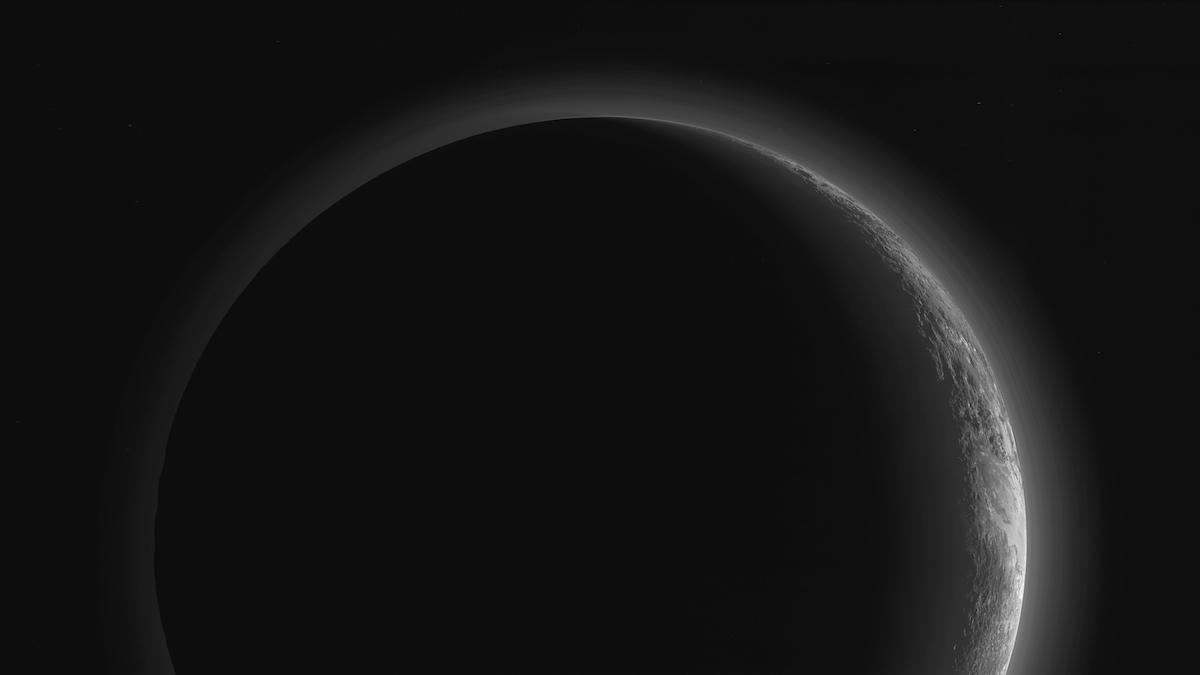

An image released Thursday, taken by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft minutes after zipping past Pluto in July, shows the backlit world on a new scale, revealing rugged mountains, glacial plains and deep layers of atmospheric haze.

It is an expanded version of a crescent view first released in September, according to NASA, showing an entire hemisphere of Pluto with silhouetted terrain on the night side of the dwarf planet at the left side of the image. Scientists also say the subtle shadow cast by Pluto on its tenuous atmosphere is visible near the top of the picture.

Alan Stern, the New Horizons mission’s principal investigator, called the picture “mouthwatering” on Twitter.

BLOW THIS UP—On ur screen that is! Welcome to Pluto! https://t.co/k83nUqNJTZ #UnFREAKINbeliveable #Mouthwatering pic.twitter.com/lWe1vo1YUj

— AlanStern (@AlanStern) October 29, 2015

NASA says the picture was taken when New Horizons was 11,000 miles (18,000 kilometers) from Pluto.

On the right side of the image, the vast glacial plains of Sputnik Planum are seen bordering ranges of 11,000-foot (3,500-meter) mountains dubbed Norgay Montes and Hillary Montes, after the climbing duo who first reached the summit of Mount Everest in 1953.

