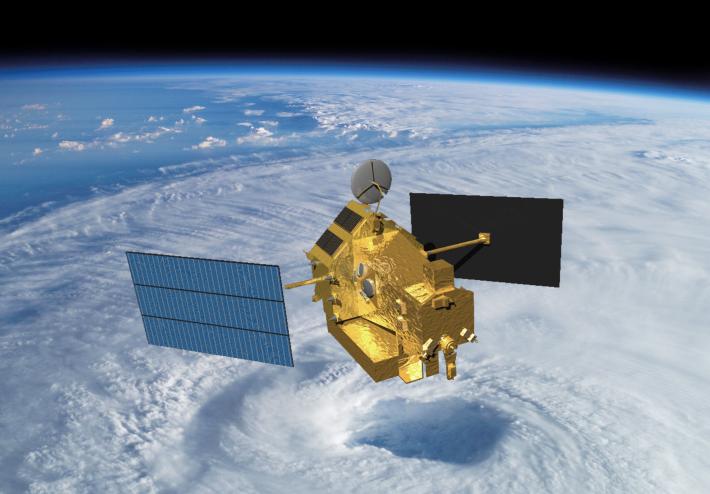

NASA has switched off research instruments aboard the long-lived Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, preparing the satellite for a destructive re-entry as soon as June and ending its 17-year run observing tropical cyclones from orbit.

The TRMM satellite ran out of fuel last year and began an uncontrolled descent from an orbit 400 kilometers, or 250 miles, above Earth. Officials kept the craft’s two instruments intermittently running until TRMM reached a predetermined altitude.

The mission’s primary sensor, a precipitation radar, was switched off for the final time April 1, according to Steve Cole, a NASA spokesperson.

Officials planned to keep TRMM’s other instrument, a microwave imager, operating a bit longer. The satellite’s final scientific sensors were due to be deactivated Wednesday, said Michael Freilich, head of NASA’s Earth science division.

TRMM’s orbit reached an average altitude of about 333 kilometers, or 206 miles, as of Wednesday.

“This has been a long mission,” Freilich said Monday in a presentation to the NASA Advisory Council’s science committee. “TRMM has been flying since November 1997.”

TRMM launched Nov. 27, 1997, aboard a Japanese H-2 rocket from the Tanegashima Space Center in Japan. Its mission was originally supposed to last three years.

The project is jointly managed by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. NASA was responsible for construction of the satellite and daily operations, and JAXA supplied the mission’s radar instrument and the launcher.

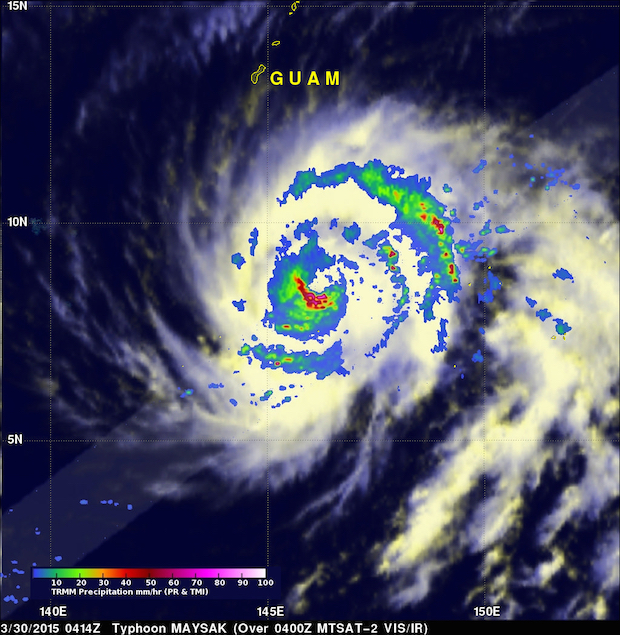

“TRMM has been the world’s foremost satellite for the study of precipitation and climate processes in the tropics, and an invaluable resource for tropical cyclone research and operations,” said Scott Braun, TRMM’s project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

The $650 million satellite’s radar is the first of its kind ever flown in space, yielding unprecedented 3D views into tropical cyclones and storms in a belt near the equator. TRMM data helped forecasters at the National Hurricane Center predict tropical storm intensification.

“TRMM data provided the most accurate estimate ever of tropical rainfall and lightning and its variations,” mission managers wrote in a notice to scientists on a NASA website. “It led to new insights into the structure and evolution of convective systems, including extreme events like tropical cyclones and flood producing storms. TRMM provided a benchmark climatology used to validate and improve global climate and weather forecast models and shed light on ways in which humans impact precipitation.”

NASA and JAXA launched a follow-on observatory last year named the Global Precipitation Measurement mission. The GPM satellite flies in a different orbit than TRMM, covering a wider swath of Earth from the tropics nearly to the poles to expand precipitation research to include winter weather.

The new mission’s upgraded instruments also detect lighter precipitation than TRMM, feeding data into long-range climate models and short-term weather forecasts.

Freilich said TRMM is on pace to re-enter the atmosphere as soon as mid-June, up to a year sooner than officials predicted when TRMM ran out of propellant in July 2014. The satellite is succumbing to the minuscule amount of drag present in low Earth orbit, and TRMM’s rate of descent will increase as it nears re-entry.

TRMM retained a small quantity of fuel to maneuver out of the way of space junk during the descent, a safety feature designed to avoid a collision that would litter orbital pathways with more debris and endanger other satellites.

TRMM could fall anywhere between 35 degrees north and south latitude. Most of the craft will burn up, but experts expect some fragments will survive to Earth’s surface.

A decision made in 2005 by then-NASA Administrator Mike Griffin to extend TRMM’s operations meant the mission would consume propellant originally set aside to lower the spacecraft’s orbit for disposal over a remote stretch of the uninhabited South Pacific Ocean.

Griffin’s decision came after a report by a National Research Council panel recommended that NASA abandon plans to end the mission in time to ensure the satellite’s re-entry could be steered away from populated areas.

A risk review conducted by NASA in 2002 put the probability of a human injury or death caused by TRMM’s uncontrolled re-entry at 1-in-5,000, about twice the casualty risk deemed acceptable for re-entering NASA satellites.

The review said the additional risk of an uncontrolled re-entry could be “tolerated in return for other (public safety) benefits.”

Griffin and scientists agreed, concluding that data collected by TRMM could aid in forecasting tropical cyclones, improving intensity predictions and potentially saving lives.

The casualty risk from TRMM’s re-entry is lower than other recent unguided satellite re-entries, such as the fall of NASA’s Upper Atmospheric Research Satellite and a German X-ray astronomy satellite in 2011.

The re-entry of the European Space Agency’s GOCE gravity mapping satellite in 2013 posed a lower risk than TRMM.

Without fuel, the TRMM satellite has a mass of 2,621 kilograms, or 5,778 pounds.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.