The first piloted flight of NASA’s Orion space capsule, a vehicle designed to carry astronauts away from Earth for the first time in two generations, may slip from 2021 to 2023, agency officials said Wednesday.

A thorough review of the program in recent weeks highlighted risks that threaten the crewed flight’s target launch date in August 2021, and managers concluded the mission is likely to fly some time later.

NASA officials set April 2023 as the timeframe when they expect the Orion spacecraft to be ready to host humans on a flight around the moon.

“The team is going to continue to work toward the August 2021 date, but we’re committing that we’ll be no later than April 2023,” said Robert Lightfoot, NASA’s associate administrator. “I saw no reason this early in the process to change that ‘working to’ date for the team, and neither did the standing review board.”

Lightfoot said an April 2023 launch for the first Orion mission with astronauts is achievable with 70 percent confidence, keeping with NASA’s policy.

NASA did not run models to calculate a confidence level for the flight’s target launch date in 2021, but “it’s not a very high confidence level, I’ll tell you that, just because of the things we see historically pop up,” Lightfoot said.

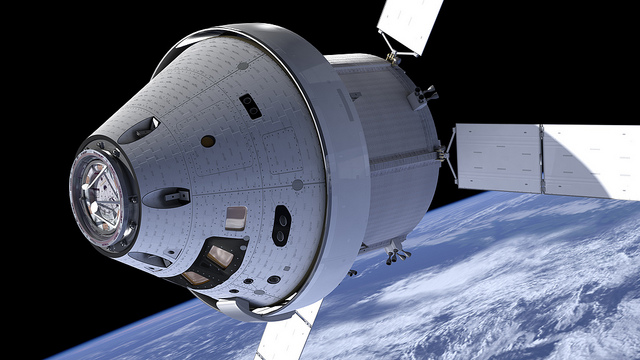

The Orion spacecraft, designed to host four astronauts for up to 21 days in deep space, will blast off on top of NASA’s Space Launch System, a huge rocket in development borrowing propulsion and technologies from the retired space shuttle program.

A test flight of the heavy-lift launcher and the Orion capsule without a crew, called Exploration Mission-1, remains on track for late 2018, Lightfoot said, but will undergo another review later this year. The Exploration Mission-2 flight, now targeted for no later than April 2023, is the program’s first space shot with astronauts aboard.

The Orion program’s confirmation review, held at NASA Headquarters in Washington with participation from an independent board, also set a budget to take the spacecraft through its first piloted mission.

NASA says it needs another $6.77 billion to complete development of Orion through 2023, atop $10.5 billion spent on the spacecraft since the project dawned with the Constellation program, an initiative started in 2005 under the Bush administration.

That brings the program’s total projected cost to more than $17 billion through the first flight with astronauts. The Space Launch System budget is forecast to be more than $7 billion from early 2014 through the first demonstration launch in 2018.

Bill Gerstenmaier, head of NASA’s directorate responsible for human exploration and operations, said the Orion project is making “solid technical progress” after a successful orbital test flight in December 2014.

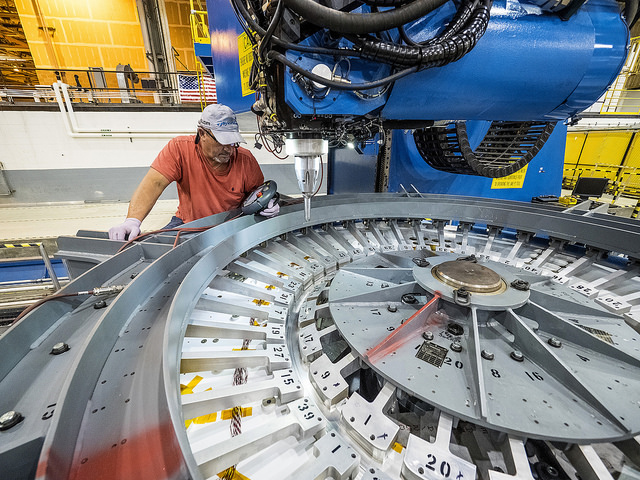

Technicians at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans have started welding the pressure shell for the next Orion vehicle, which will fly in 2018 on its next uncrewed test flight. NASA will deliver the capsule’s basic structure to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida early next year for final assembly, outfitting and testing.

Reviewers charged with measuring the progress of the Orion program raised concerns about NASA’s plans to reuse hardware on multiple flights of the capsule, software development efforts, and structural testing, officials said.

