Japan’s space agency says it has ceased efforts to rescue a failed X-ray astronomy satellite after it spun out of control and broke apart in orbit, declaring the nearly $400 million mission lost two months after its launch.

Controllers on the ground lost contact with the Hitomi mission March 26 after a series of attitude control failures caused the satellite spin up and shed critical segments of its solar panels, according to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency.

Officials said Thursday that signals thought to be from the Hitomi spacecraft, also known as Astro-H, received by ground controllers after the satellite’s March 26 failure turned out not to be from the observatory.

“JAXA has also received information from several overseas organizations that indicated the separation of the two solar array paddles from Astro-H,” the agency said in a statement. “Considering this information, we have determined that we cannot restore the Astro-H’s functions.”

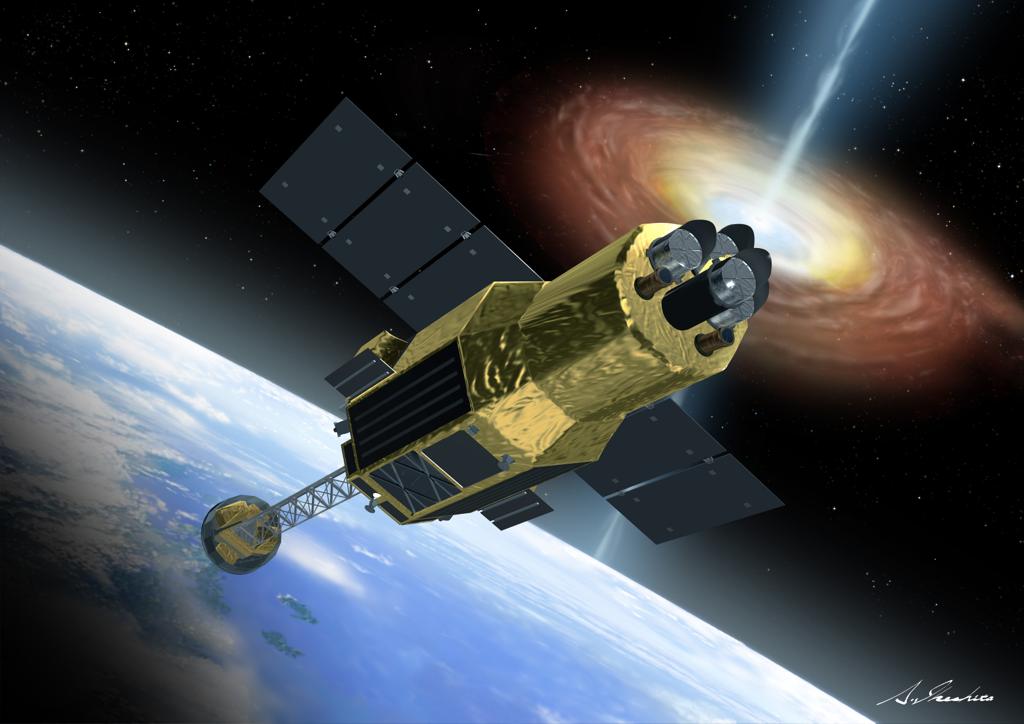

The Hitomi X-ray observatory launched Feb. 17 on a mission designed to last at least three years.

Its objectives included studying black holes and giant galactic clusters, the largest structures in the universe.

JAXA said engineers will now determine the cause of the mission’s premature failure.

“We will carefully review all phases from design, manufacturing, verification, and operations to identify the causes that may have led to this anomaly including background factors,” JAXA said in a statement.

Described by scientists as the flagship X-ray astronomy project of the decade, Hitomi carried a suite of instruments sensitive to a wide range of energies on the electromagnetic spectrum, from so-called “soft” X-rays around 300 electron volts to “soft” gamma rays up to 600,000 electron volts. For comparison, visible light photons are measured around 2 or 3 electron volts.

Such high-energy light beams do not penetrate Earth’s atmosphere, meaning the X-ray universe is only observable by sending a satellite into orbit. X-ray telescopes allow observations of black holes, which form in the aftermath of violent supernova explosions, and large-scale structures of the universe.

Formed by the powerful supernova explosions of old stars, black holes give off X-rays as they ingest matter, sending emissions through the universe that can only be detected by telescopes like the sensors aboard Hitomi.

Hitomi carried a NASA-developed X-ray spectrometer to measure the composition and velocity of super-heated matter surround black holes. Astronomers expected the detector to send back unrivaled data about the complicated environment around the compact skeletons of stars.

The core of the X-ray spectrometer was a “microcalorimeter” unlike any successfully flown before. The researchers in charge of the instrument tried to fly it on a mission that eventually became NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, but officials kept the spectrometer off Chandra due to budget concerns.

NASA partnered with Japan to launch the instrument on an X-ray observatory in 2000, but that mission was lost in a launch mishap. Japan’s follow-up X-ray telescope launched with a replacement NASA-built spectrometer in 2005, but the sensor failed before collecting science data.

The science team behind microcalorimeter technology now has to contend with another failure.

The cutting edge instrument was able to take measurements of Crab Nebula and the Perseus galaxy cluster before Hitomi went silent last month.

Chandra is the workhorse for astronomers pursuing research in those areas. Europe’s XMM-Newton space telescope is also an asset for X-ray astronomers. But both missions launched in 1999 and are functioning well beyond their designed lifetimes.

The NuSTAR X-ray telescope developed by NASA is also available, but its sensor is not as capable as the instruments lost aboard Hitomi.

Scientists may have to wait for the next large X-ray mission on the books. The European Space Agency-led Athena X-ray observatory is expected to launch in 2028.

“JAXA expresses the deepest regret for the fact that we had to discontinue the operations of Astro-H and extends our most sincere apologies to everyone who has supported Astro-H, believing in the excellent results Astro-H would bring, to all overseas and domestic partners, including NASA, and to all foreign and Japanese astrophysicists who were planning to use the observational results from Astro-H for their studies,” the agency said in a statement.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.