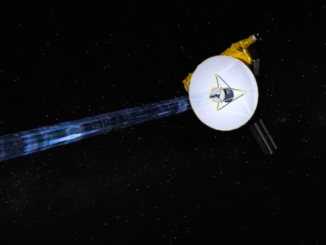

New Horizons is slowly beaming data recorded at Pluto back to Earth. Now traveling more than 3 billion miles away, the bandwidth of the spacecraft’s fixed communications antenna is limited, and all the data will not be in the hands of scientists until some time next year.

The spacecraft is also returning images captured on the probe’s final approach to Pluto, showing regions not seen up-close during the July 14 flyby.

Meanwhile, New Horizons has completed three course correction burns to budge its trajectory toward a small Kuiper Belt Object for a planned encounter Jan. 1, 2019. A fourth maneuver in the series is scheduled for Nov. 4 to finish aiming the spacecraft toward its next target.

But NASA still must approve the New Horizons team’s plan to fly past a second destination in the Kuiper Belt, a ring of mini-worlds circling the sun beyond the orbit of Neptune, of which Pluto is the largest object. The space agency granted preliminary approval for New Horizons to change its course for the 2019 fly opportunity.

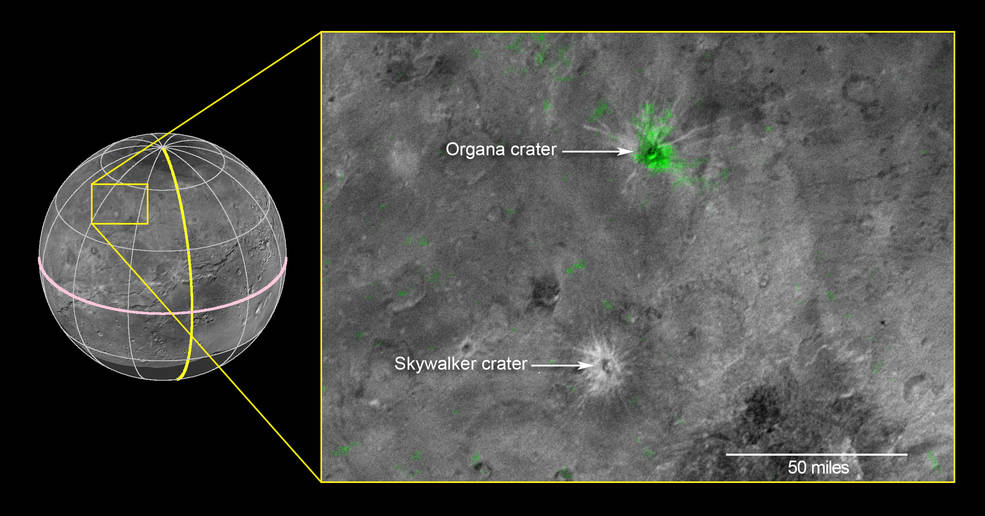

Researchers also announced a new discovery on Pluto’s moon Charon that may help scientists understand its enigmatic history.

An infrared spectral scan of a fresh crater named Organa on Charon’s Pluto-facing hemisphere revealed high levels of ammonia. A nearby crater with a similar appearance mysteriously has no ammonia signature.

Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

“Why are these two similar-looking and similar-sized craters, so near to each other, so compositionally distinct?” asked Will Grundy, New Horizons composition team lead from Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. “We have various ideas when it comes to the ammonia in Organa. The crater could be younger, or perhaps the impact that created it hit a pocket of ammonia-rich subsurface ice. Alternatively, maybe Organa’s impactor delivered its own ammonia.”

Geologists are trying to piece together what the ammonia detection means. It could be a window into a more active history of cryovolcanism on Charon, when the moon’s surface may have been repaved through eruptions of liquids kept warm by the body’s internal heating.

“This is a fantastic discovery,” said Bill McKinnon, deputy lead for the New Horizons geology, geophysics and imaging team from Washington University in St. Louis. “Concentrated ammonia is a powerful antifreeze on icy worlds, and if the ammonia really is from Charon’s interior, it could help explain the formation of Charon’s surface by cryovolcanism, via the eruption of cold, ammonia-water magmas.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.