NASA and Lockheed Martin, the agency’s prime contractor for Orion, plan to take key avionics boxes from the EM-1 Orion capsule and reuse them for EM-2.

“The intent right now is to refly those boxes on EM-2,” Gerstenmaier said. “The concern is if you have any kind of problem with the box on EM-1, and it’s not available for EM-2, you could run into a problem where that impacts the build of EM-2.”

Lockheed Martin is currently under contract to deliver three complete Orion crew capsules, including the vehicle flown on the EFT-1 demo flight in 2014 and spacecraft for EM-1 and EM-2.

“Right now, we’re not seeing any issues in those areas, but we have to account for those because we’ve got a lot of runway in front of us,” Lightfoot said.

“I think we’re being somewhat conservative,” Gerstenmaier said in a conference call with reporters Wednesday. “My teams will tell you that they’re trying to retire every risk out there.”

“Each times these guys hit a milestone in their testing and their predictions, we either retire risk or actually realize it,” Lightfoot told reporters.

Gerstenmaier gave high marks to engineers working on a redesign of Orion’s heat shield. Instead of installing the thermal shell on to the capsule in one monolithic piece, technicians will bolt on the Avcoat ablative heat shield in blocks for future flights.

It is a lesson learned by engineers after it took ground crews longer than planned to fabricate and install the heat shield for the EFT-1 test flight last year, in which a Delta 4-Heavy rocket lofted the capsule on a trajectory 3,600 miles above Earth in a major test of the craft’s thermal protection system and guidance, navigation and control algorithms.

“We are making a heat shield change, but the engineering test article for that heat shield is already going to be complete by the end of this month, so that’s moving at a very good pace moving forward,” Gerstenmaier said.

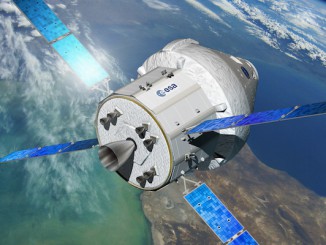

Another potential problem area identified by the review board involved the European-built service module for Orion. NASA cinched an agreement with the European Space Agency in early 2013 to supply the power and propulsion unit for the EM-1 robotic test flight in 2018.

ESA and its service module contractor, Airbus Defense and Space, are working on the component with technologies derived from Europe’s Automated Transfer Vehicle, which made five successful supply deliveries to the International Space Station before its retirement earlier this year.

The service module’s schedule is at the top of the list of threats that could delay the EM-1 test flight in 2018, according to Bill Hill, NASA’s deputy associate administrator for exploration systems.

But the concerns coming out of the Orion confirmation review focused on NASA’s plans for the service module for EM-2. NASA and ESA have not agreed on whether Europe will contribute a full-up service module for Orion’s first crewed mission.

“We’ve got the first (European service module) coming in for EM-1, and what we learn from EM-1 actually feeds into what happens for EM-2,” Lightfoot said.

The Exploration Mission-1 flight plan calls for the Orion module and its four-person crew to go into a distant retrograde orbit about 44,000 miles from the moon for a mission lasting up to three weeks.

“We use EM-1 to check out the service module to make sure we can do the burns in and and out of the distrant retrograde orbit around the moon,” Gerstenmaier said. “We’ll make sure the communications systems work, we’ll make sure the navigation stuff works, (and) we’ll make sure all the software works.

“Then comes EM-2, and the big thing there is the crew interfaces,” Gerstenmaier said. “How does the crew interact with the vehicle? What are the displays and controls like? What do they do during entry configuration?”

EM-2 also introduces Orion’s life support systems, such as oxygen supplies, devices to scrub carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, plus temperature and humidity controls, according to Gerstenmaier.

It is unlikely the EM-2 crew will rendezvous with an asteroid as part of NASA’s asteroid retrieval mission, an initiative to send out a robotic space probe to tow a small rock back into lunar orbit for human visits, according to Gerstenmaier. That mission, if approved by Congress, will come later.

Gerstenmaier said NASA plans to launch an SLS/Orion mission once per year after EM-2, assuming budgets allow. Later missions in a region around the moon dubbed “cis-lunar space” may test out rendezvous techniques, spacewalks, asteroid docking, and in-space habitats to prove out technologies required for Mars missions.

“It’s important to note that we are building a big program,” Lightfoot said. “We’re building a multi-decadal human exploration program, and while the individual launches of EM-1 and EM-2 are very important, and they are great indicators of our progress and how we’re doing, we’ve got to balance those individual missions with the overall context of this exploration journey we’re on.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.