keeping with Blue Origin’s naming theme, the New Shepard is named for Alan Shepard, the first American to fly in space on a suborbital jaunt in 1961.

The single-stage New Shepard is already flying with the BE-3 engine, and the rocket has completed five test flights — the last four with the same reusable vehicle.

Blue Origin plans its next New Shepard test flight in the “first part of October,” Bezos said, when the booster and its unoccupied crew capsule will conduct an in-flight abort test at 16,000 feet to demonstrate the rocket’s safety system can save astronauts and space tourists from a launch failure.

The dramatic test will likely destroy the New Shepard booster, which is not designed to survive the forces associated with the abort maneuver after liftoff. The capsule will escape the vicinity of the rocket, then deploy parachutes to descend back to the ground at Bezos’ remote test site near Van Horn, Texas.

Like the last New Shepard test flight in June, Blue Origin plans to webcast the in-flight abort, according to Bezos.

The safety demo is a key test before Blue Origin adds test pilots to future New Shepard launches. The company eventually eyes flying researchers and space tourists aboard the crew capsule for brief trips above 62 miles (100 kilometers), the internationally recognized boundary of space.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.